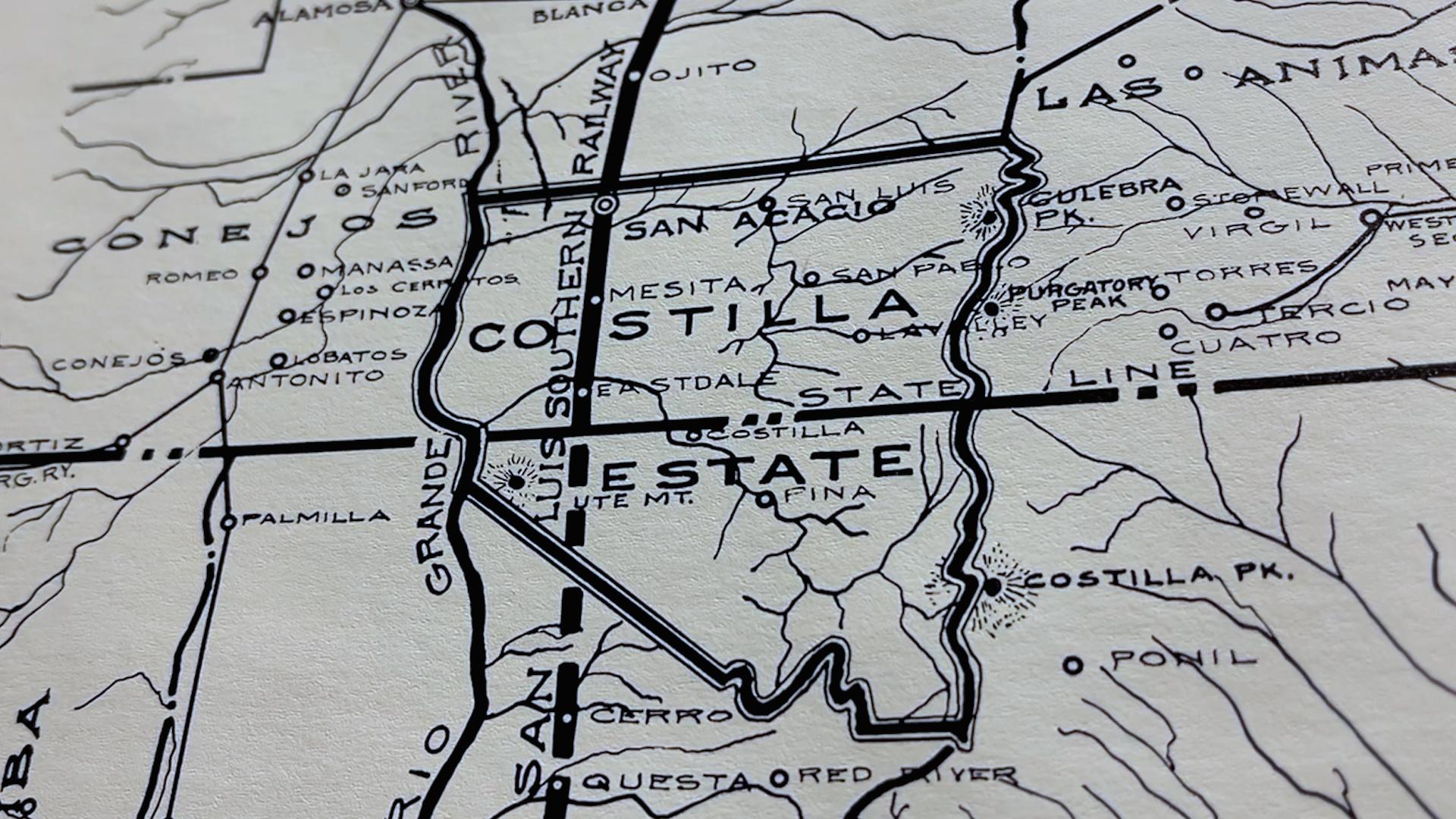

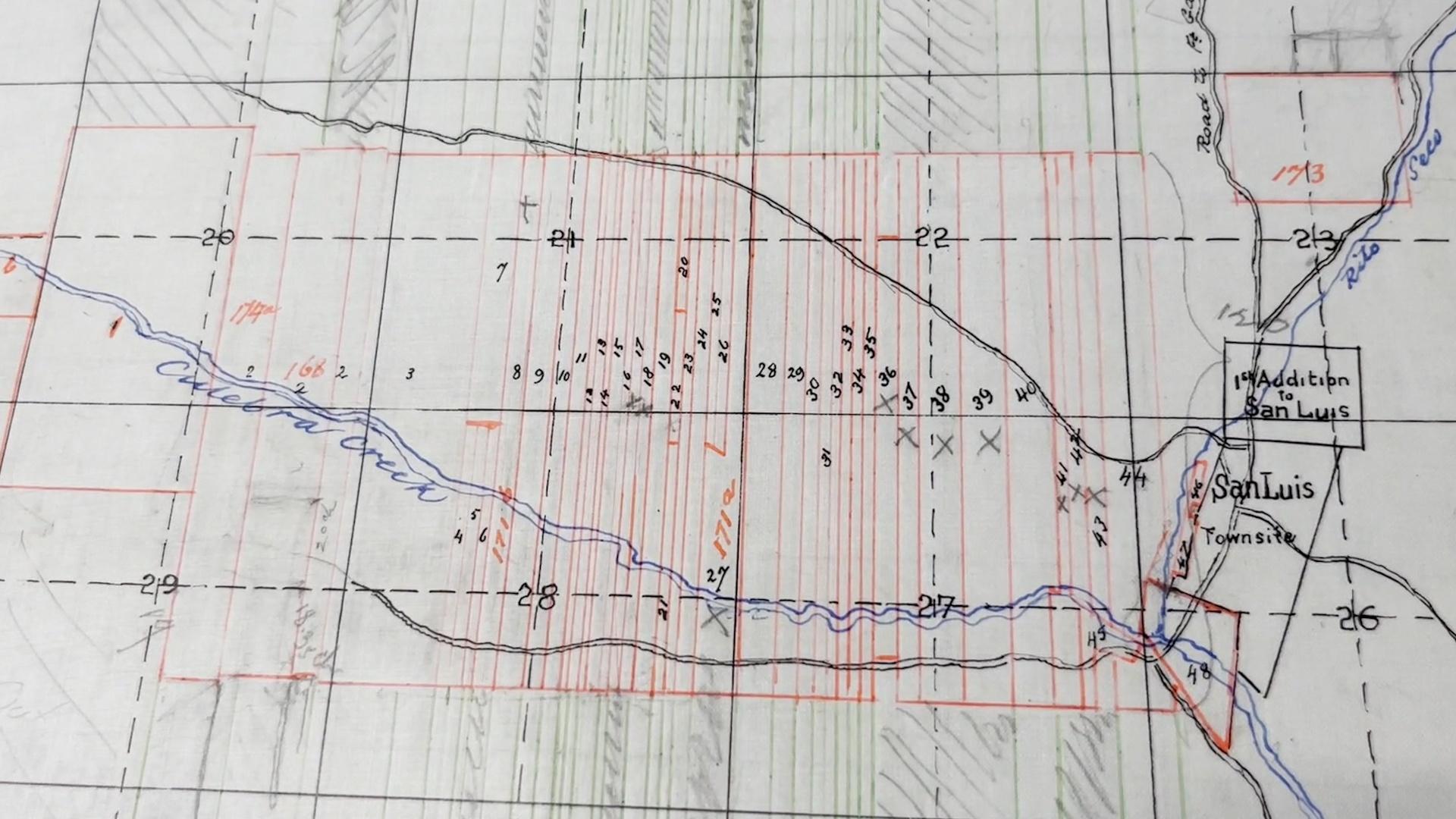

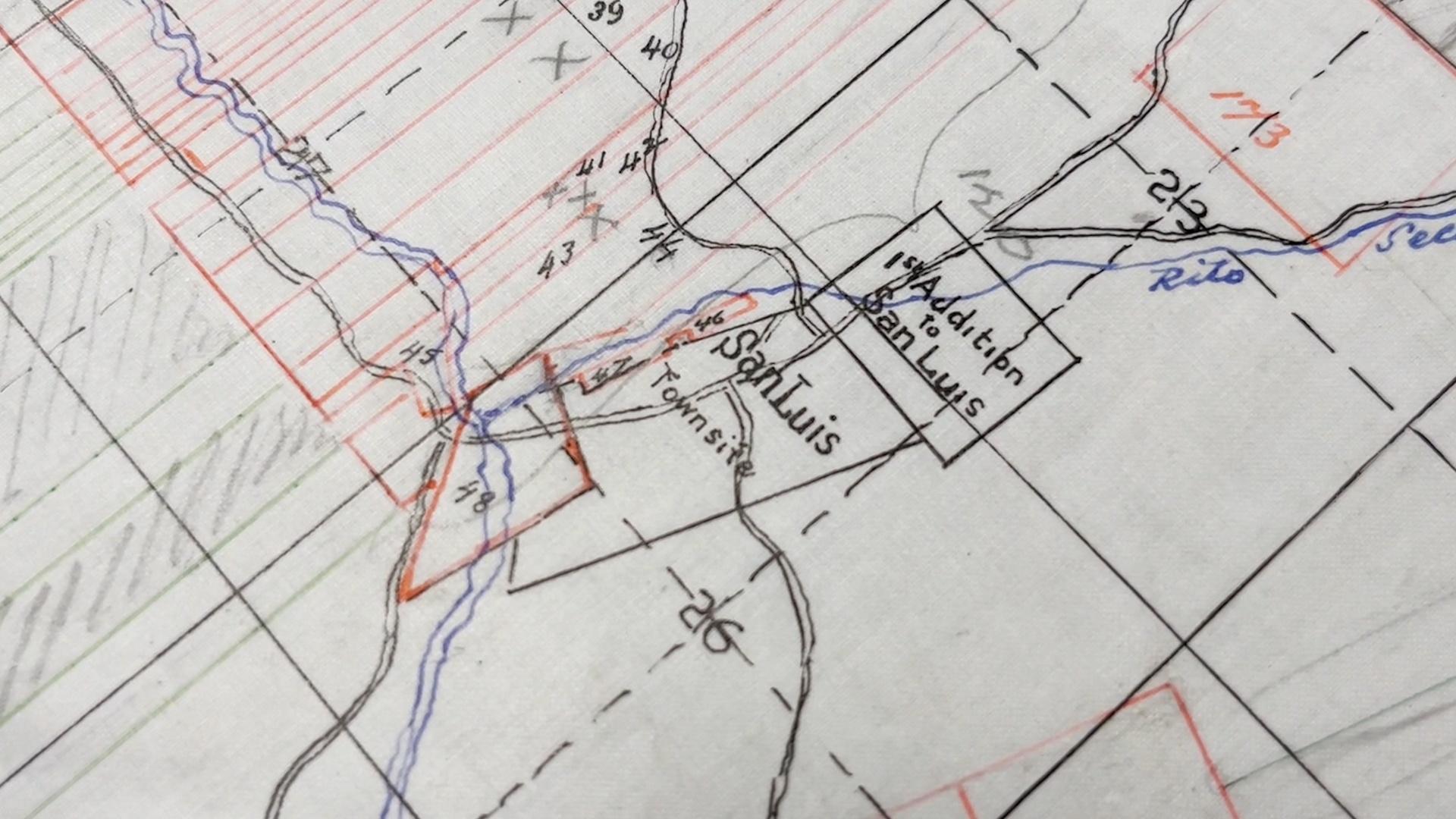

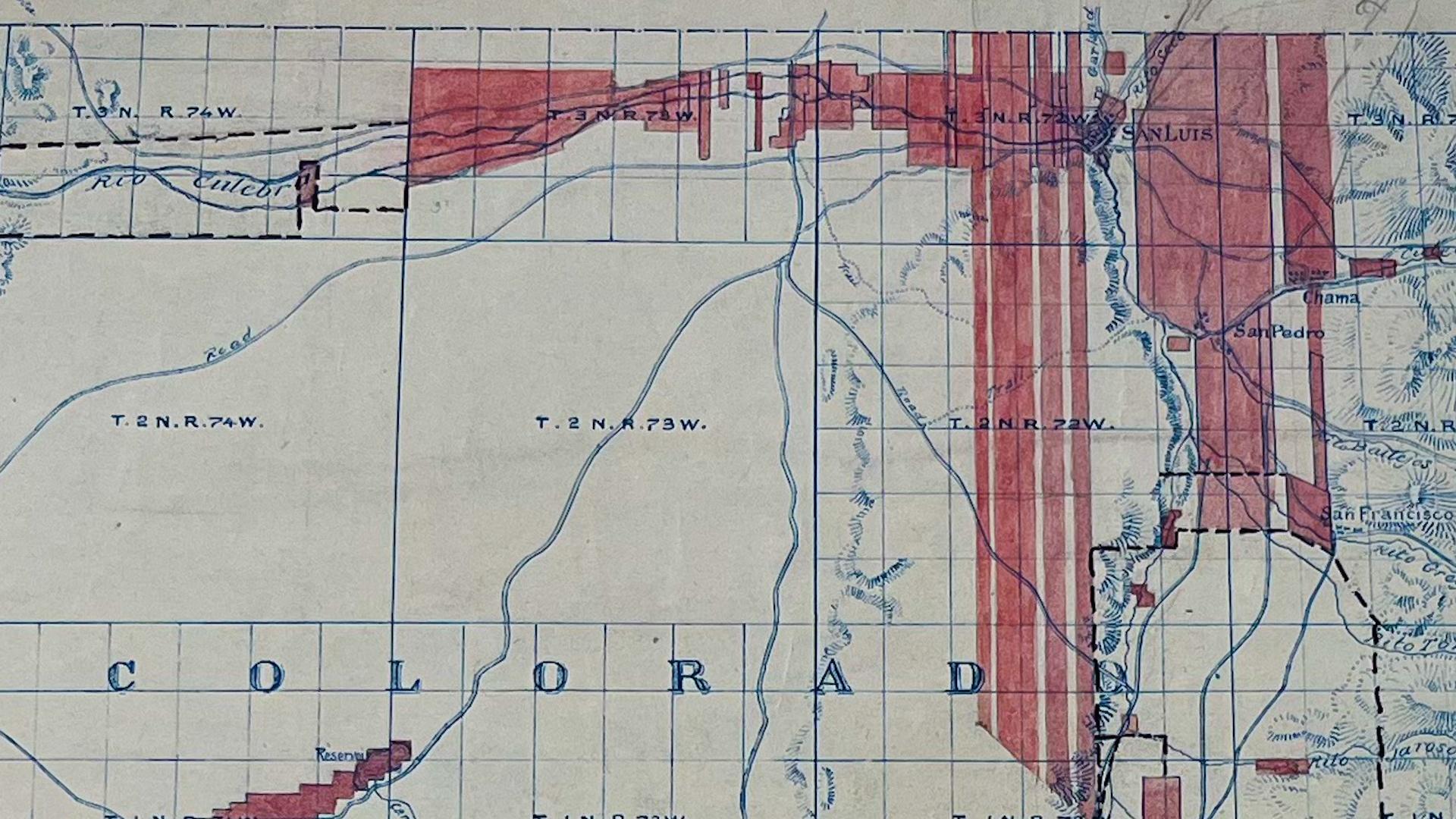

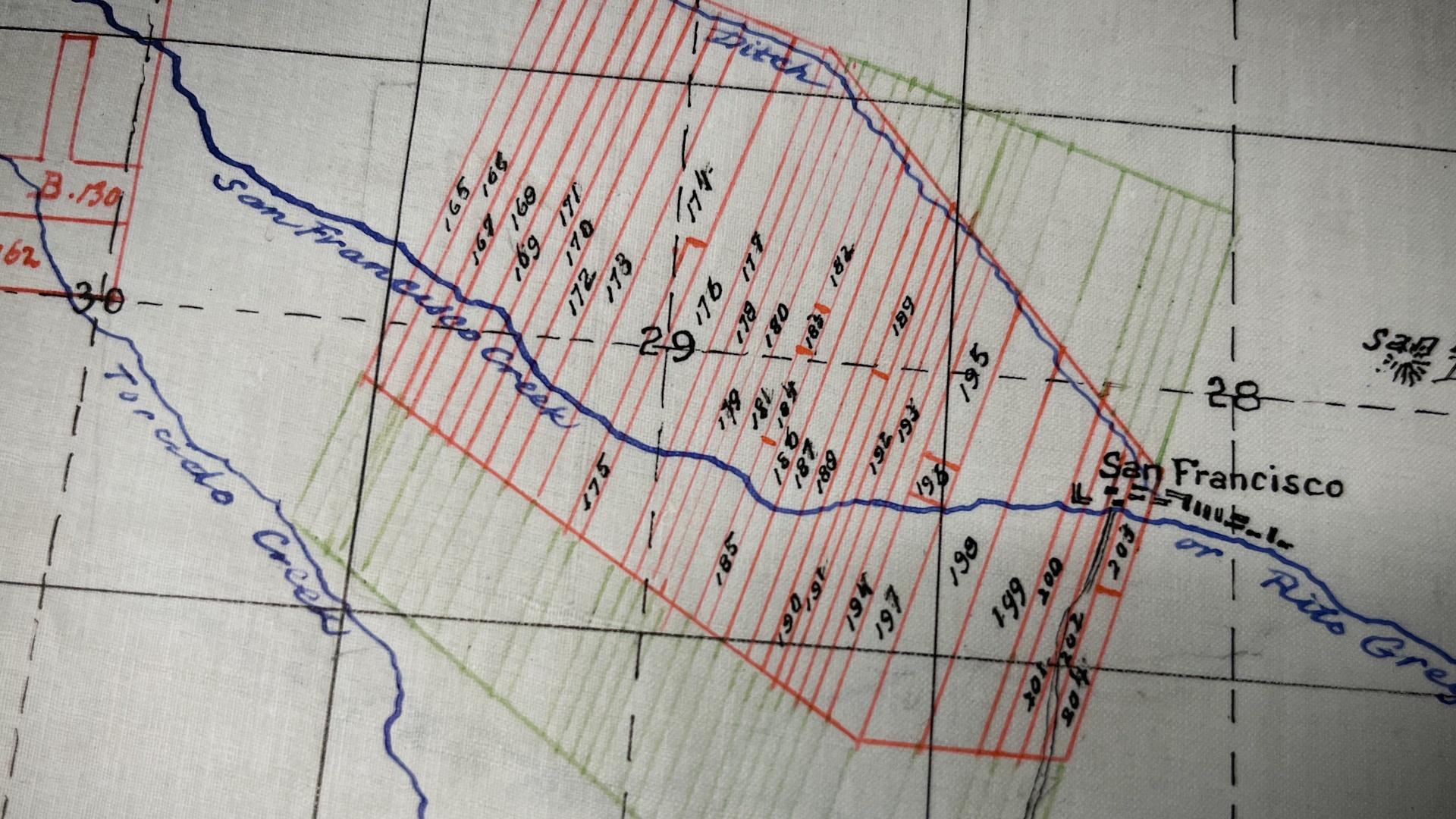

“This land was settled in the Spanish tradition of dividing land into long vara strips, also called long lots, or extenciones, as part of the settlement pattern, instead of using the PLSS,” explained Nystrom. “Vara lots were drawn perpendicular to a stream. They would extend miles in both directions to include not just the lowland areas, but further into the foothills so other types of terrain and ecosystems would be included, all in a long strip. They allowed equal physical access to the water source — it's one of a kind."

[Related: Watch a presentation about Culebra Watershed history by Joel Nystrom of Colorado Open Lands]

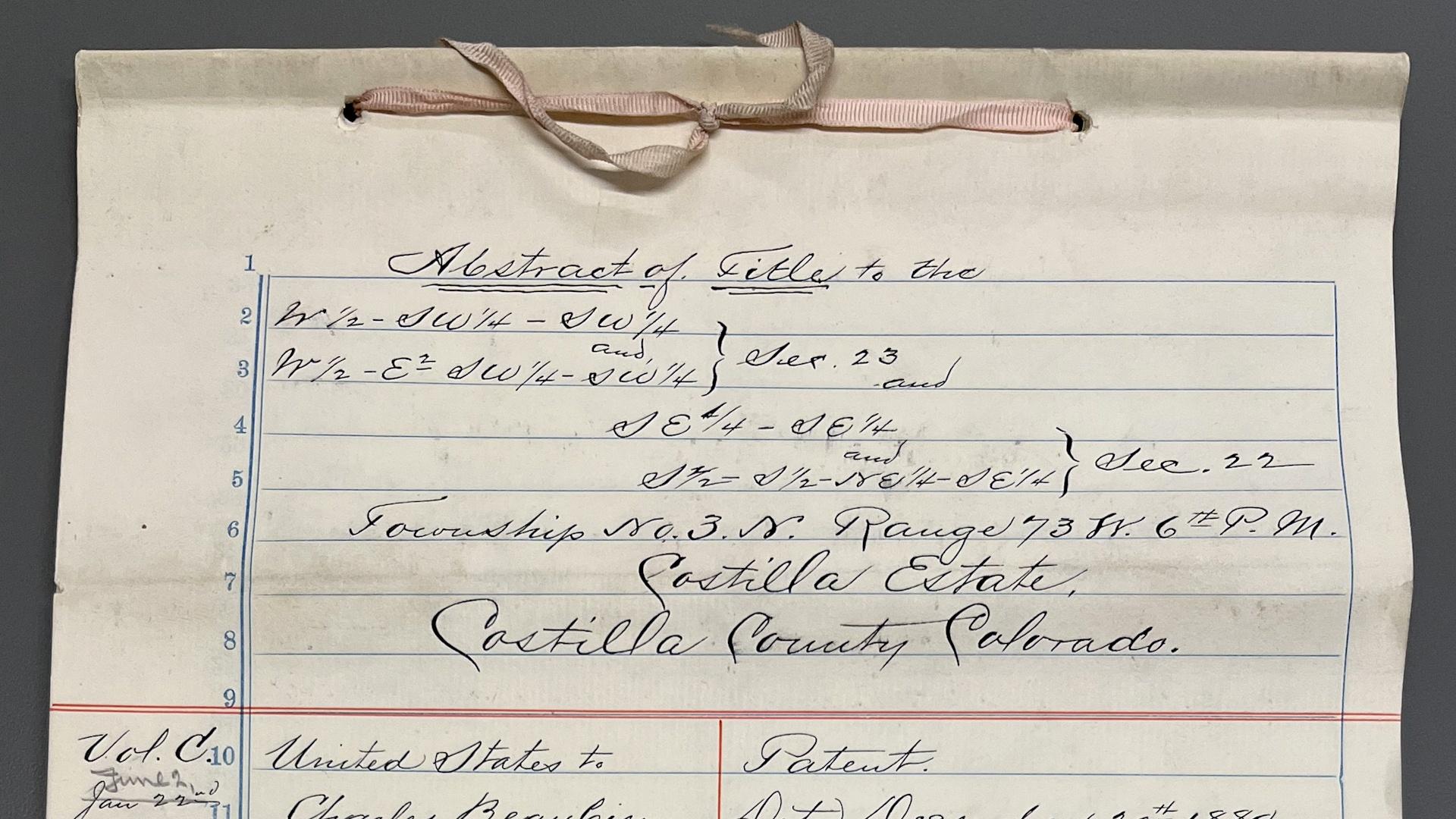

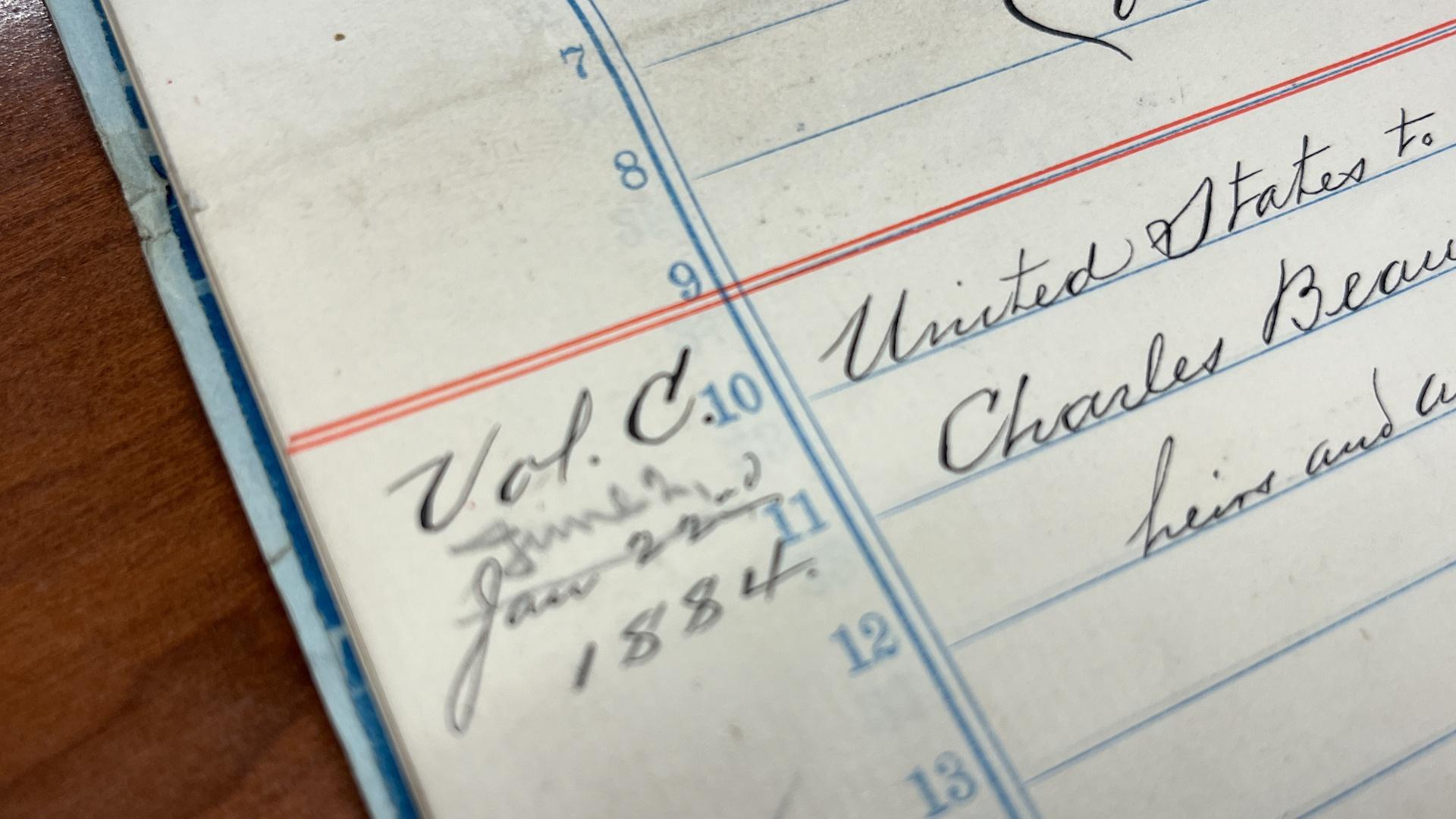

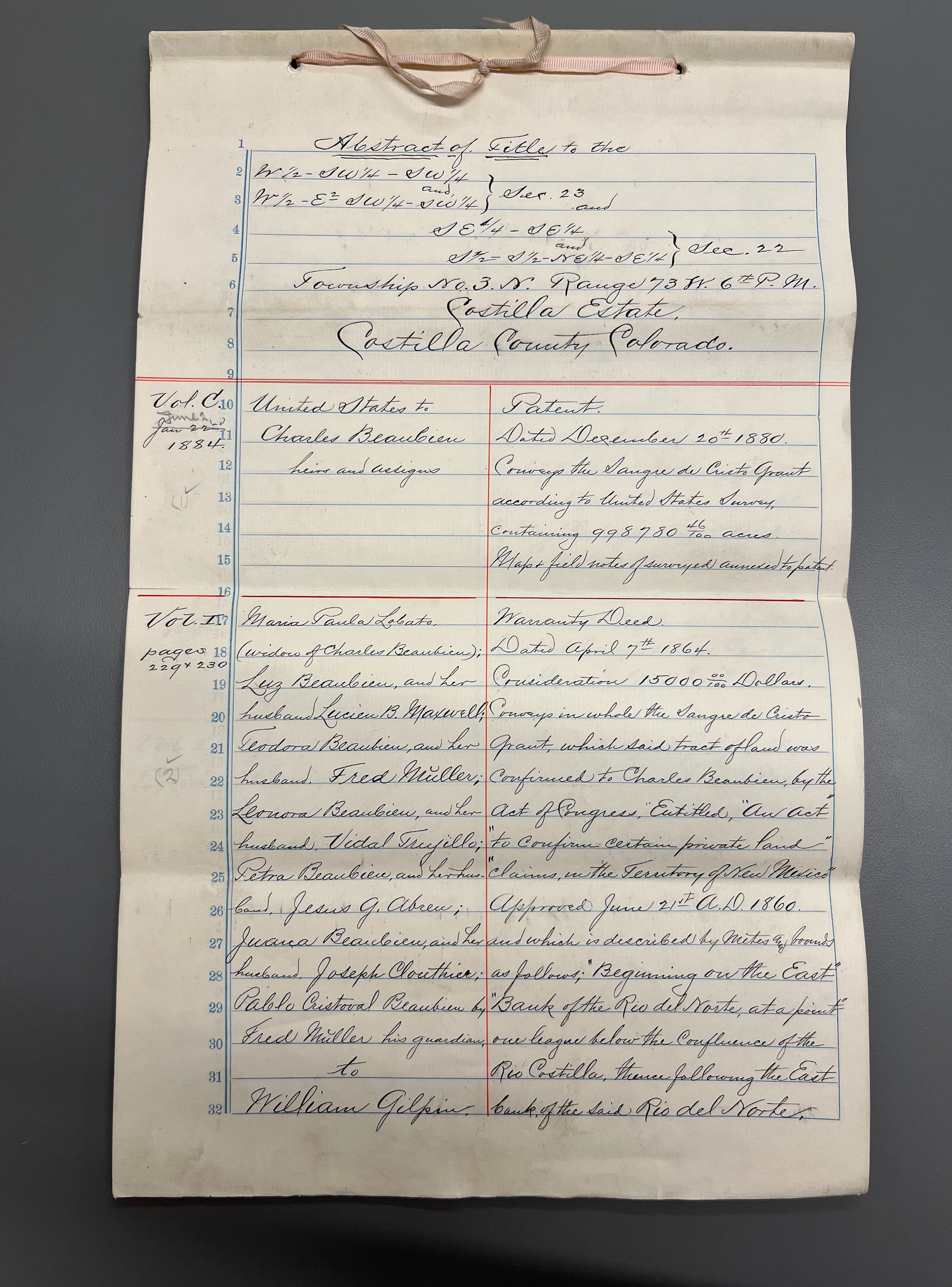

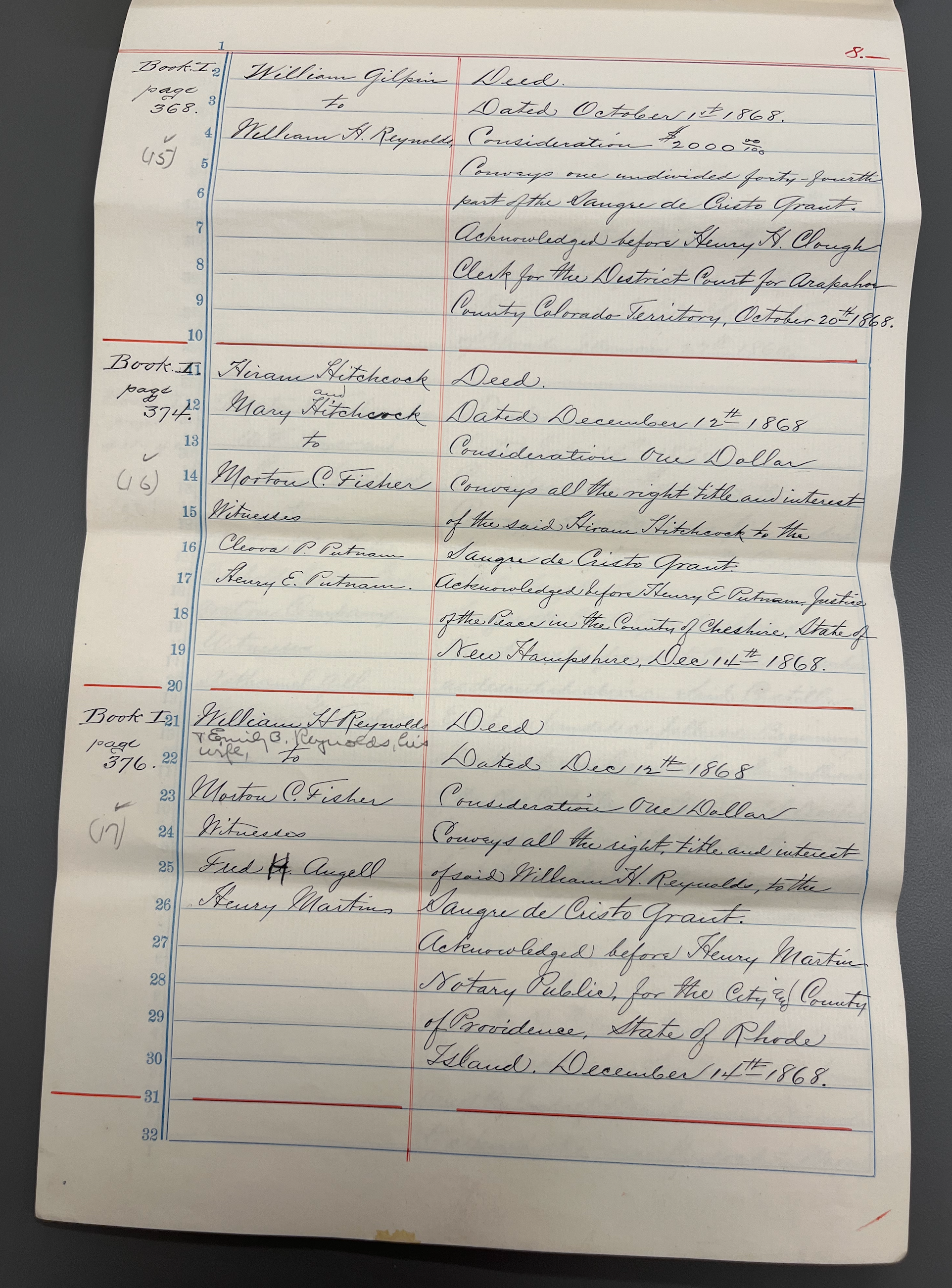

But vara strips went on seemingly forever, some for miles, stretching from the mountains of the east to the mesas of the south and severely limiting potential sales. Costilla Estates carved out new land measurements over top of the lengthy varas, creating odd-shaped parcels of land that fell into neither system.

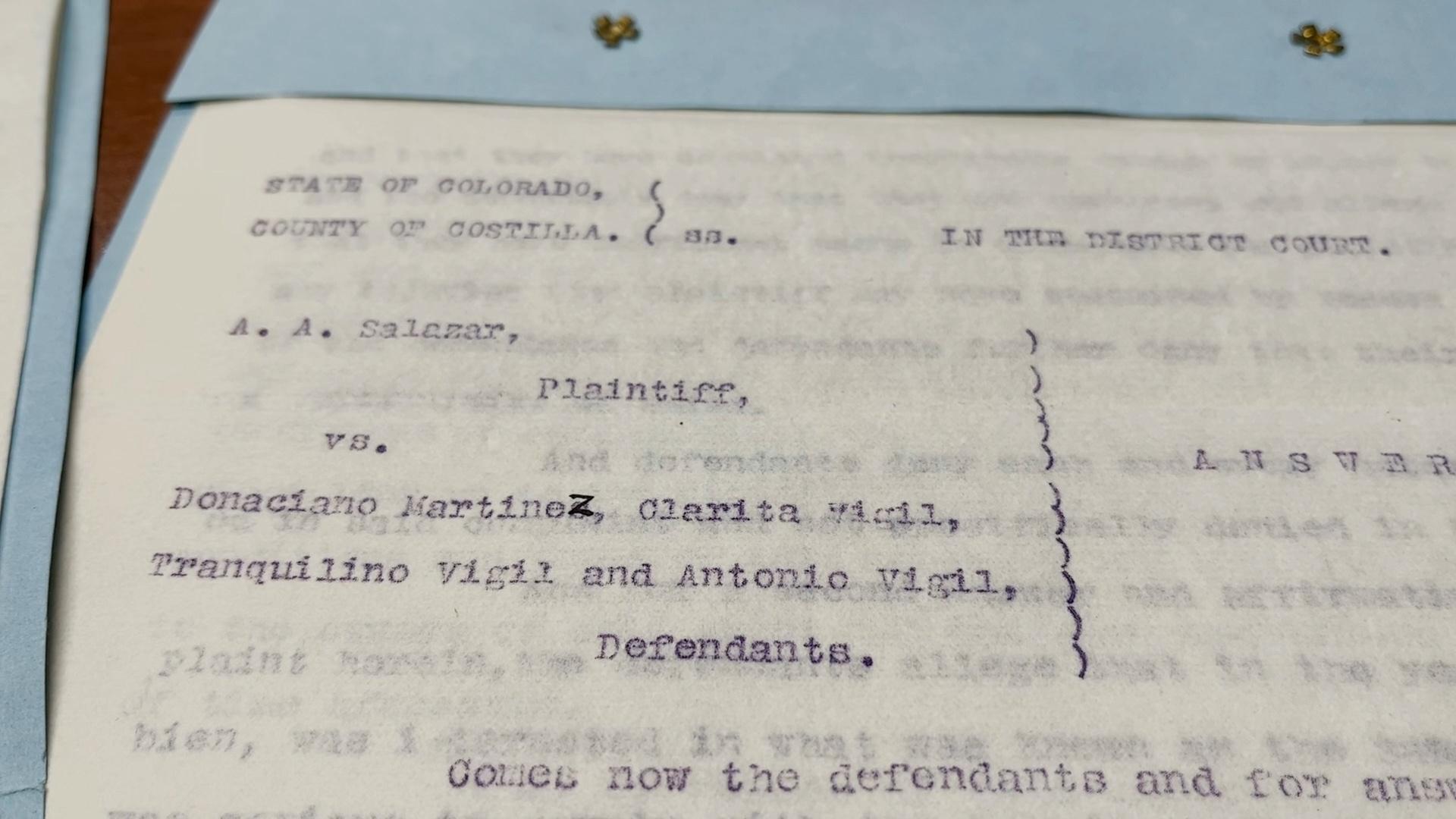

In the 2022 Costilla County court case Cielo Vista Ranch v. Mondragon, both vara boundary discrepancies and property destruction were addressed when a judge decided in favor of Cielo Vista Ranch, the private hiking, hunting, and fishing operation that exists on a portion of the former land grant.

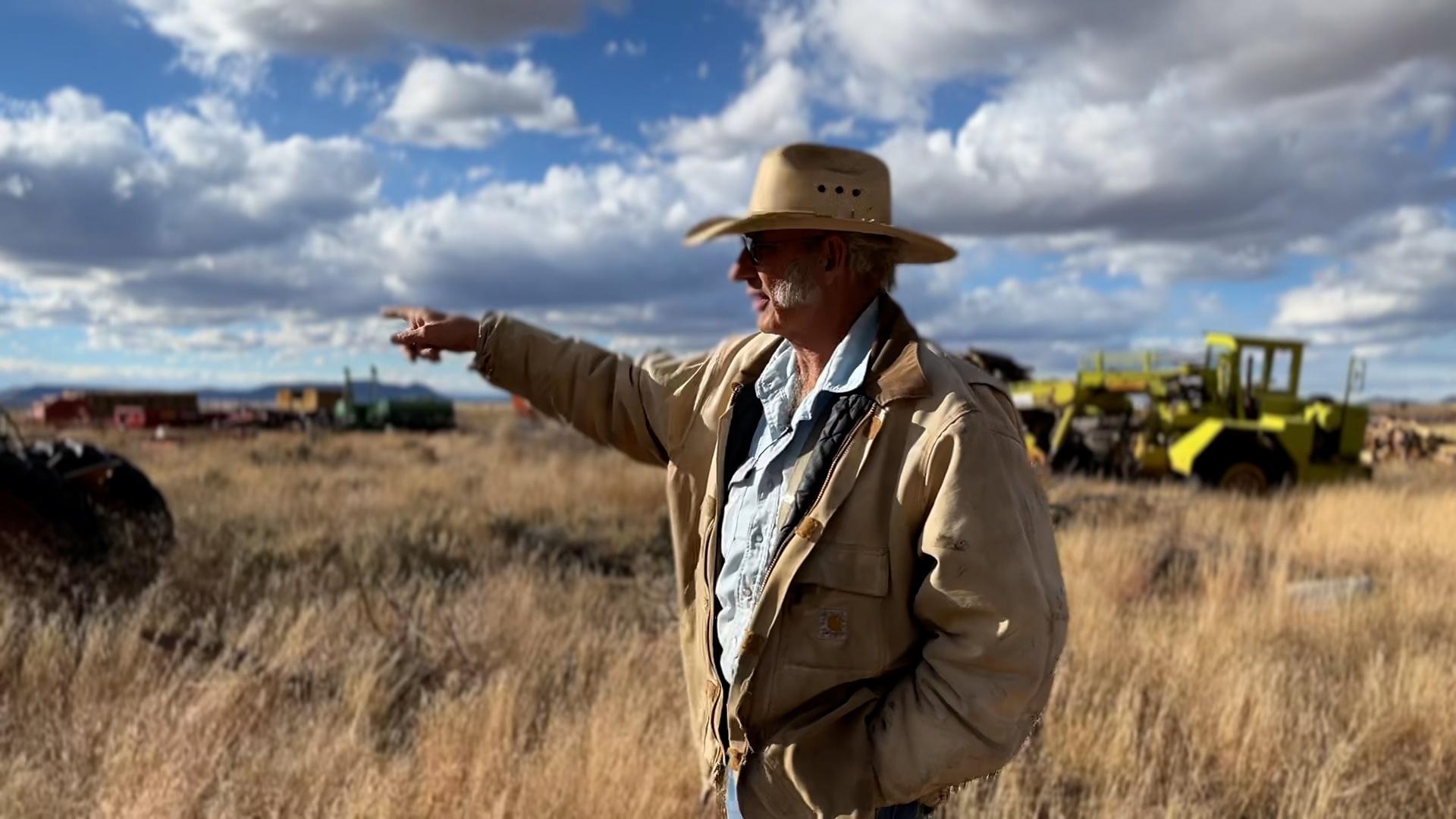

The case presented that while visiting his late father’s vara southeast of San Luis in a foothills agricultural area, Anthony Mondragon arrived to see a ten-foot-tall fence construed by Cielo Vista Ranch. Mondragon testified that he had always known this fenced land to be his family’s. The contested area of 1.4 acres was part of his father’s extencione. A non-irrigated foot hill, the area was typically used as an intermittent pasture between the ranch and common grazing lands.

San Luis has a complicated relationship with fences. It was a property fence that fueled the 1960’s range war resulting in Lobato v. Taylor, when a former owner first fenced locals from the mountains. When Mondragon saw the property fence on what he believed to be his family’s property, he and two friends worked with machinery to dismantle it and tear it down.

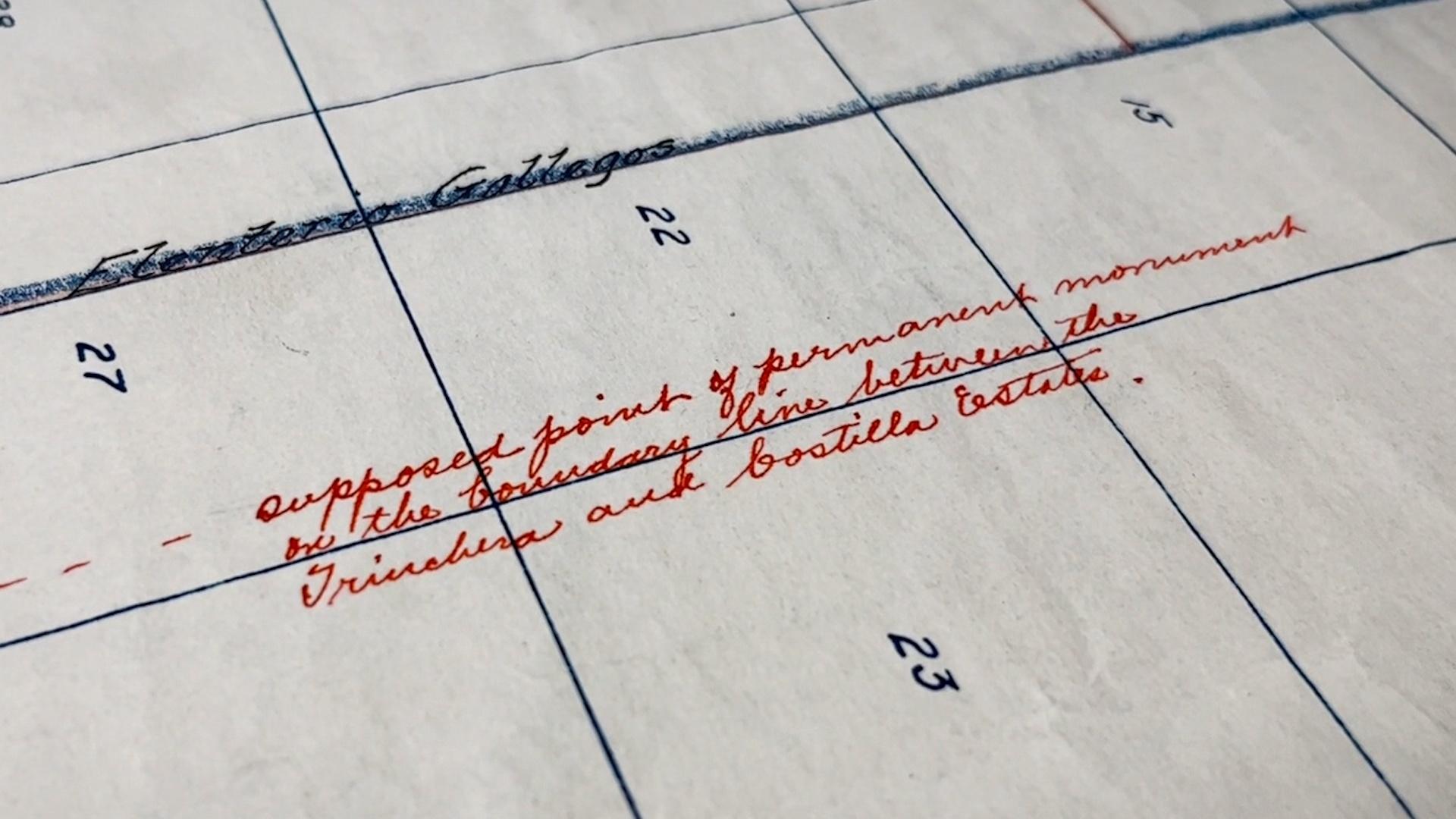

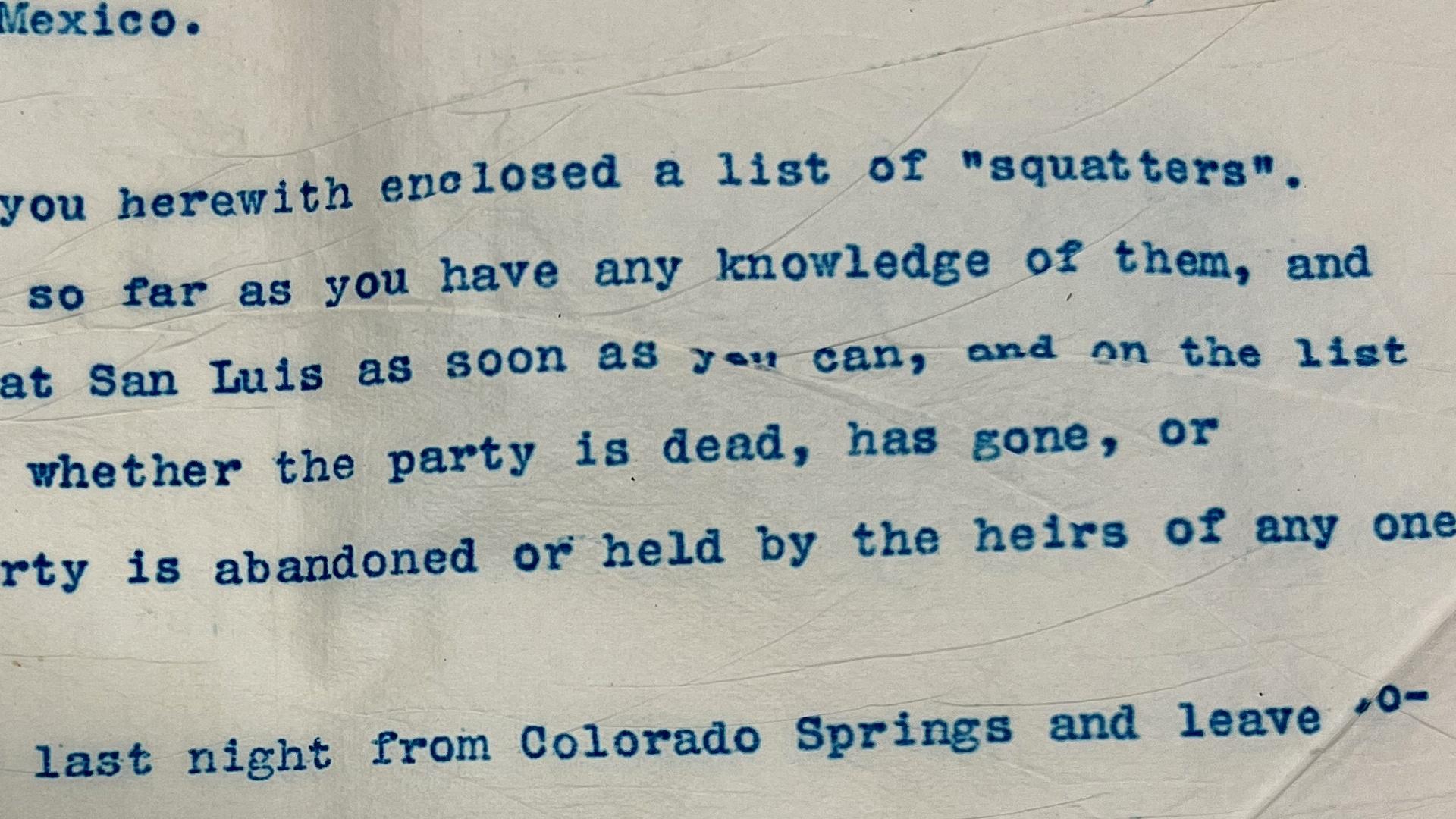

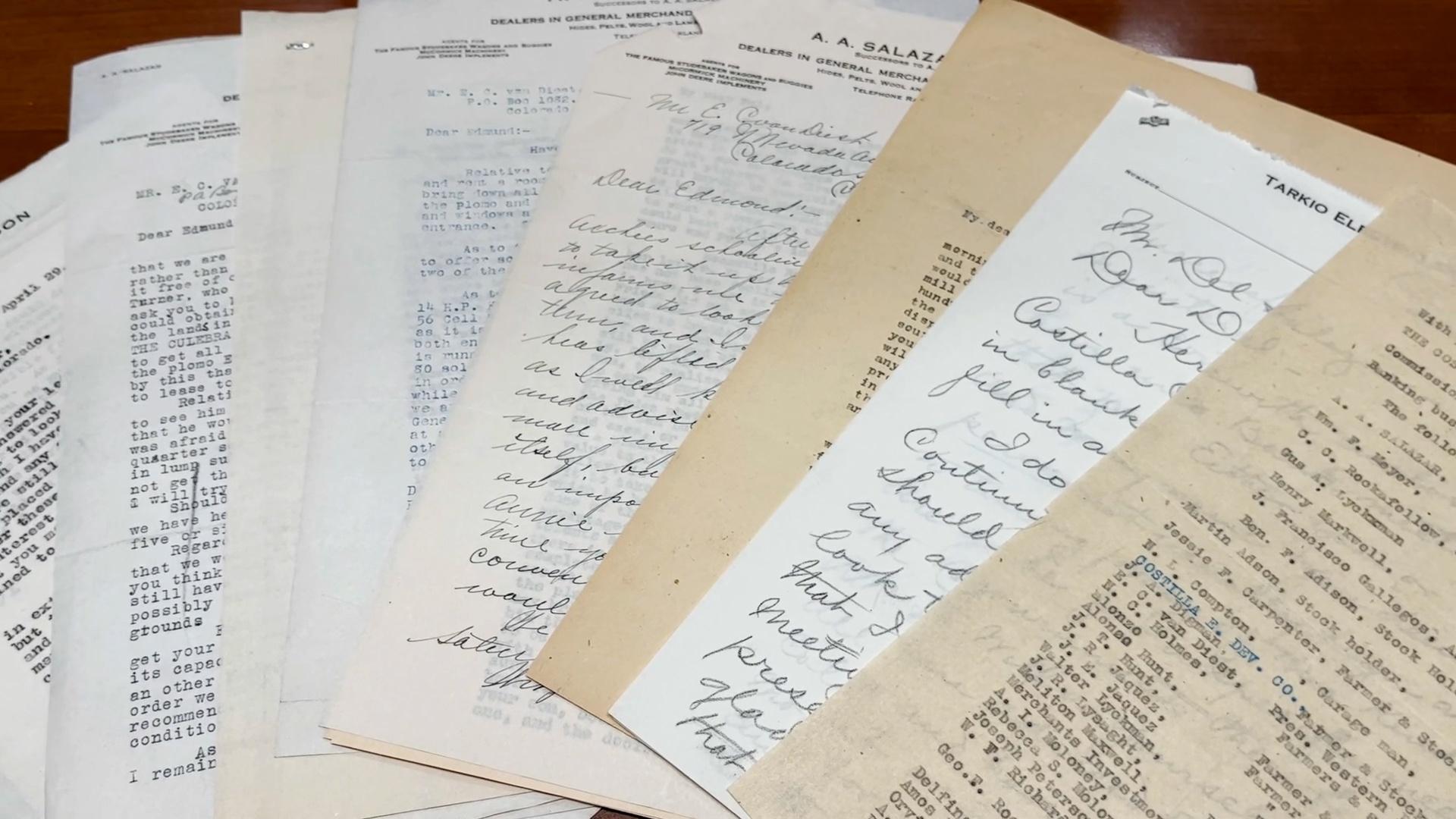

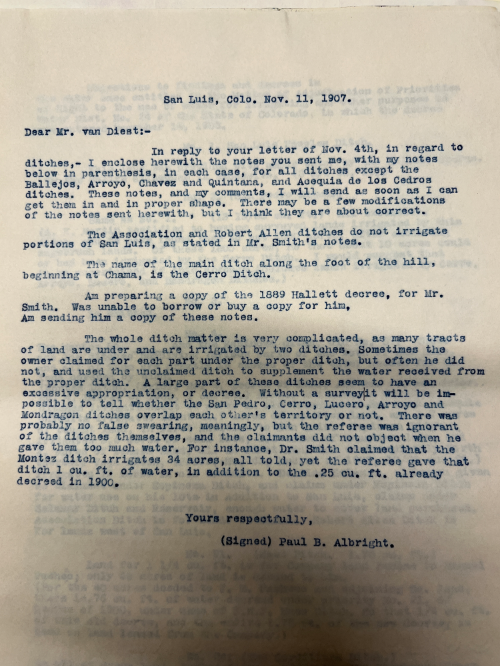

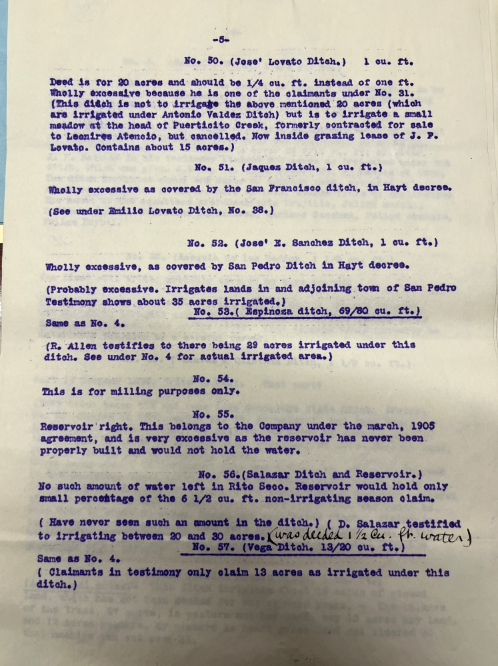

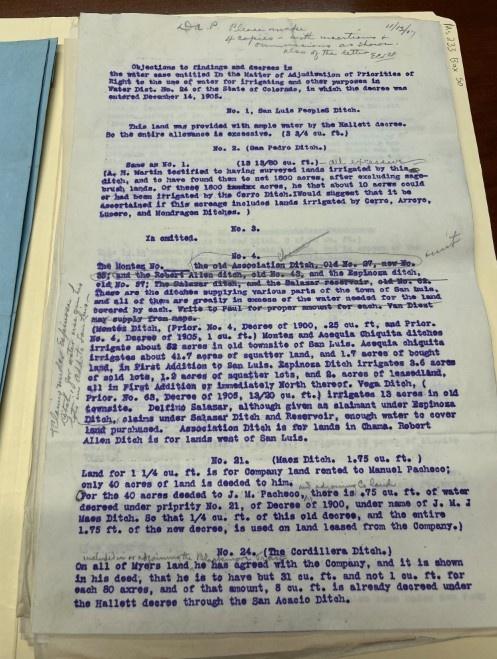

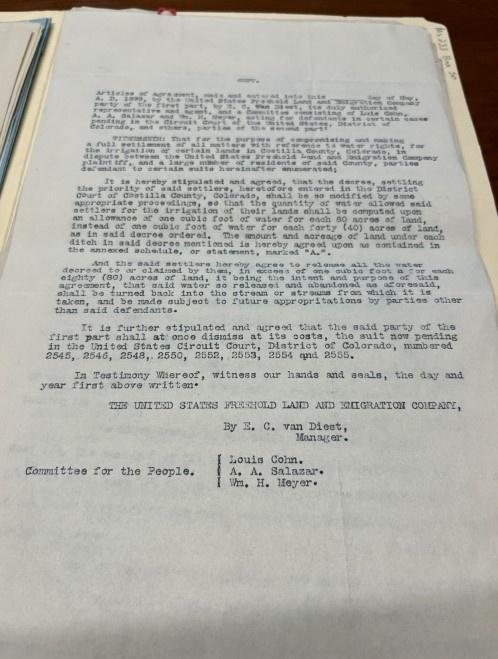

Central to this case were surveillance images of the fence removal taken by the ranch’s security cameras — and the initial Costilla Estate maps and documents of Edmond van Diest, circa 1896. But there was little acknowledgment of the traditional land system upon which the original discrepancy derived. Van Diest’s own defining boundary point of extenciones was entered as evidence. In the eyes of the then-Estate, the meandering midway point between Vallejos and San Francisco Creeks was considered the cutoff to the extenciones.

Though van Diest’s pen touched every land parcel in the county, his feet did not; and the extenciones had been long contested in court, for more than a century. Admittedly, the land boundary might follow neither vara nor PLSS. But without further survey, the judge ruled in favor of the ranch.