'Trust and hope': The Aurora street outreach team's most important resources

AURORA, Colo. — “I'm a hope dealer, not a dope dealer.”

It’s a mantra that Erin Kay doesn’t take credit for coming up with, but it is one she lives her life by now. Kay is a part of the Mile High Behavioral Healthcare’s street outreach team in Aurora, which acts as a bridge between those without stable housing and services that could help them back on their feet.

Stationed at the Aurora Day Resource Center, two colorful vans that can seat at least a dozen people wait to drive through the streets of Aurora. Operating Tuesday through Friday and sometimes Saturdays, the two teams of two workers load up the vans with supplies like water, snacks, informational pamphlets and more for the people they hope to reach that day.

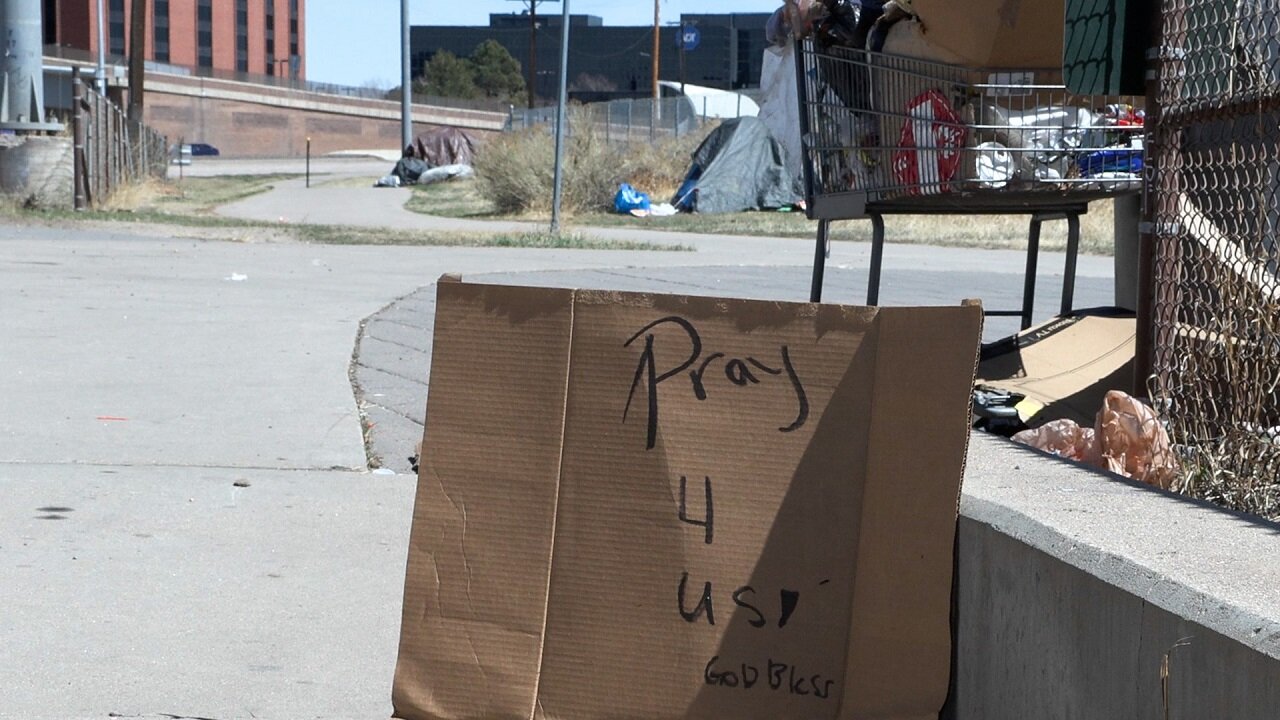

On Thursday, March 31 Rocky Mountain PBS accompanied Kay and her coworker for the morning's drive. The outreach team starts with a list of locations of possible encampments that people have reported through the city’s website. On this day, the first stop was a new report of tents near a baseball field.

As the team approached the tents, they brought supplies and called out to see if anyone was inside. Two people were there but unfortunately were sick and didn’t want to leave their tent. One person also said they were in need of a way to receive new identification, a problem that Aurora Day Resource Center can help with. While their illness prevented them from coming to the center that same day, Kay was able to exchange phone numbers with them so she could check on the individual in a couple of days.

“I really just try to connect with them and let them know, ‘Hey, somebody cares,’” said Kay. She knows first-hand what it is like to feel hopeless; she lived on the streets of Austin, Texas for about 10 years in her teens and early twenties. Kay was able to transition into a life with stable housing and responded by trying to help others who are now where she once was.

“There's a level of connection that really helps as far as being a peer and kind of having the proof is in the pudding with there is life after this experience,” she said.

After the first stop on Thursday, the team buckled back up in the van to visit another reported encampment. This time, the people who were living there weren’t home. Kay's team said this is common on nice, warm weather days. Still, the team left some supplies and information and planned to come by again to try again to connect in-person with those living there. The team did meet a friend of those living at these tents who also doesn't have permanent housing. So, they connected with him to find out where he was staying and planned to go to that location later to check on him again.

“There are small things that we can do for each other to make sure that everybody's successful,” explained Kay. “And if we do it together, we go a lot further for a lot longer period than if we just … left [people] to their own devices.”

The final stop of the morning route led the team to a location where they couldn’t find any tents or signs someone was living there. The team lead of volunteers and street outreach, Jason Goertz, said this is also part of the job. Oftentimes, he said, people either report the wrong location or the people who were staying there have moved on. While it didn’t happen when Rocky Mountain PBS was with the outreach team, Goertz said there are also times when people don’t want to talk to the team.

“I would say 80% of the time people are willing to engage with us in some capacity, eventually,” said Goertz, adding that it sometimes takes a while and some rapport-building to connect with someone, though they never stop trying. “Because I've never met a single person that doesn't want a safe place to be where they won't be bothered.”

Goertz has been with the organization since 2017, starting out on the street outreach team first.

“Most simply, I believe people deserve dignity no matter what,” he said as to the reason why he started in this job and what keeps him coming back to work every day.

“Our street outreach is really important to all citizens of Aurora. This is the mobile team. This is the team that is able to go there and connect with people at the most — at the rawest — at the most basic level,” said Goertz.

Aurora is one of the largest cities in the state, both in population and geographical area. And unlike Denver's downtown, for example, Aurora does not have one significant central location. This makes those who are living in the city without a home difficult to get to locations where they can find help.

“How it looks downtown is going to look different because you have a lot of stuff that can be condensed and you have a lot of resources,” said Goertz. But he continued to point out that Aurora’s suburban landscape changes how people do outreach, which for Mile High Behavioral Resource Center, means bringing the information and resources to the people by van.

“I like to think of us as a trampoline. You’ve got to get on the trampoline in order for it to work. But I'll be with you there every single time and say, ‘Hey, come on, jump with me,’” said Goertz.

The street outreach team also plays an important role for the abatements of camps. They work closely with the city — which also provides a significant amount funding for the nonprofit — and arrive before those hired to remove the camp. The street outreach team offers shelter to the people living in the camps, as well as other supportive resources. The idea is to build relationships, something Goertz said is the key to ending homelessness.

“I like to say the most important resources that we have to give are trust and hope,” said Goertz. “They are the hardest to get. They are the easiest to lose, but they are essential for ending homelessness.”

The street outreach team will see a new impact to their work. On Monday, March 28, Aurora City Council passed an ordinance that will ban encampments on public or private property in the city. The ordinance will require at least a 72-hour notice before an encampment. It will take effect in a few weeks.

[Related: Study shows the impact of encampment sweeps on Denver's unhoused population]

“It's definitely going to impact us. It can't not impact us,” said Goertz. “We are a service provider and so whether there is a camping ban or not, our goal is to try to connect with people experiencing homelessness regardless of their circumstances, regardless of what they're going through.”

The camping ban didn’t pass through City Council without objections. Council member Crystal Murillo called it a "flawed policy" during debate before that final vote.

"The idea that the solution to ending homelessness isn't housing surprises me," said Murillo. "When I think about what is compassionate and how we treat people with dignity and respect, it's not forcing people to abandon a place they have chosen to survive."

Other council members disagreed, saying it would be the opposite of compassionate to not force people out of the encampments.

"I think what we're doing is trying to help those who are in encampments to get out of that situation by having to offer alternative shelter for them. And obviously, you know, if we can help them with drug addiction, with mental health issues that is way more compassionate than leaving them in an encampment that is not sanitary ... that is not safe for them let alone our business and our residents that live near those," said Françoise Bergan, the mayor pro tempore.

The vote came down to a tie, which Aurora Mayor Mike Coffman broke by voting in favor the ban. Coffman has been an outspoken advocate for a camping ban in the city since posing as an unhoused person for a week in January 2021. He previously proposed a camping ban measure which failed last August in a tied vote.

Goertz didn’t elaborate on the street outreach team’s position on the ban, but said they will continue to work closely with the city and those who are unhoused. He did recognize that many people in the Denver metro area have seen more people who appear to be without stable housing in recent years.

“It has increased. But I would like to say the biggest thing is it's also really increased visibility,” said Goertz.

Last August, the Metro Denver Homeless Initiative (MDHI) published a point-in-time survey to determine how many people are experiencing homelessness in the seven-county Denver area. The report found on a single day in February 2021, there was an increase of 40% of people who were staying in emergency shelters compared to the year before. The report also found the overall increase in sheltered homelessness rose 22% year over year.

Right now, the Mile High Behavioral Health Center operates the only permanent overnight shelter in the city of Aurora, the Comitis Crisis Center. During the debates over the camping ban, council members went back and forth on how many beds could be put into the shelter at one time. Mile High Behavioral Health Center said for the last couple of years, during cold nights, they could only fit 75 people. Outside of COVID-19 times, there was hearsay among council members that the shelter could fit 175 people.

Regardless of capacity, to truly solve homelessness, Goertz reiterated to Rocky Mountain PBS that you must build relationships with people. He encourages anyone who wants to help to contact him and volunteer: “Come in and be a part of this,” he said.

As a person who was once living unhoused and is now part of the street outreach team in Aurora, Kay agrees with the same philosophy on homelessness — meet people and just understand they are human too.

“If you come to somebody and you meet them as a person experiencing homelessness, that's not the end of their story; that is not the end of what they are able to impact in the world,” said Kay. “A lot of these folks I work with on a regular basis are great people; they're amazing people. They just need a little bit of help.”

Amanda Horvath is the managing producer at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at amandahorvath@rmpbs.org.

Brian Willie is the content production manager at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach him at brianwillie@rmpbs.org.