'Pleas and Petitions': Southern Colorado’s historic struggle for representation

DENVER — Forgotten Southern Colorado isn’t just a Facebook community dedicated to the legacy of the state’s earliest settlements. It’s also a sentiment — and historically, a legislative reality.

In 1861, 13 years after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Southern Colorado petitioned heartily to remain part of New Mexico — in line with their identification of culture, heritage, and way of life — and lost, resulting in a divide still felt by some today.

In her book “Pleas and Petitions: Hispano Culture and Legislative Conflict in Territorial Colorado,” author Virginia Sánchez reexamines just how the state line between Colorado and New Mexico came to be. Her book is a culmination of two decades of research.

“I started asking questions about Southern Colorado,” Sánchez said. “And no one could tell me. I decided, Okay, this is my quest.”

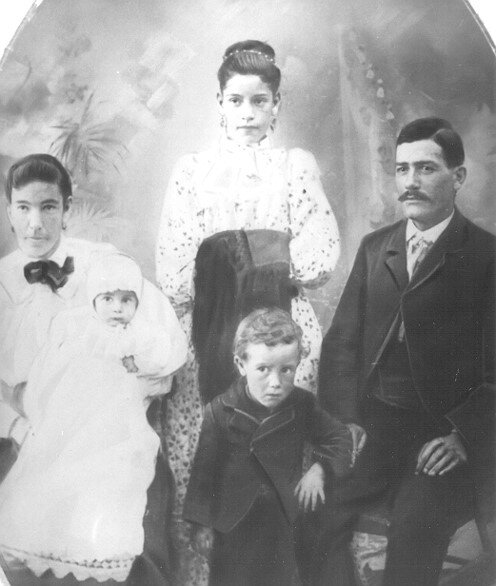

Intrigued by her own family history, Sánchez’s calling as a historian came early on.

“I tried to ask as many questions as I could,” Sánchez said. “Once, I was asking my grandmother about her marriage. She went to the drawer and pulled out this tablet paper. And it was all folded up. That was her pedimento — a request for her hand in marriage.”

Sánchez was blown away by the significance of the artifact.

“I’m just there, like, ‘Wow. Wow,’” she remembered.

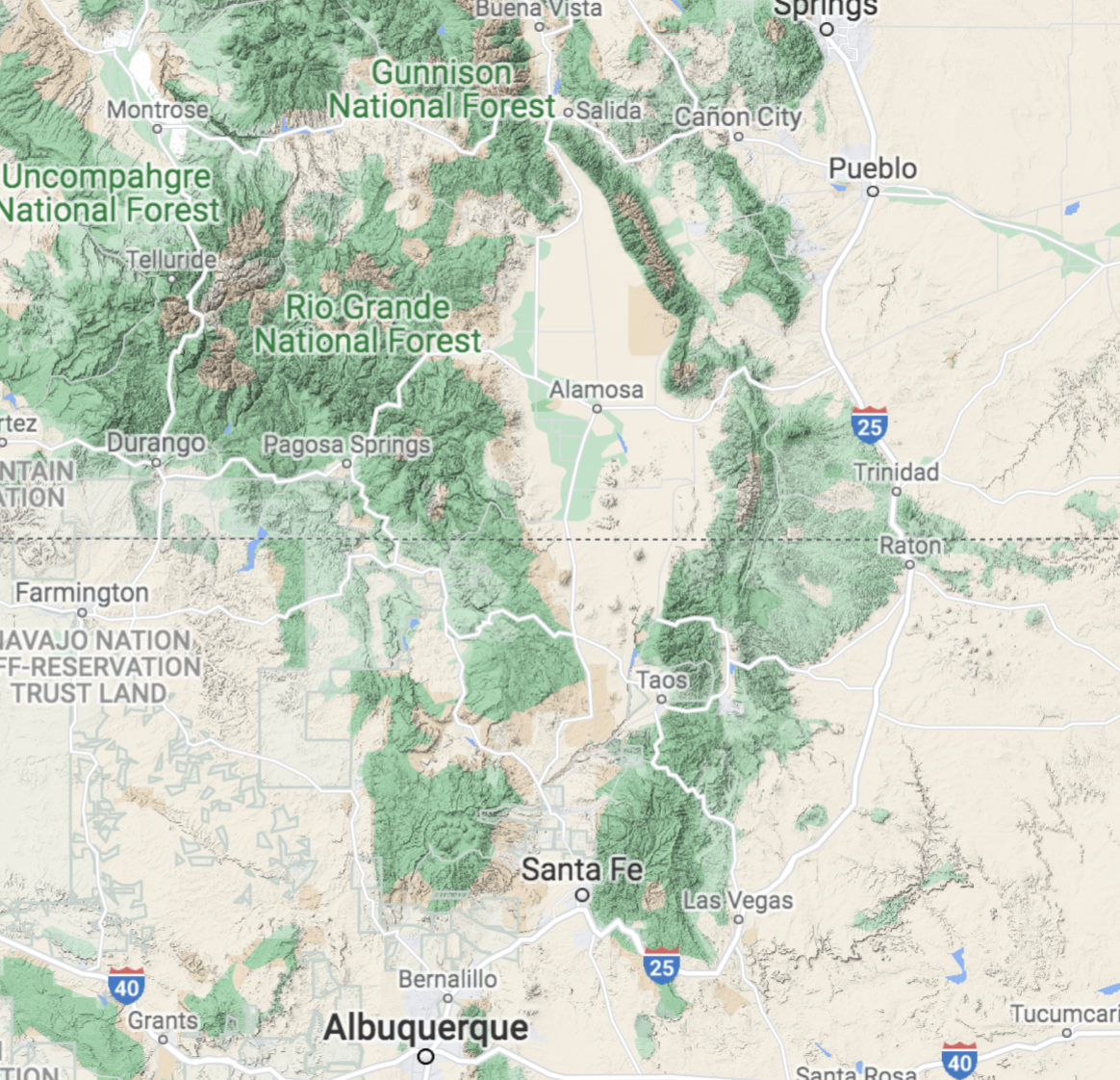

Originally from Mora, New Mexico, Sánchez’s grandparents farmed with hand-dug acequia irrigation infrastructure deep in the Sangre de Cristo mountains south of Taos.

Back then, this area was Mexican Territory. Sánchez’s great-grandfather was a justice of the peace, and his father was a lawyer — two occupations that were dissolved with the changes in citizenship and legal process that followed U.S. acquisition.

Sánchez was raised in Wyoming, where her family and many others, she said, migrated after World War II.

“The men could no longer find jobs in Mora,” said Sánchez, “so they moved to Wyoming with the railroad. We’d go back [to New Mexico] regularly.”

Sánchez decided to document regional culture when her mother-in-law presented her with a copy of an old acequia ledger from Huerfano County. The 1884-1912 ledger listed the names of water rights’ holders and marked their participation in the annual spring cleaning — all in Spanish.

“I gently touched those pages, and I just thought, Oh my gosh,” Sánchez recalls. “From that, I started researching those names.”

Among them, Sánchez uncovered residents forced into Indigenous enslavement. She researched their stories, eventually creating reports of genealogy which she passed on to descendants.

During this process, she learned that many Hispano families from Huerfano County came from the San Luis Valley, but pushed north during the influx of Westward Expansion — bringing their irrigation systems, customs, and language with them.

Beginning as early as the 1840s and 1850s, around 7,000 primarily Spanish and Mexican colonists settled across what is now the San Luis Valley.

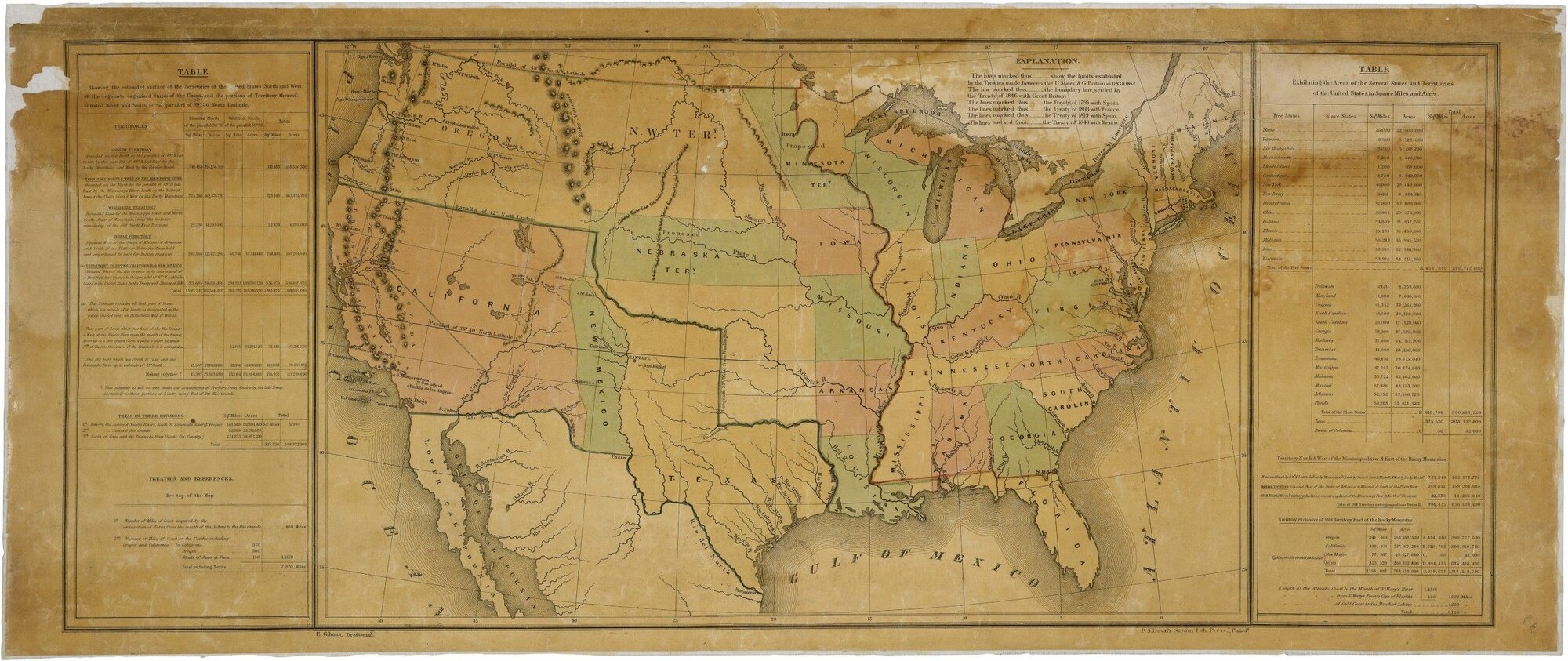

Not long after, the Westward Expansion converged from the east. In 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican American War and relinquished the area as a Territory of Mexico, creating in its stead the Territories of Kansas, New Mexico, Utah, and Nebraska. The San Luis Valley fell into New Mexican Territory.

Early settlers maintained small farm and ranch operations as land and mineral prospecting soon defined the region at large.

“When miners arrived in 1859, they kind of took over the place,” said Sánchez.

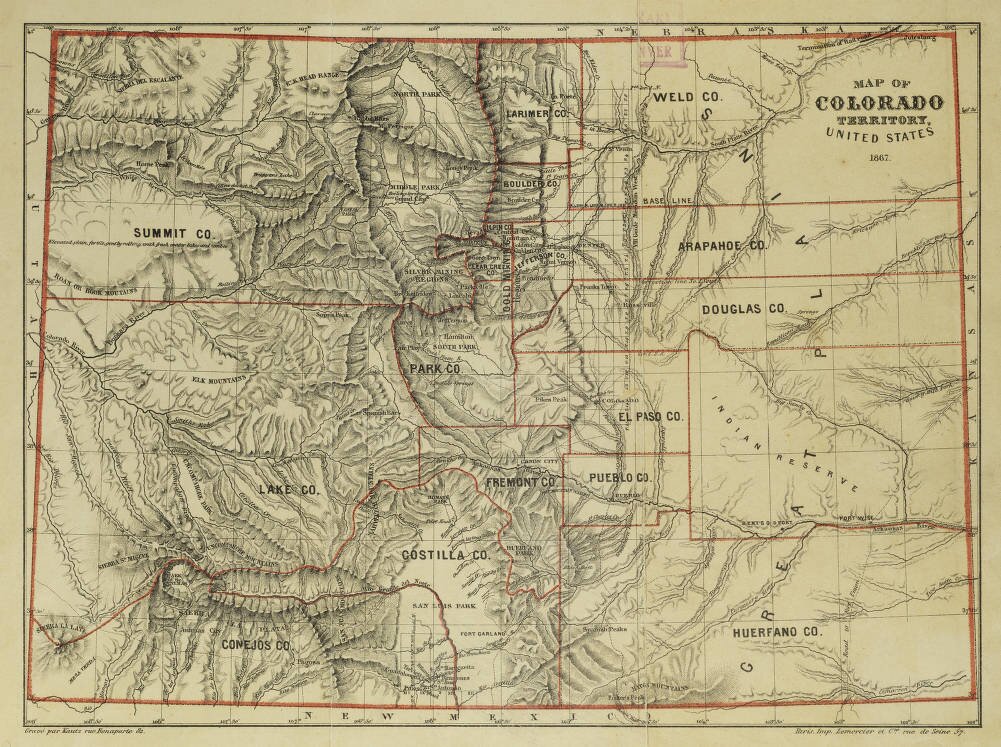

And the new residents wanted to create a new territory, so they drafted a square map — including the so-called “notch” of New Mexico Territory today known as the San Luis Valley.

Statehood was the ultimate goal, said Sánchez.

“In order to have statehood, you had to have 60,000 citizens in your territory,” she said. “Without the 7,000 Hispanos of ‘the notch,’ they would not have had that. They were intent on keeping this population within Colorado Territory for that sole interest.”

New Mexico Territorial delegate Miguel Antonio Otero, for whom Otero County is named, was sent to dissuade the north from enacting the change in border, citing “too many differences,” said Sánchez. “Tradition, language, religion... he told Congressional members that you shouldn't take people away from what they know as their family.”

“Otero plead with Congress: ‘If you do this, they're going to petition to be returned,’” Sánchez added.

Otero asked for a vote to be put to the people, but the request was refused.

As a result, 7,000 settlers in New Mexico Territory "woke up one morning in 1861 and they're suddenly in Colorado Territory,” said Sánchez. “They're now under an English-speaking governance, with English laws and new settlers are coming in.”

It was a cultural shock, according to Sánchez. Residents found themselves adjusting from a barter and trade economy to a cash economy.

“Now they had to pay taxes. How were they going to pay taxes when they didn't have hard cash? They had to sell their property, their livestock. Some had to indenture their son or daughter,” she said.

The system of land ownership also shifted overnight.

“Some land deeds were rejected because they did not conform to 1861 Colorado real estate law,” said Sánchez. “Others were never approved.”

The use of common lands and other provisions critical to survival as deeded by the Mexican Land Grant system were denied in most cases, Sánchez said. Access and stewardship of publicly held resources like grazing, fishing, hunting, and firewood and timber collection did not carry over (with one rare exception).

Industry and railroads also catered to Anglo settlers, Sánchez said. Some intentionally built facilities far away from earlier settlements. “That separated people, so this part of the town was the Mexican side; and this part is the Anglo side,” said Sánchez.

The new border despaired natural watershed systems and wreaked havoc on ranching. If an animal were to stray unknowingly over the territorial line, residents were subject to impounding of livestock and daily fines they often could not pay, Sánchez said.

Weather and road conditions frequently kept representatives from making the arduous trip north over La Veta pass to attend Territorial legislatures.

And, accustomed to a bilingual legislature, southern Colorado residents had another newfound barrier: language.

“In New Mexico Territory, there was a budget for translating laws from English into Spanish,” said Sánchez. “Colorado had none of that.”

Colorado Territorial Council representative Celestino Dominguez petitioned the Treasury, asking for federal monies to publish laws in Spanish. The response from the Treasury was that “these settlers were not U.S. citizens,” said Sánchez. “They were told instead they needed to learn English.”

This “began a loss of language used in the area for 400 years,” said Sánchez. “It’s painful. We have a right to our language and our traditions.”

“There's disparity,” Sánchez noted. “By the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, these residents are U.S. citizens, able to vote; and they did vote in the first territorial election in 1861,” she said. “But then they're called ‘Mexican’ and told to learn English.”

The Colorado Territory existed from 1861 until statehood in 1876. But by 1862— just one year after being absorbed into Colorado Territory — the people of the San Luis Valley “notch” had issued a campaign of pleas and petitions to be returned to New Mexico.

A New Mexico newspaper called for secession of “the notch,” writing that Congress “needed to restore the part that was unjustly dismembered from New Mexico Territory,” said Sánchez. “The newspaper said this should never have been done.”

“And they almost did it in 1864 — but the Congressional session ended,” said Sánchez. “By the next session, they were busy taking care of the end of the Civil War and reconstruction.”

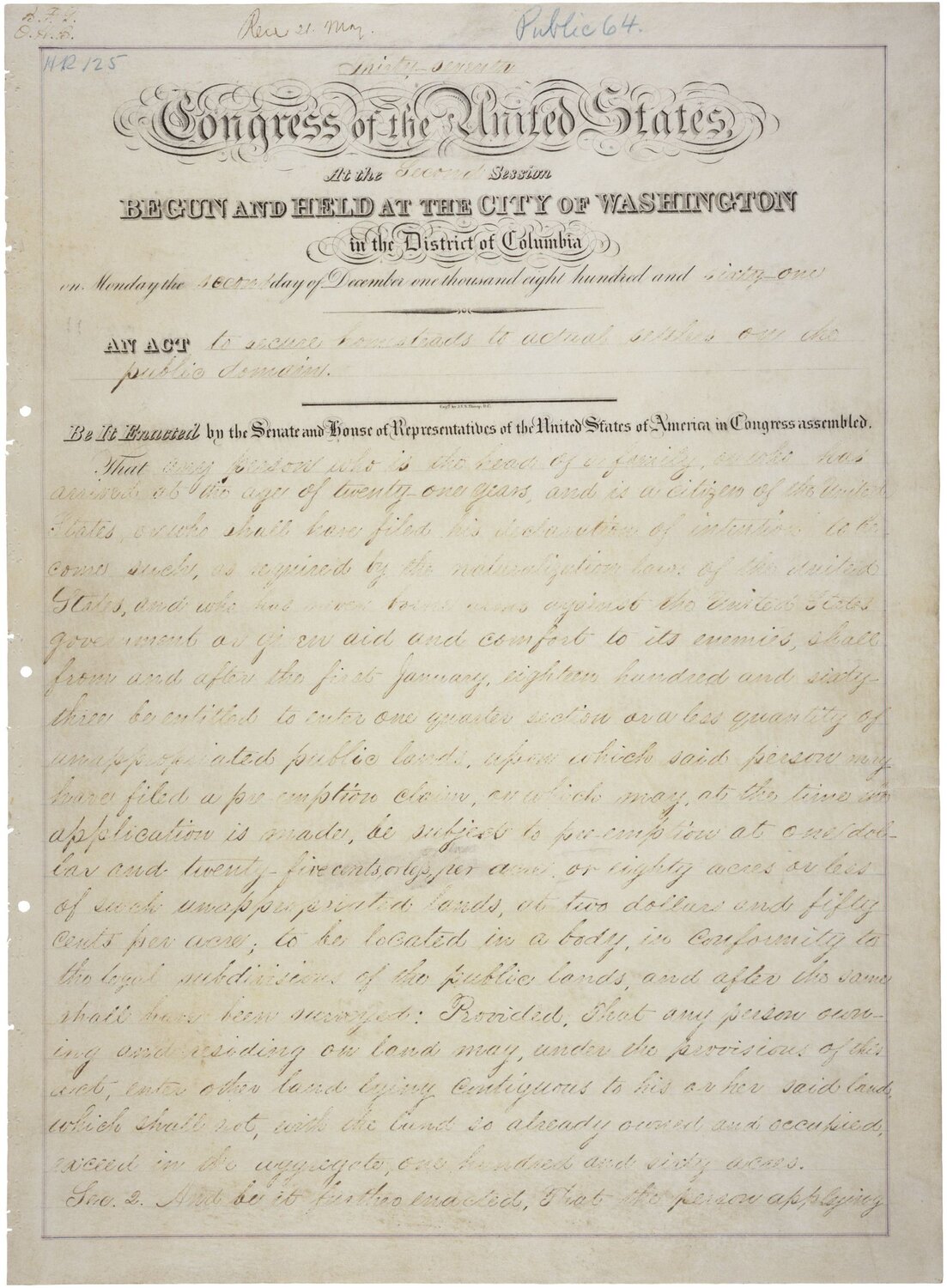

By then, the allure of gold and mineral resources had fully captured the Territorial economy. The endless Valley floor was ripe for the Homestead Act of 1862, and Hispano and Mexicano settlers were next to be displaced.

Sánchez said advertisements from the East purported “cheap Mexican land for sale,” and some land grabs occurred within pre-established agricultural communities.

But this was far from all that was happening in the region.

“Colorado was first Ute country, and we have to remember that. And we should pay tribute to that,” Sánchez said, recognizing that many generations of families and cultures were already displaced before any settlement occurred.

Native Americans were subject to removal, violent interactions, and enforcement of the overriding laws and regulations. New diseases emerged carried by miners and settlers. Buffalo and wildlife stock diminished due to population growth, Sánchez said, creating famine. A rapid deterioration of subsistence also occurred. Indigenous peoples’ access to a regional traditional lifestyle was phased out in part by reliance on rations supplied by Territorial Indian Agencies. Access to these rations was often indiscriminate and inconsistent, Sánchez’s research revealed.

“And the types of rations that they're receiving, you know, they're moldy when they get here from Denver,” she said. “Then, if they didn't get their rations, they still needed food. Where were they going to go? They'd go to the settlers. They would make raids on the sheep or raids on the crops,” Sánchez said. “There’s a lot of loss there, for everyone.”

“A military district moves in that’s trying to protect the settlers and minors,” said Sánchez. “Then you have the United States Army battling in the Civil War. Then there are the Indian Wars going around. Everybody was hurting.”

Sánchez added that the Hispano settlers felt that the military was there to watch them, to make sure that there wasn't another uprising like the Taos Revolt.

In 1862, instances of "secret meetings” held by Hispanos to protest taxes were reported to officials by an Anglo merchant, said Sánchez.

Newspapers reported that “the ‘Mexicans' were ‘planning an insurrection,’’ Sánchez said. During her research, Sánchez unearthed records of the merchant meeting with a local Indian agent to receive advice about what to do in the case of an insurrection.

“This idea of an insurrection blows up more and more and more,” Sánchez said. “At this time, a Hispano Territorial representative by the name of Francisco Gallegos is found dead on the Conejos Plaza with a rope around his neck. The newspaper doesn't say anything more.”

In fact, any time a non-Anglo was killed or hung, they were identified only by perceived ethnicity — “not their name,” Sánchez said. “It was a real sad state of affairs.”

The battle for belonging never really came to an end, Sánchez notes, with legislative debate on the issue taking place throughout the 1860s.

In 1870, legislation was introduced in the New Mexico Territory to annex Colorado’s Conejos and Costilla Counties back to New Mexico, but the issue fizzled.

To this day, the loss is felt, said Gaby Aragon, a former Town of San Luis Council Member whose family roots go back eight generations in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico.

“When this section of the state in the San Luis Valley was severed from New Mexico, there was an entire history, culture and way of life that was lost, spinning us into an identity crisis,” Aragon said.

It’s a sentiment she said is frequently expressed in her community.

“The consequences from that move had lasting and detrimental impacts,” she said, from acequia water law and land grant administration to cultural recognition and validation.

Aragon's extended family still uses the barter system to trade things like sheep, seeds, and fruit with northern New Mexico residents. There remains a disconnect to the rest of Colorado because of the geographic and cultural isolation, Aragon said, noting it can feel like the only time people seem to pay attention “is when someone is after our land and our water.”

“The voices of southern Colorado do struggle to maintain their voice legislatively,” she said. “In many ways, we are the forgotten voices.”

“Without a doubt, there’s a rural-urban divide,” said State Sen. Cleave Simpson (R-Alamosa). “The San Luis Valley has always felt a little bit left out. Though in a lot of cases, it’s a ‘leave us alone’ approach, as well,” he observed.

Simpson said he wasn’t familiar with historic attempts to return the southern part of the state back to New Mexico.

“As an Anglo-American, it’s probably hard for me to see that divide if it still exists, but I don’t doubt that it probably does,” Simpson said.

A fourth-generation farmer and rancher from Alamosa, Simpson shared that his wife’s family, like so many others, once migrated north from New Mexico to the San Luis Valley.

Across the border, former Republican U.S. Rep. Bill Redmond said that when he was elected in 1997, there was a lot to be learned about the relationships between northern New Mexico and southern Colorado.

Because he was from Illinois, “There was a learning curve. We didn’t have land grants on the South Side of Chicago,” he explained.

Redmond discovered everything from the economy to watersheds to genealogy spilled across state lines — and his research made a direct correlation between lost land grants and material poverty.

“Those are some of the realities that are still at play on both sides of that line,” he said.

Education may be the strongest ally.

Last summer, Sen. Simpson teamed up with Colorado Competitive Council, an offshoot of the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce that arranges for legislators to tour each other’s districts.

“I got to put 10 legislators and about 30 lobbyists on a bus and drive them from Denver to Alamosa,” said Simpson. “Some of them had never been here. They were amazed it’s this far. Then, I took them to San Luis. Everyone was just awed at the natural beauty and at the connection people have with the land in the area,” he said.

Growing up in Alamosa, Simpson said he would cringe watching Denver news when the weather would refer to Colorado Springs as Southern Colorado.

“Once you get south of Pueblo, you get a lot of history that a lot of people in Colorado just don’t know about,” said Marisa Zamudio, a 2021 California Polytechnic state University graduate with family roots in the San Luis Valley and northern New Mexico.

Sánchez agreed that regional curriculum tends to skip this history.

“You often don’t learn this information until you get to college-level studies,” she said. “And that’s unfortunate. We always ask, ‘How do we engage more minority students in education?’ You do it by teaching them what they are familiar with. Children need to be motivated by their own stories.”

“It’s important that people know their own histories, and know them accurately,” agreed Zamudio, whose work researching the contemporary regional effects of settler-colonialism served as the foundation of her thesis. “A lot of people don’t have access to this information.”

Borderlands of Southern Colorado, an initiative of History Colorado, aims to bridge this exact gap. Pre- and post-Treaty narratives are highlighted statewide through exhibits, programs, and experiences.

“This isn't just a southern Colorado story; It's a Colorado story,” said Eric Carpio, Director of the Fort Garland Museum and Cultural Center. “This history impacts everything, even 160-plus years later."

"The defining moments in southern Colorado history, from the Maestas desegregation case, to the ongoing struggle for access to La Sierra, carry many of the same themes — themes of resistance, preservation, and resilience,” he said.

“I don't think it's a stretch to say that even contemporary issues like the threat of water being pumped out of the Valley, or decisions about Congressional redistricting, are steeped in events of the past.”

"People in southern Colorado have had to fight, figuratively and sometimes literally, in order to be acknowledged,” he said, “as well as to preserve their land, water, language, and way of life.”

Robert Ruybalid, known as “El Mogoté,” of the small village of Mogoté in Conejos County, created the Forgotten Southern Colorado Facebook group as a means of sharing this forgotten history.

“I never intended to perpetuate the memories,” Ruybalid said, “but now it’s my mission.”

He was inspired after joining the “Forgotten New Mexico” Facebook group, which he said wasn’t necessarily inclusive of material from across the state line — despite the cultural relevance.

“They told me to start my own group,” he said. “So, I winged it.”

A robust online community soon formed into a full-fledged anthropological self-study, with nearly 23,000 local, regional, and once-so national contributors posting family photos, genealogy, memories, recipes, and definitions of words from the hyper-local dialect — borne of Spanish, Arabic, and Nahuatl.

Group members routinely learn they are related through photo threads, and members enjoy heartfelt recollections of everything from local traditions to bygone businesses — keeping southern Colorado at the forefront of collective memory.

In the description for the group, Ruybalid makes sure to acknowledge — New Mexico photos are allowed.

Kate Perdoni is a multimedia journalist for Rocky Mountain PBS. Reach them at kateperdoni@rmpbs.org or on Instagram @kateyslvls.