MESITA, Colo. — “Give us one free miracle,” Paonia-born lecturer Terence McKenna was fond of chiding his audiences, “and we’ll take it from there.”

McKenna’s statement was a tongue-in-check reference to science’s launch point from the Big Bang Theory — the notion that everything came from nothing in a single moment, with no prior indication. (He regarded this concept personally as “the limit case for credulity.”)

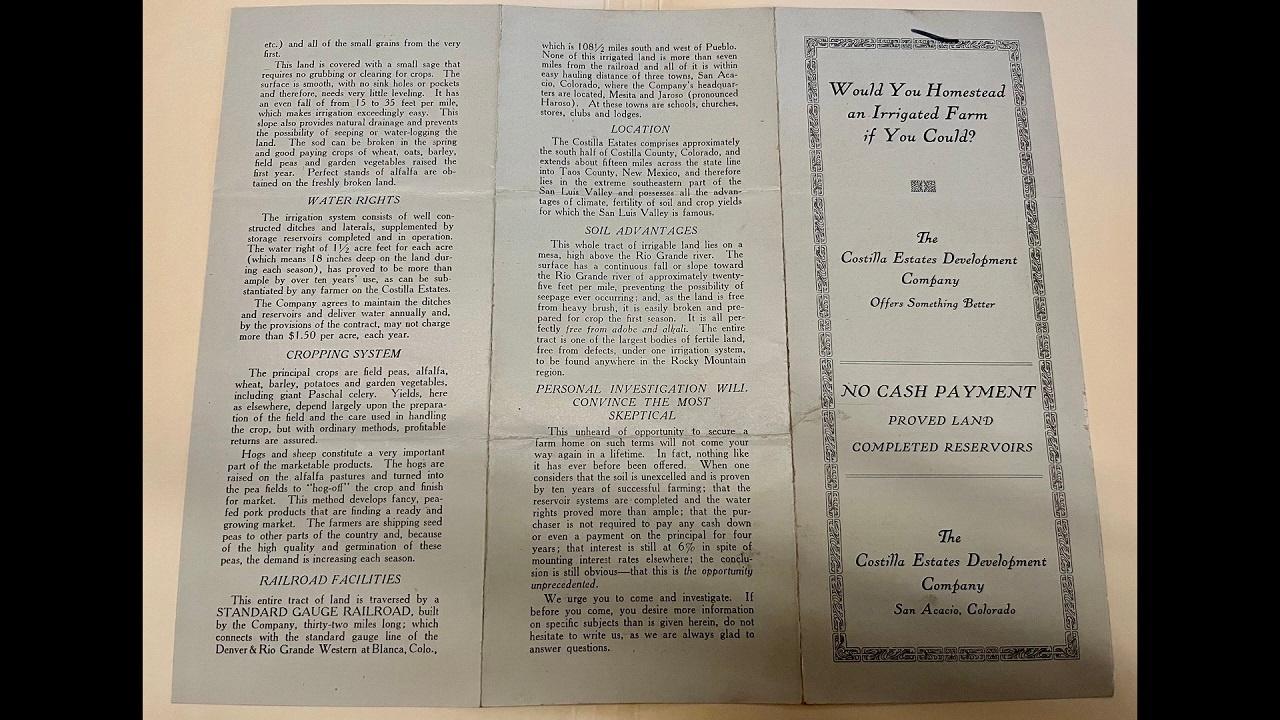

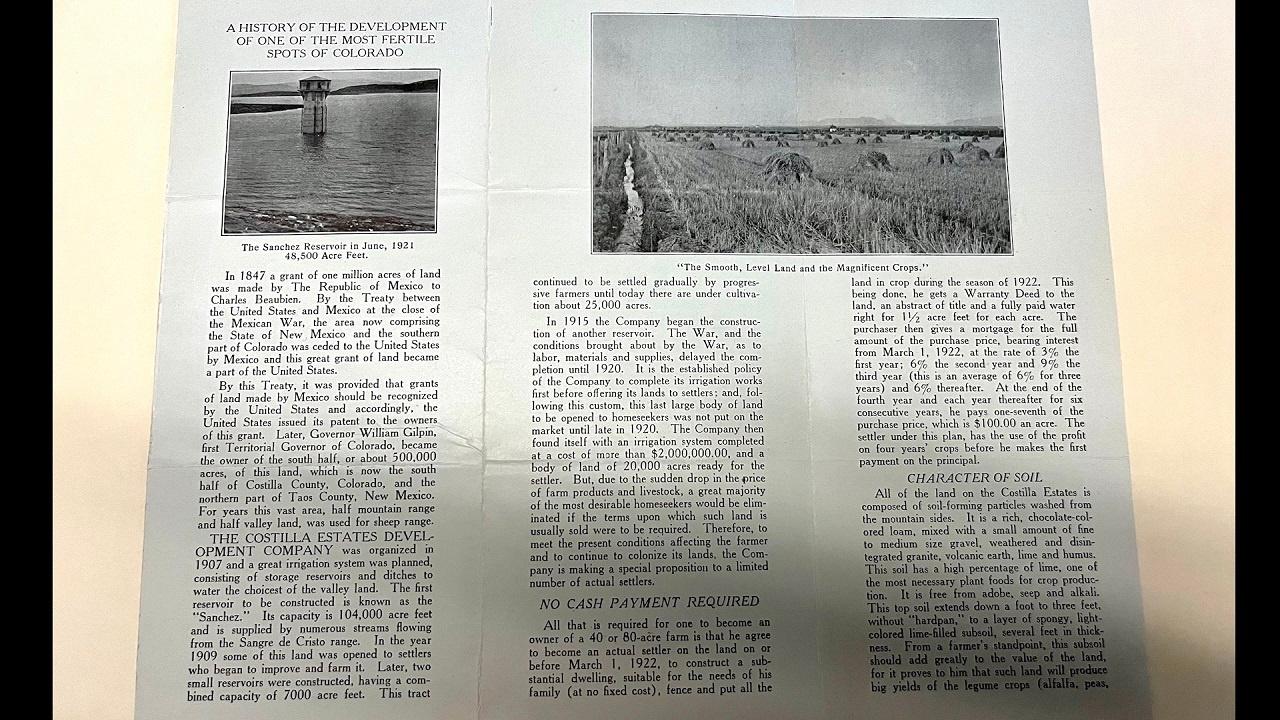

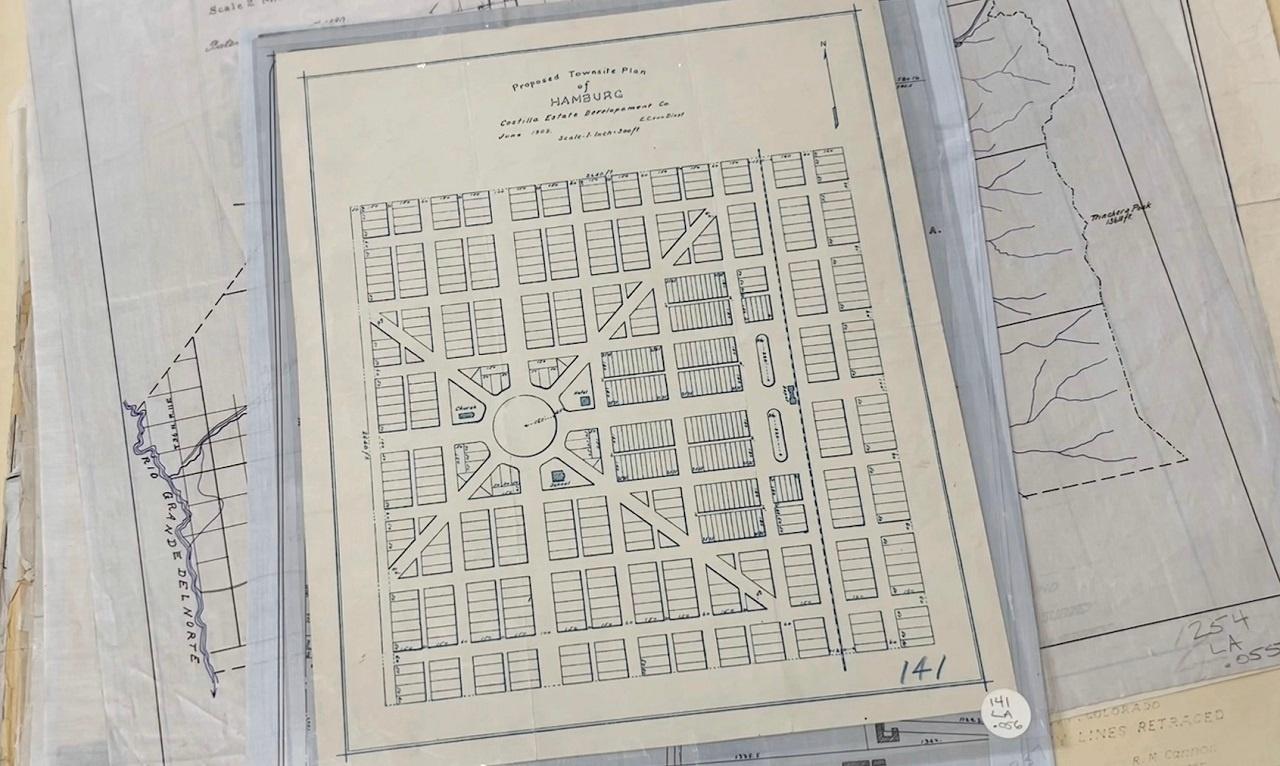

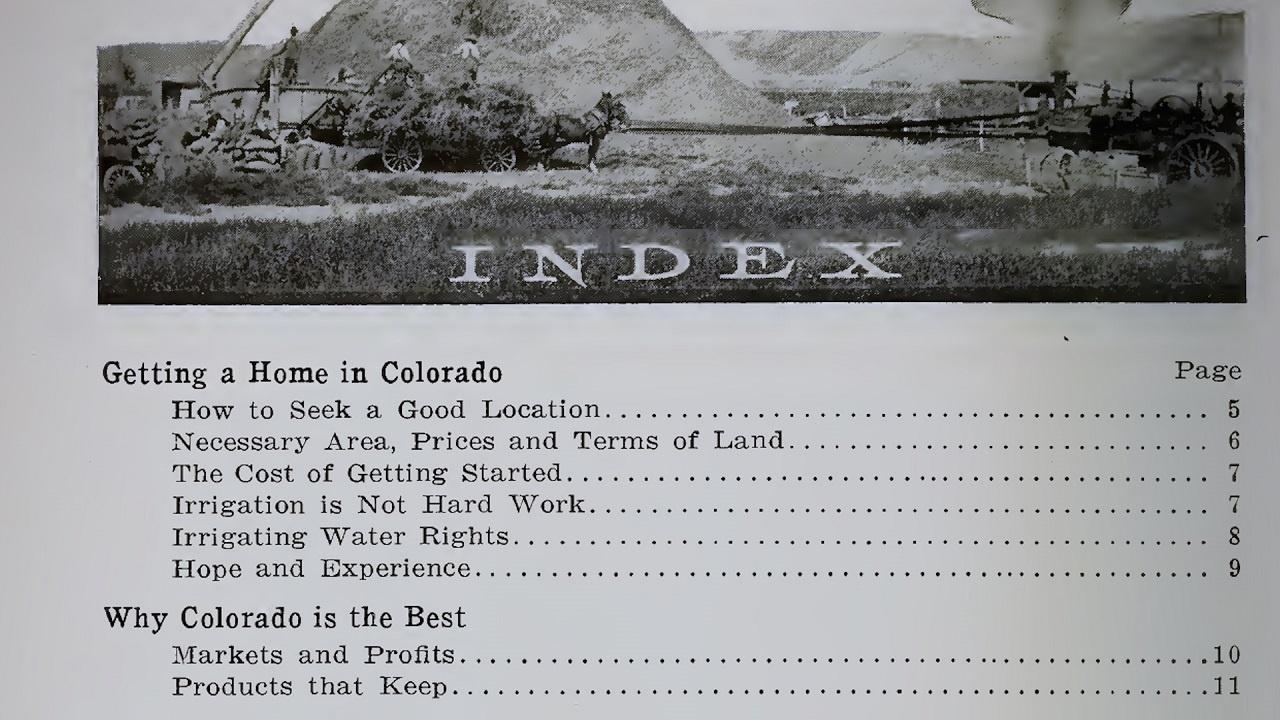

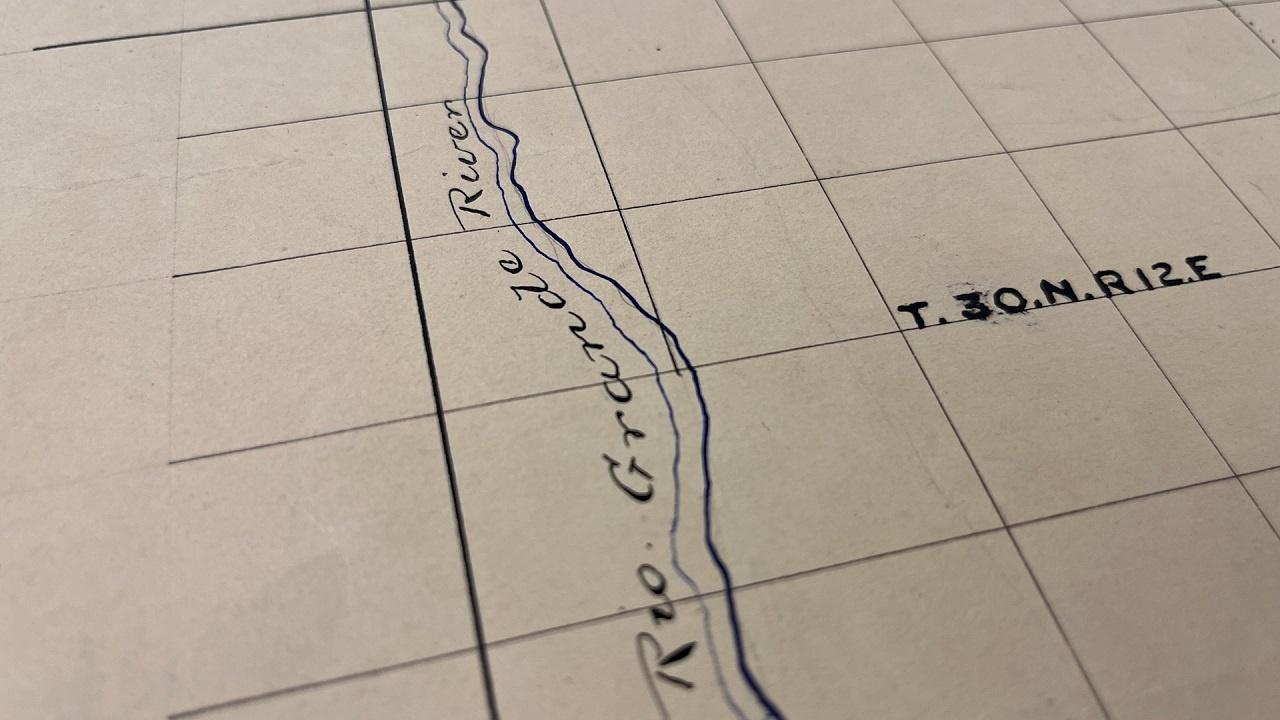

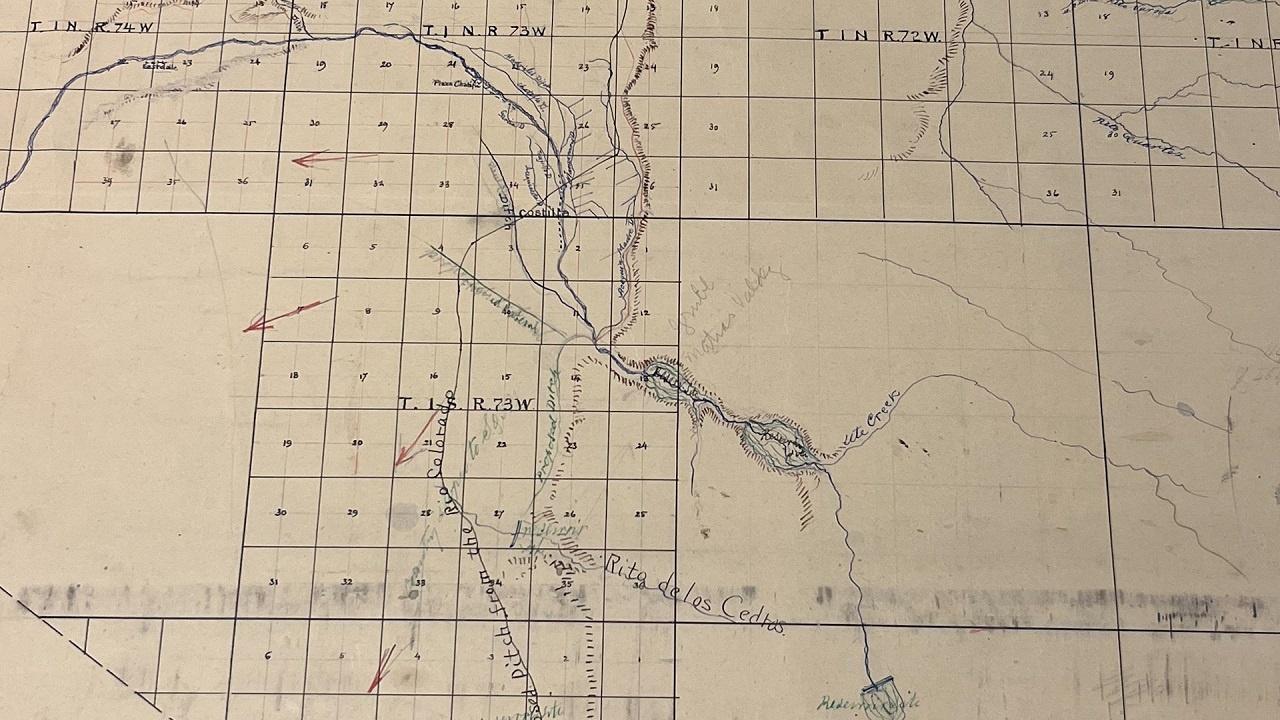

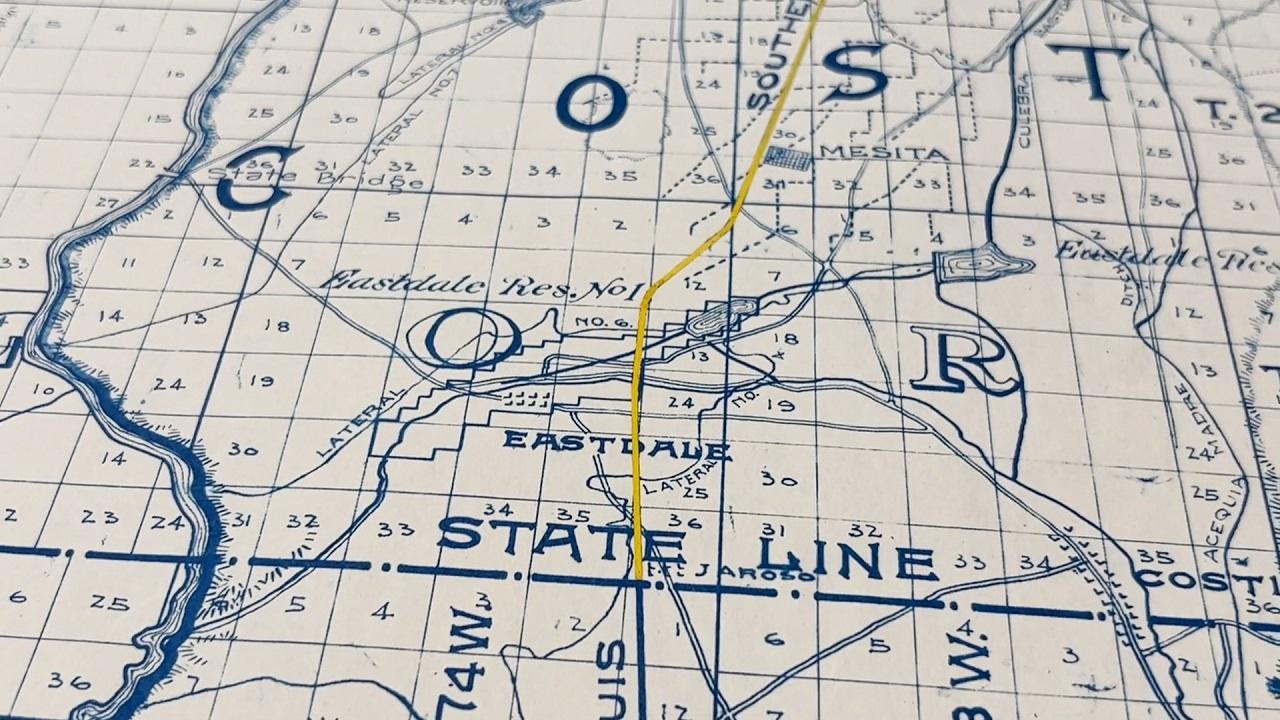

In the high desert of Costilla County, Colorado’s first settlements linger in a steady decrescendo from the eastern riparian foothills west to the Rio Grande. A sparse population still resides in this shadow of dreams, scattered across near-ghost towns among sage and prairie outlined by empty, loosely paved roads.

The “one free miracle” here?

Water.