New exhibit in Fort Garland explores the lesser-known history of enslaved Native Americans

At a San Luis Valley museum once dedicated to commemorating the infamous U.S. Army commandant Kit Carson, community members, historians, and an artist are uncovering another story: a long, oft-forgotten history of enslaved Indigenous and Native American inhabitants, both pre- and post-Emancipation Proclamation. This work and exhibit are part of Fort Garland Museum's ongoing movement to acknowledge those peoples and their descendants affected negatively by the impacts of settler-colonialism.

FORT GARLAND, Colo. — At the base of the sacred mountain Sisnaajiní (Mount Blanca), the traditional eastern boundary of Dinétah, the Navajo homeland, a different totem—one of western conquest and expansion—is being reimagined, and another history told.

Visitors to the Fort Garland Museum & Cultural Center have long been invited to explore fort grounds and view exhibits inside a collection of restored adobe buildings. Lately, things haven’t looked quite the same — the museum is amending a historic narrative it has held exclusively for nearly seven decades.

“We originally had a Kit Carson exhibit throughout this space, with representation of what life would have been like in a nineteenth century military fort,” said Dianne Archuleta, Director of the El Pueblo Museum 100 miles northeast of Fort Garland. Like the Fort, El Pueblo is operated under History Colorado.

“We’ve changed direction,” explained Archuleta. “We are now shifting the focus to the people who actually lived here, and whose lives were affected.”

Fort Garland was established in 1858 to defend settlements in what became United States territory after the Mexican-American War. The Fort Garland area was homeland to many Indigenous and Native American communities, including Ute, Diné, and Jicarilla Apache. They faced war, raids, displacement, new economies and cultures, and were created into a welfare state without control over resources or supplies. The Fort was abandoned in the 1880s, once most Native peoples had been forced onto reservations.

“There were no happy outcomes for the people who were displaced — and the people who lost their culture, traditions, and livelihoods,” Archuleta said.

This legacy of conquest was once a central theme at the Museum, with Kit Carson in the spotlight. Carson served as commandant of Fort Garland for 18 months between 1866 and 1867. He was popularized in Western nomenclature as a scout, government courier, Indian agent, and soldier who ventured throughout the Southwest and West.

Now descendents, community members and historians are telling a different side of Carson's history.

Carson played a large role in the regional Indigenous slave trade industry, adopting an Indigenous son of his own whose relatives still live here today with the Carson name.

In Southern Colorado, both pre- and post-Emancipation Proclamation, “Indigenous people were part of the enslaved people's trade throughout time,” said Archuleta. “They were considered commodities, and were bought and sold. Raids were made upon Indigenous people, and they were taken from their tribes.”

Archuleta said captives were assimilated into the new households—whether Anglo, Spanish, Mexican, or another Indigenous culture—losing their names and Tribal relationships in the process.

“They were robbed of any of their Indigenous culture,” said Archuleta.

In a region characterized by a complex historic narrative and its resulting identities, Archuletta said these stories are common, though not always expressed, often because of stigma and trauma.

Archuleta has a personal connection to this history.

“I have an ancestor who was an Indigenous captive,” she said. “My great-great grandmother’s whole family was killed, except for her and her young daughter.”

Though her great-great grandmother tried to escape several times, “she really didn’t have anything to go back to,” said Archuleta. “They kept bringing her back. At some point, she had to accept her fate.”

“I feel like there are a lot of stories similar to that,” she continued. “We started this work to find those stories. They weren’t in any of the history books.”

Eric Carpio, Director of the Fort Garland Museum and Cultural Center, said the community has been central to leading the exploration and discussion of Indigenous enslavement.

“The way we’ve uncovered a lot of this history is through listening to people who have been impacted,” Carpio said.

Museum staff held virtual conversations to create an informative, healing space for people to process and collect information. ”In some families, this maybe wasn’t talked about,” said Carpio.

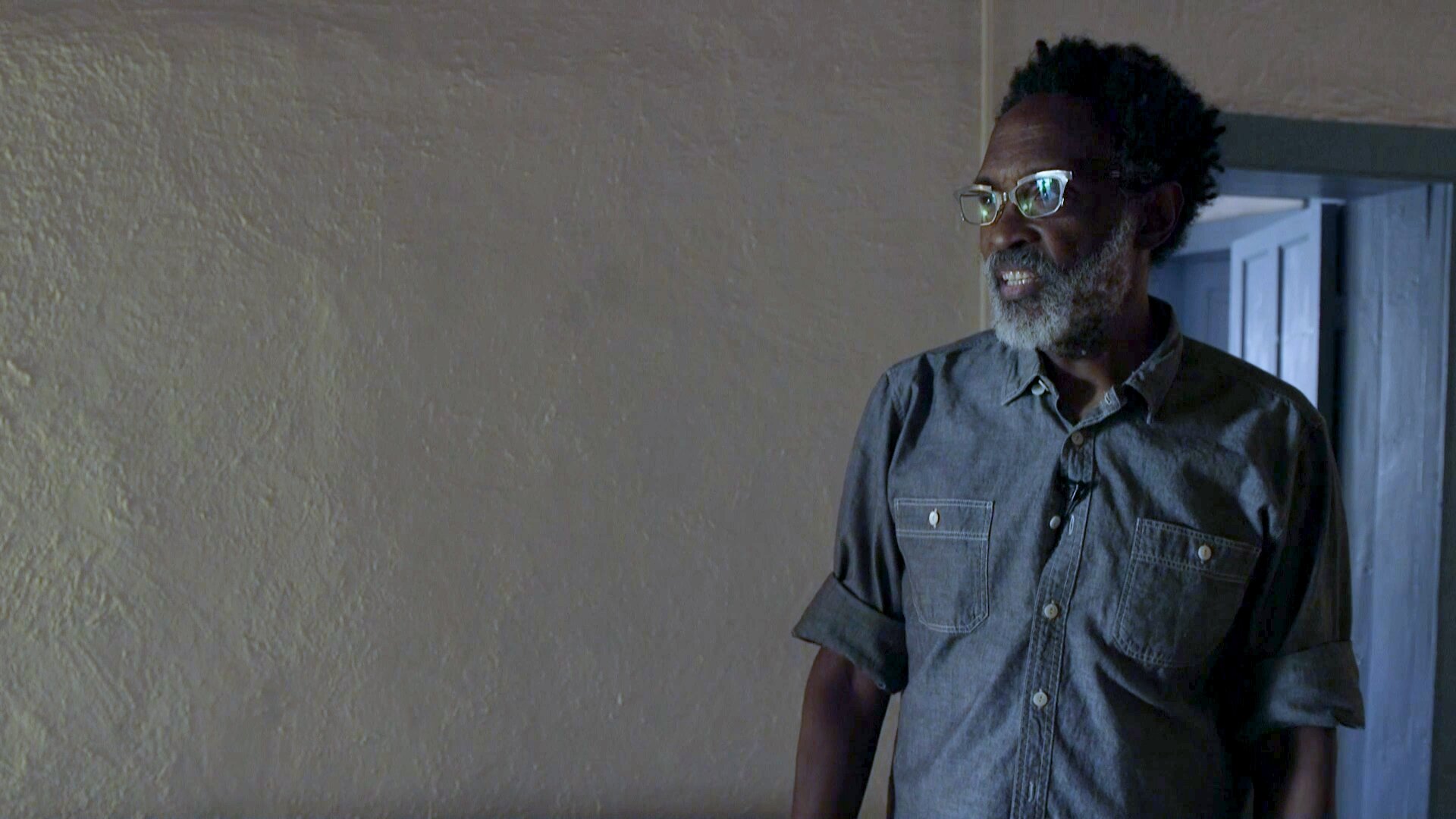

They also worked with former New Mexico State Historian Estevan Rael-Galvez and artist Chip Thomas, street name jetsonorama, on an inaugural exhibit to humanize and explore the history of Indigenous captivity that took place in the San Luis Valley and Southern Colorado.

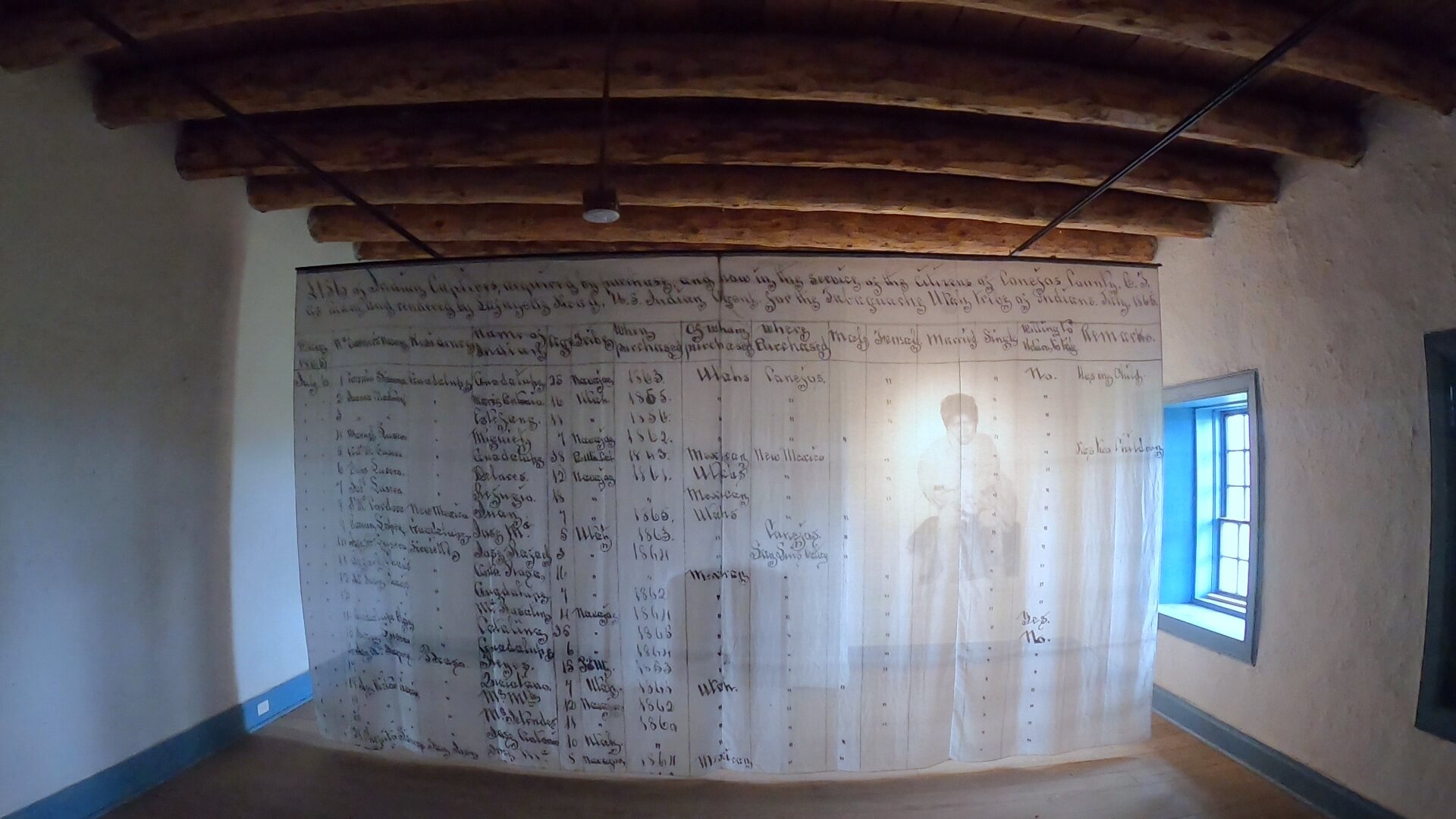

Thomas printed life-sized historic photos of Indigenous captives of the region researched by Rael-Galvez and others, and wall-sized cloth renditions of the lists of enslaved people of Conejos and Costilla Counties once commissioned by the United States.

Within the Commandant’s Quarters where Kit Carson once resided, Carson’s own Indigenous captive, Juan Carson, an enslaved Navajo person, now looks back.

“He belongs in this house in a big, powerful way, having lived here,” Thomas said of Juan Carson. “It became poignant, because he is representing his home.”

In creating the exhibit, Thomas said, “I was aware of the weightiness of what I am attempting to express, and what I’m dealing with historically. This is such a complicated, nuanced story.”

Living on the Navajo Nation for 34 years, “I’ve heard stories about distant relatives of people having been captured and taken away from their families,” he explained.

Thomas went to the reservation as a physician and visual storyteller in 1987, working a four-year requirement in a health shortage area to repay medical school. When that time was up, “I chose to stay,” he said.

Shortly after arriving, Thomas began documenting life on the reservation with film photography. A love of street art — and influences including French photographer and public artist JR’s work in the favelas of Brazil — led him to create giant photographs to scale, and putting them in public spaces on the Navajo reservation.

“It’s using a photographic medium, presented in a street art way, to tell an interesting narrative,” Thomas said. “This exhibition of Native enslavement is an opportunity to have a conversation about a difficult topic that the powers that be don’t want to be had.”

Tragic stories were uncovered through the unearthing of photo images used in the exhibit. Gabriel Woodson, an enslaved Navajo person, was 12 years old in a photo he stands for in his best clothes, positioned beside a doorway of the exhibit. Woodson became an alcoholic and was murdered in a bar fight in his late teens.

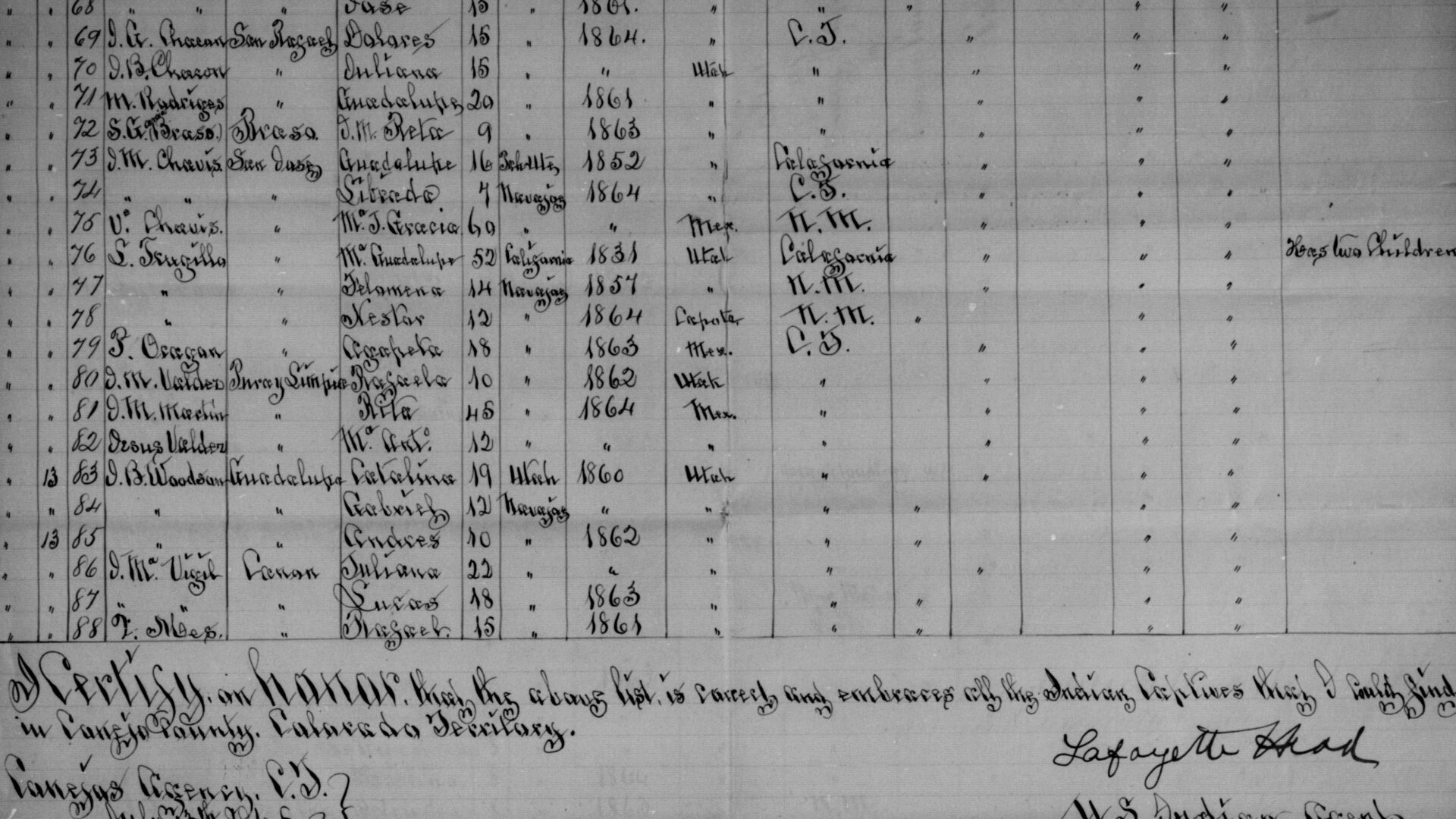

After the Civil War, President Andrew Johnson called on Indian Agents to survey communities in an attempt to determine the extent of Indigenous enslavement. Lafayette Head, Indian Agent of Conejos County, took tallies of certain captives in Conejos and Costilla counties.

These lists, commissioned just months after the end of the Civil War and the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln in 1865, detail more than 160 enslaved people.

Agents were found to have not disclosed their own captives, nor does the list include what Head called a “large number of captives that have legally married in the two counties.”

“Not only does Head not list his own captives on this list, but in the letter he writes to Governor Evans, he calls the practice ‘barbarous and inhumane,’” Carpio said. “He’s outraged in the letter to the Governor — but then isn’t completely transparent himself.”

“At one time, the military had thought that Head made most of his money based on the sale of Indigenous slaves,” said historian and author Virginia Sanchez. “By 1870, he was the richest man in Conejos County.”

Sanchez’ research into the National Archives for her book, “Pleas and Petitions: Hispano Culture and Legislative Conflict in Territorial Colorado,” unearthed a number of charges against Head by the local community — and the government — during this time.

In addition to determining that Head’s Indian Agency interpreter was not proficient in the Ute language, and that Head himself had withheld government provisions from Natives, speculated in government property and participated in “grub-staking”—or anonymously funding and profiting from territorial ventures—a note in the National Archives also states that Head was accused by the military of selling Navajo children.

“Due to captives’ research, and genetics today, we also know that Head had several illegitimate children by Indigenous persons and Hispanos,” said Sanchez. The longest-running Indian agent in Colorado, Head held the position for eight years, said Sanchez.

“People need to know this history,” said Sanchez.

Archuleta said the exhibit has created an opportunity for healing, both personally and as a community.

“chip’s exhibit has been instrumental, and this work has been instrumental in helping people understand what their history was — and that they are a part of this history,” Archuleta said.

“Personally, I feel like I have found a place of where I come from,” said Archuleta. “Finding out about this ancestry is like finding out that there was a piece that was lost that you could have had. At the same time, you have to recognize that you may not be here if that hadn’t been what our ancestors went through.”

The crisis and awareness of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Womxn are still direct throughways from this history, said Archuleta.

“Stories of people of color have always been left out of the narrative,” said Archuleta. “The national discourse has made this even more relevant.”

The Museum is committed to connecting descendants and community members with scholars, research, and archives to learn more.

“No bit of information is too small, or insignificant, in this story,” said Carpio. “We’ve had several examples of people who have come forward because of a rumor they had heard from an aunt or a grandmother.”

Archuleta hopes this reframing will support a history that is “equitable across all historical narratives. Everyone wants to talk about the ‘happy outcome.’ But that wasn’t the case for everybody that was in this region.”

Fort Garland Museum & Cultural Center

Unsilenced: Indigenous Enslavement in Southern Colorado is part of the Landlines Initiative organized by M12 STUDIO.

- Hours: Monday-Saturday, 9 am-5 pm

- Contact: 719-379-3512

- Parking: On-Site, Free

- For questions about the exhibit or ancestral work, email eric.carpio@state.co.us.

To learn more about Conejos and Costilla Counties, part of southern Colorado’s south San Luis Valley, watch Colorado Voices: Conejos and Costilla Counties Thursday, August 12 at 7 p.m. on Rocky Mountain PBS.

Kate Perdoni is a multimedia journalist for Rocky Mountain PBS and can be reached at kateperdoni@rmpbs.org and on Instagram at @kateyslvls.