Cheap Land | More subdivisions, more problems

COSTILLA COUNTY, Colo. — There are three residents per square mile in Costilla County, and almost a mile of official road for every two people. Hundreds more miles of unofficial roads criss-cross the prairie. The reason is simple: subdivisions.

Whether any given mile of road is drivable or not depends on what you’re driving. Routes here are sliced across isolated prairie lots often overgrown with grasses and wildflowers, and sometimes barely visible.

An unmaintained prairie subdivision road.

For over half a century, the marketing of off-grid, sage and juniper desert plots has created the subdivided estates of Costilla County as a brand-new experience. Magazine and television ads show living in symbiosis with the earth as easy, with blue skies and mountains in the backdrop of every scene. Barren five-acre tracts are a “great opportunity to own,” to “build your off-grid homestead ranch” with "a wonderful view of Ute Mountain in your back yard,” according to online land sales sites. In this “peaceful and quiet area, you are sure to not be bothered by anyone, as it is very secluded,” advertised one seller.

In reality, certain roads are sometimes impassable. There are no water hookups, gas lines, road signs, or amenities in this endless, beautiful, rolling, dry landscape. At first, few can even locate their land if not for the grace of neighbors. And there isn’t always a lot of grace. Having seen decades of new landowners drive in and then right back out again — some before they ever do find their plot — many locals now shake their heads.

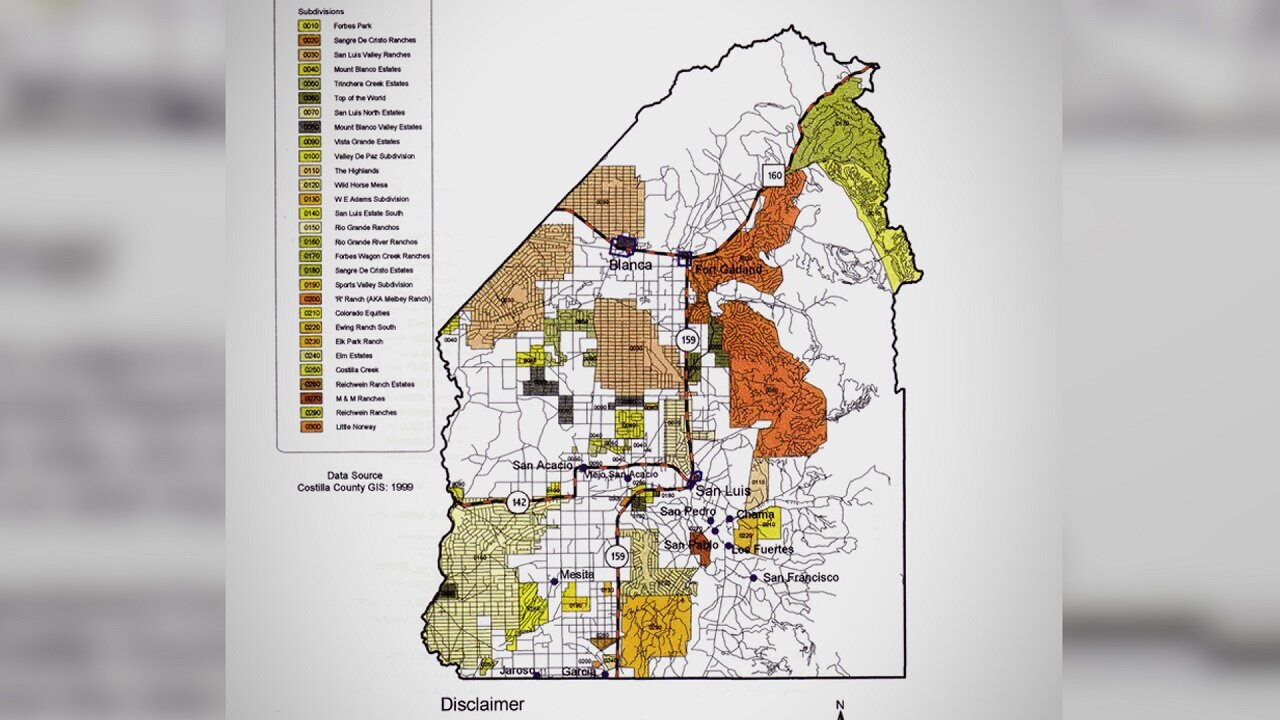

A 2011 map prepared by Costilla County. Shaded areas indicate subdivided estates. The county is 97% private lands.

Two decades ago, the prairie was uninterrupted, but for the tic-tac-toe board of bare-minimum dirt roads back and forth to the Rio Grande.

“Fifteen or twenty years ago, you'd go up in a mountain, look down, and it looked like everything was open space,” said Ben Doon, Costilla County Administrator. “It was hard to tell it was so subdivided.”

Today, thousands upon thousands of subdivided lots sit, still mostly vacant. But more folks than ever are trying to make a go, and life looks a lot different than the marketing brochures and television ads. Remnants of dreams and collections of left-behind building materials litter the landscape, along with half-started, attempted, gutted, abandoned, and burned-out structures.

“Back then, it was a lot less developed, and there was a lot less interest in living here,” Doon said. “We realize now that people have started to build out there, that there was so much private land cut up. And now, the pressures are greater.”

County stressors include jail capacity, law enforcement, drugs, sovereign citizenry, and even handling burial arrangements for deceased prairie residents with no next-of-kin. As county administrator, Doon experiences it all firsthand.

No public lands

Beginning in the 1860s, Costilla County — a former Mexican land grant and Jicarilla Apache, Ute, and Diné homeland — was subdivided into real estate under William Gilpin. Each generation has brought new owners, new marketing — and new problems.

After the land was subdivided into the Costilla and Trinchera Estates, “it just kept getting subdivided, and subdivided,” Doon said. “A lot of it was your classic land speculation where you take a big, huge chunk of land and cut it up into little pieces and sell it off and try and make more money so that the sum of the parts is worth more than the whole.”

Like yesteryear, Costilla County remains divided into two geographic areas: the north and the south. Today, there are more housing units total in the southern half of the county, but slightly more population in the north.

Costilla County is 3,600 people, most of whom live in the small-town concentrations of San Luis, Blanca, and Fort Garland. Many smaller communities are scattered all the way from the first-wave riparian settlements in the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, west to the Rio Grande, with second-wave religious settlements dotting the prairie down to New Mexico.

[Related: Cheap Land | The Jaroso Legacy]

The fringes beyond the settlements, though long subdivided, remained vacant and alone. “It always seemed like wild, open space, and nothing was surveyed,” Doon said. “Nothing was fenced off. Since the seventies, there's been some people trying to make a living out there, but they often just last a couple of winters, or a few years, and then leave. It used to seem few and far between.”

A contemporary prairie settlement.

Today’s settlers

The third wave of settlement really began to take hold around 2008, Doon said.

“The first big wave of people coming I noticed in was in 2008, when there was a bad economic collapse,” Doon said. “Real estate values fell across the country, and there was a mortgage scandal. I started noticing people coming in because of the cheap land. It was still a place people could afford.”

“The next wave of people we saw was when marijuana became legal,” Doon said. “After the attraction of cheap land, everybody's dream now was they were going to move to Colorado, build their own greenhouse, and grow their own weed.”

"That was really when we saw a lot of stealing of water, big time,” Doon said. People were pumping straight from the Rio Grande, he said, and any other water source they could find. Water is universally scarce and over-adjudicated in the area, and a new era of water wars and bitter regard blossomed.

A Costilla County subdivision advertises land near a reservoir.

“It got really crazy,” Doon said. “It’s just because, if you Google ‘cheap land in Colorado,’ your first 50 listings are going to be stuff in this county.” Before the internet, “people had a harder time finding and being able to buy these properties,” Doon said.

Over 1,000 people now live in these outlying, off-grid, subdivided areas, with pocket communities and scatters of landowners throughout the county. Distant outlines of mid-progress architecture and vehicles now dot the landscape. “Here, the census may not be as accurate,” Doon acknowledged, as the outlying population leans toward underreporting.

Each year come spring, new builds sprout up. “No money down entices people,” Doon said. “They don’t research it at all. And it sure looks pretty on the Internet.”

Many arrive fresh from a confirmation email, and do not even realize a well and an alternative energy source are necessary. Others plan to live off-grid intentionally with nature and might disappear after the first sub-degree winter night — the harsh prairie valley is notoriously one of the coldest places in the nation. Some plan to retire here, or camp here — and some have built lives for decades, with large trees and beautiful homesteads forty minutes from the nearest gas station.

A distant contemporary build on the Flats.

Prairie residents suggest they are happier at arm’s length, accustomed to the fringes and often feeling marginalized by and from the greater communities that surround them. Some may be fleeing the economy, the law, social pressures, and themselves. Others live in scrappy shelters that defy code. A deep skepticism of government and authority paints the landscape, described recently by author Ted Conover in his novel, “Cheap Land Colorado.”

Building a homestead on an empty lot in Costilla County means paying land taxes, permitting a septic tank, obtaining other building permits, figuring out water use, and installing a fence to keep grazing cattle from wandering into your yard. Empty lots are frequently used as grazing areas, and residents routinely chase cattle off their property, or stir them from sleeping on local roads.

With no municipal water availability or water rights tied to these lands, locals take water from public or private sources, visit wells or springs, travel to fill large tanks, or pay for water services to come fill their tanks at home, Doon explained. Some who can afford to dig wells at varying lengths, and to varying success.

Failure to pay taxes means the property is repossessed and then sold on behalf of the county, The county contracts a sales company to sell the land online.

A prairie scene.

Out here, you are living with the elements, contending for space with creatures also trying to survive. During one visit to the prairie, Goat, a retired iron worker from Montana, showed off the remaining puffiness of his hand bit by a black widow. He had made the mistake of reaching into a toolbox without looking first.

But that is not what’s projected, and there have been many lawsuits stemming from the actual viability of living here.

“I've always had issues with the way realtors market the land,” Doon said. “It's very, very misleading.”

As a county representative, Doon himself picks up the tab on some of this false marketing. He finds himself personally managing residential expectations set forward by real estate companies who are nowhere to be found when things go south or are not as advertised.

A typical road on the prairie.

“One of the biggest things is just managing people's expectations,” Doon explained. “For example, people will buy property on roads that have not been adopted by the county.”

When roads are adopted by the County, they get state funding for maintenance, so there is no extra cost burden on the County, Doon said. However, the county has no responsibility to maintain roads that have not been built to county standards.

“Some subdivisions are homeowners associations, so they maintain their own roads,” Doon said. “Other subdivisions don't have functioning homeowner's association, so the roads absolutely don't get maintained.”

Doon said the county has over 1800 miles of total roads in its inventory, "Which for less than 4000 people, is crazy. But there are hundreds and hundreds of more miles of roads that are not under inventory,” Doon said.

A road in southern Costilla County.

And people who live on those roads have an expectation. “They come in and ask us, ‘When are you going to grade my road? When are you going to plow the snow? When are you going to bring power to my lawn? When are you going to put water and sewer systems into my lot?’ And the answer is ‘Never’ for all of those things.”

Doon said people get angry when they learn the limitations of the property they’ve purchased.

“Sometimes it's hard. Sometimes people are belligerent,” Doon said. “They tell us we don’t care. But other times it's sad. It’s an older person or a person with a special need who bought this property out there. And, you know, we don't have the financial resources to assist them.”

Doon said entitlement plays a huge role in how people perceive access to local resources. “Somehow people think that when they come in, they're entitled to all those amenities. Some of them come from more proper subdivisions, and more populated areas in different states. That's what they had wherever they left, so that’s what they expect to have where they’re going. And it's just not here.”

County offices are understaffed for the volume of calls and inquiries. Doon said there is no additional revenue, along with a much higher demand. “Clearly, there are way more people out here. Our number of building permits is way higher than it's ever been,” Doon said. “But we're not bringing in any more revenue. So that's where we're really stretched thin, is just having staff to process and monitor all this stuff. It keeps staff very busy — we just get so many calls.”

Doon said he estimates somewhere around 25% of new residents refuse to get septic or building permits “and make it really difficult. That that's our biggest personal challenge, is dealing with the land use aspect.”

A perception of inconsistency in land and building code enforcement is heard across the prairie. Doon said he thinks the Costilla County land use code “is, in my opinion, very basic things to follow. The one we really try to enforce the most is just having a septic system. You don't even need a well, but the septic system is the one we really, really try to enforce, because we feel like that's where a real public health and environmental health challenges can come along.”

Doon said the social atmosphere has also changed. Most locals are already untrusting and skeptical of outsiders, newcomers, strangers, or any combination thereof. Cultural and social barriers have unilaterally separated heritage families from relating to newer settlers on the prairie.

“In 1998, when I moved here, this was like Mayberry — literally,” Doon said. “The jail was a drunk tank with a key hanging on the wall and you could let yourself in and out. And without a doubt, that has radically changed. Now, the jail is constantly full of people we've never heard of.”

Doon said he once donated a pair of pants to a man who had a court hearing who was about his same size and appeared in rags.

The flat-landers include veterans of wars, and many have health issues and extremely limited access. People on disability and social security benefits scrape by with not a lot of extra room in the budget.

Abandoned lots.

Doon said the social services director “has the most challenging job in the county. All of this is also stressing our Department of Social Services. They've seen a huge spike in clients coming in, and with it, the need for public health, personal care providers, and more. And there's just no accompanying revenue to help us deal with this.”

Doon said the situations are often dire by the time the county is involved. “A couple years ago, we had a family trudge down the mountains through two feet of snow. They’d been living in a tent,” Doon said. “They were waving the white flag like, ‘Oh my God, we can't do this anymore.’”

An increase in people passing away on the prairie without next-of-kin — and sometimes, without an identity at all — has also forced the county to step up.

“If somebody passes away, and they have no next of kin, and no financial resources, the state statue actually names the coroner and the county administrator as being responsible for the burial,” Doon said.

It’s not fine print Doon realized existed when he took the county administrator job in 2011. Now, when he gets a call from the county coroner’s office, “I just think, ‘Oh, no.’” Doon said.

“The first one I ever had to do, really kind of struck me,” he said. “That lady was there for about seven days. Her body was so decomposed, the coroner needed serious help."

“I won't say I am jaded, but, you know, I've gotten a little bit used to it,” Doon said. “That first one really kind of kind of shook me to my soul a little bit, especially because I was in the person’s home, and I just didn’t know what to do.”

Doon also arranges for caskets and burials. “One of [the deceased] was recently a veteran, and we asked the VFW and the Legion to come and do a ceremony,” he said. They were able to procure some money for a tombstone for the veteran, Doon said, and held a small makeshift service. “But it’s just so sad, you know, having those situations come up.”

Prairie residents say they have known of many people passing away on the prairie. Faulty buildings, fire systems, smoke inhalation, collapsed roofs, frostbite and freezing to death are not uncommon. Sometimes folks lack the materials, resources, or preparedness to survive.

“As soon as these people die, anything of value on their property gets stolen,” Doon said.

To combat increased theft, and to deal with jail capacity issues, the county recently passed a $0.01 sales tax increase. “It’s specifically for public safety and law enforcement, and to hopefully build a new jail someday,” Doon said. He said the need is obvious in the community. “We've put that on the ballot a few times and it's failed. And I don't think we did anything different this time.”

Costilla County, pictured bottom, direct center, has almost no public lands. Map courtesy Colorado State Forest Service.

Public lands

Another byproduct of so many subdivisions is a lack of public lands, Doon said, all tied back to the purchase of the original Sangre de Cristo Land Grant. Since the privatization of the land grant in 1864, the county remains about 97% privately owned. (And that number was 99% until recent years.)

“We never had an initial opportunity to get federal lands, because everything was at first deeded to an individual,” Doon said. "The greenbelt areas that were made were few and far between.”

Doon talks about obtaining a balance of public lands. “They have the opposite problem in Mineral County, which is 97% federal land,” Doon said. “And that sort of hurts them. Opportunities for growth are restricted because there's so little private land. I feel like having more of a mix and a balance is ideal for a lot of reasons.”

The biggest challenge right now, Doon said, is keeping up. “We're just trying to keep staff together who can deal with all these issues, and try and pay them enough money to stay,” Doon said. “If you look at the big picture in Colorado, we're the outlier. Other places are so more populated and have so much more money, and they have the real estate lobby. Our voice just doesn't go very far when it comes to lobbying for state legislation,” Doon said. “We're just not that heard.”

Kate Perdoni is a Senior Regional Producer with Rocky Mountain PBS and can be reached at kateperdoni@rmpbs.org.