Colorado has a complex land and ethnic history. One student is looking at the correlations.

DENVER — Do you have indigenous roots? What languages were spoken at home growing up? Where did your food come from?

These are just a few of the questions Marissa Zamudio is asking regional communities in a survey supporting her thesis work at California Polytechnic State University.

The survey, available in both Spanish and English, explores individual and community identity and heritage in North Denver, southern Colorado’s San Luis Valley, and New Mexico. It’s part of a larger study by Zamudio on the impacts of settler-colonialism — both historic and contemporary.

“A lot of people think colonialism is a thing of a past,” Zamudio said. “They will say, ‘That happened a long time ago.’ But the truth is, we are still experiencing the impacts. It’s ongoing.”

Zamudio said the pandemic and recent social justice campaigns have helped expose that these inequalities continue.

“But only to the people who had the privilege of not knowing about it before,” she said. “All of our communities already knew the issues. We’ve been taught an incomplete definition of racism.”

To explore how identity is shaped by lived experience, Zamudio, who studies Political Science, Global Politics, and Ethnic Studies, brought her research home.

“To understand where you come from, you have to study your communities,” Zamudio said.

Zamudio was born and raised in Denver, where her father’s family has roots. Her mother’s family came from northern New Mexico to the San Luis Valley of southern Colorado into the small settlement of Los Sauces.

“I spent a lot of my childhood in North Denver, and also in southern Colorado,” said Zamudio. “These places have influenced me — and I want to see how others have been shaped by these communities and experiences over time.”

Growing up, Zamudio noticed common issues faced by her communities. There was a neglect in health care access. There were no grocery stores. They lacked quality public schools.

“I quickly discovered a common thread that goes back to settler-colonialism,” Zamudio said. "I was wondering if other people in my communities were feeling affected in these same ways. I knew I couldn’t be the only one thinking about these things.”

In North America, settler-colonialism is defined as the process by which indigenous peoples of the land were killed, forcibly displaced, culturally assimilated or erased. More than 9.5 million Natives were killed in what is now the United States, with just 300,000 remaining by 1900, according to estimates.

Zamudio uses both auto-ethnographic and ethnographic approaches. Her own heritage reflects a confluence of cultural identities.

“We have a lot of Native blood in my family, especially on my grandfather’s side,” she said.

In the San Luis Valley, the convergence of indigenous, Native, Mexican, Spanish, and other European settlers creates unique implications for self-identity. Zamudio herself struggled with self-definition.

“One of the biggest themes of my project is how settler-colonialism has affected the ways people conceptualize their identity,” Zamudio said. “Who we are — how we self-identify — depends on a lot of things.”

She began to explore aspects of how identity is shaped, like regional history curriculum in schools, individual processes of assimilation, and the maintenance and loss of traditional ways. Zamudio’s research has helped her understand why some chose not to claim indigenous heritage throughout history.

For many, she says, “Native people were trying to avoid the shame they were faced with for existing.”

“Many claimed another heritage for protective reasons,” Zamudio continued. “Natives were being sent to boarding schools to learn how to be white. They didn’t want to have their kids sent away. And, many indigenous people said they were from another race so they could pretend to be settlers and stay on the land they were from. They didn’t want to be sent to reservations. They wanted to live on land they had a connection with.”

Another theme Zamudio sees is lateral violence.

“This is when people of color tell other people of color that they are not ‘enough’ of a certain thing in order to be included,” she said. “A lot of non-enrolled Natives have been told that they ‘aren’t Native’ because they are not enrolled, for example.”

Zamudio herself is an advocate for sovereignty of self-identification.

“It’s not anyone’s place or business to decide for someone else what they are,” she said.

Zamudio said these issues still affect representation today.

“People were colonized to believe they should not claim their indigenous heritage,” she said. “To this day, many people with Native ancestry don’t report it.”

From census records, Zamudio has seen how government classification also affects representation.

“In the census, one year a person is listed as ‘Native.’ Years later, they are then listed as ‘Hispano,’ and eventually, that morphs into ‘White,’” Zamudio said. “As the years go on, for some, Native identity can be essentially erased.”

Native people have historically been one of the most undercounted groups in the United States census. For the first 70 years of the census, they were not counted.

“And much of tribal enrollment is based on blood quantum, which is self-defeating,” Zamudio said. “It’s a form of statistical genocide. The idea of ‘pure blood,’ or blood quantum itself, is a colonial logic. As time goes on, a lot of people aren’t going to meet the ‘requirement’ for blood quantum. It’s a real challenge that people face.”

Zamudio also studies the culture of genízaros, Natives from present-day southern Colorado and northern New Mexico who were taken captive by Spanish settlers or given to settlements by other Natives through war or ransom payment. Genízaros were used for labor as indentured servants, and detribalized over time, losing access to cultural and ancestral knowledge.

Significant portions of the populations of present-day northern New Mexico and southern Colorado, areas of Zamudio’s study, are descendants of genízaros.

“Even though they were Native, genízaros became ‘Hispanicized,’ and lost ties and direct tribal connections,” Zamudio said. “Many of their descendants don’t have the direct tribal enrollment opportunities that others do.”

Zamudio’s survey asks participants what race and ethnicity they identify as, qualifiers she says people commonly mix up or mis-report.

“I grew up saying, ‘I’m Mexican,’” said Zamudio. “But Mexican is a nationality. I’m understanding now that most people do not understand the difference between race and ethnicity. Almost everyone in the survey either gets the two confused, or put something that isn’t a race or an ethnicity in the box. And even though race is a social construct, it has very real material effects.”

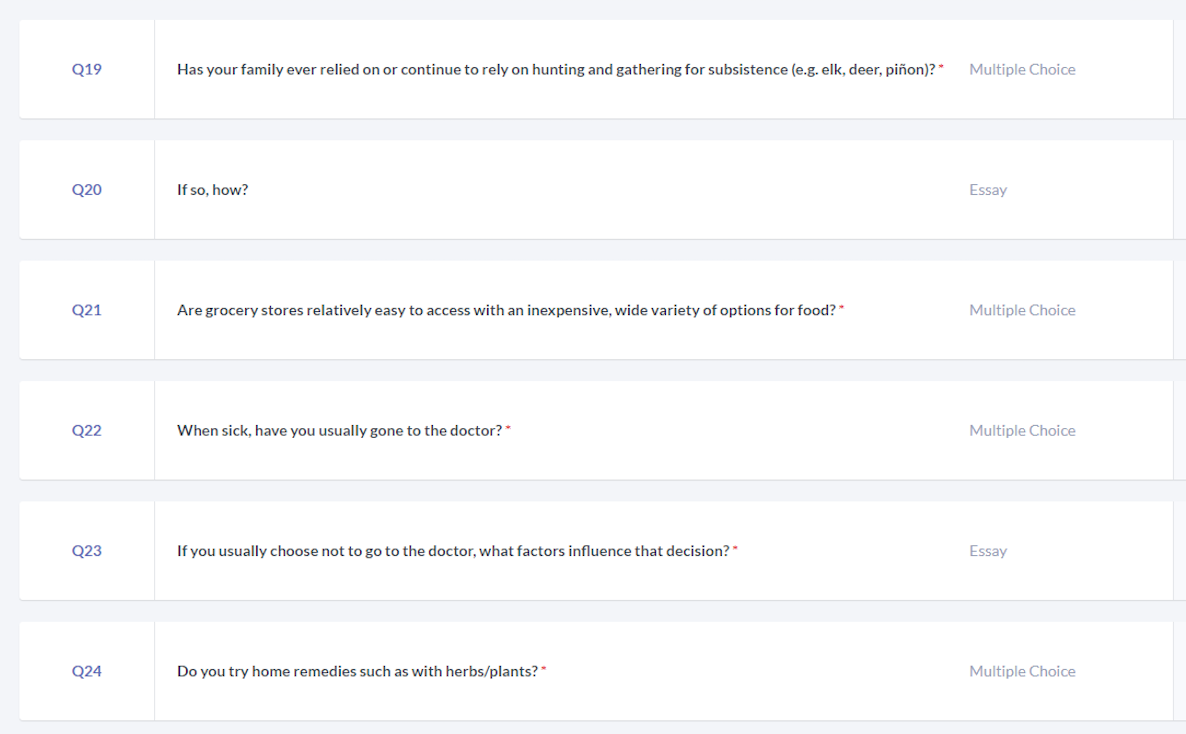

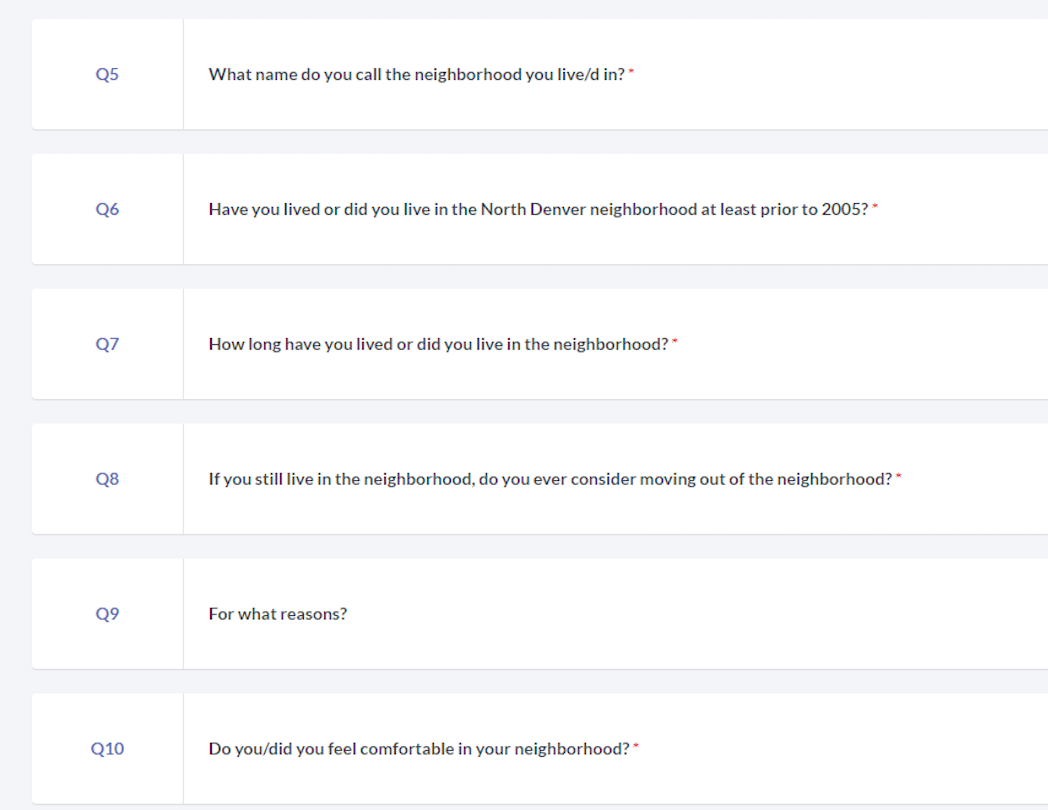

The survey also queries longtime residents of North Denver, defined as having lived in the area for at least 15 years.

Questions include, Do you feel comfortable in your neighborhood? Have real estate agents made offers to you on your home?

“Part of the survey is looking at issues of gentrification and development in North Denver. I am curious about people’s attitudes,” she explained. “Do people see this as a good thing? Or is it a negative thing, because there has been culture lost?”

The survey captures ways Chicano and Mexican American people have been displaced, primarily by younger, higher-income white people.

“Mexican American people have lived in these Denver neighborhoods for a long time,” Zamudio said. “But then — it’s not their land, either. It belonged to many indigenous nations. Prior to settlement, there was no concept of land ownership. All around us, there is claim to land that isn’t necessarily ours.”

“It’s all very complex,” Zamudio added.

Zamudio said her grandmother grew vegetables to feed the family in an urban garden behind her house in North Denver. Recently, the plot, which since became Denver Urban Gardens, was sold for development. The land, purchased for $1 in 1988, sold for $1.2 million in September 2020.

“Growing up, my grandparents used that land for food,” she said. “My grandma would be in the garden and use the vegetables for dinner. There weren’t grocery stores in the neighborhood. And now, there are — and they are really expensive stores.”

“It’s kind of just all about money,” Zamudio added. “Folks are willing to ignore the fact that these policies disproportionately affect people of color.”

While some struggle to maintain their culture and neighborhoods, others align with assimilation, Zamudio said.

“No one wants to face discrimination,” she said. “One of the biggest challenges of organizing in communities is that you have those who want to assimilate for the sake of not being discriminated against, and then you have others who fiercely want to keep their identity, and insist they belong here.”

Self-identity is a large component of community and individual health, and of a thriving life, Zamudio said.

“Trauma can be passed down through generations, coded through our genes,” she said. “Seeing the ways in which our ancestors dealt with so much, and how that trauma was passed down, helps explain the ways in which trauma manifests and reproduces in a cycle from generation to generation. Often it manifests as anxiety.”

Zamudio hopes to publicly release her findings within the communities they focus on, to help support education and validate individual identity.

“So many people have gone through similar experiences to what I have,” she said. “This auto-ethnography and ethnography is a way for me to heal, and hopefully have my communities heal as well.”

Her research, she says, is also an acknowledgement of her gratitude and privilege of being able to attend college.

“In what ways can I support and give back by having the privilege of having this education?” she said. “I want to make things better, and help people understand their history, and hopefully want to stay there to continue on.”

Surveys:

For those who are from Southern Colorado or New Mexico:

- Spanish version: https://s.surveyplanet.com/zhHJZm3nV

- English version: https://s.surveyplanet.com/BBMIvGfk0

For those who are from North Denver:

- Spanish version: https://s.surveyplanet.com/qPtGRTRcb

- English version: https://s.surveyplanet.com/1wrVfPZR4