Reading laterally with Palmer High School’s Mr. Blakesley

COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. — When many people think of high school social studies, they think of dusty textbooks, dull documentaries and extensive research papers.

But in Paul Blakesley’s Palmer High School 9th grade social studies classes, students analyze Instagram posts, tweets and the occasional TikTok.

Blakesley is incorporating modern media into his freshman U.S. government courses to underline the importance of media literacy and to train more attuned media consumers.

“Every source has a perspective, so how do you know what that perspective is?” said Blakesley. “That’s what I’m trying to teach.”

Blakesley has been teaching social studies at Palmer High School for more than 11 years. After noticing the increasing presence and impact of misinformation in the media around the 2018 midterm elections, he decided it was time for his class to talk about it.

Blakely’s instinct was correct. A Brookings survey found that 57% of respondents reported seeing some form of fake news during the 2018 election season.

A study published in Sage Journals underlined that such perceptions of mis- and disinformation directly impacted levels of political cynicism as well, further fueling a growing distrust in government and the media.

“We need to be aware of the fact that not everything you see or read or come across on the Internet is trustworthy,” said Blakesley. “I think this learning is understanding how to be good digital citizens, for teachers and students.”

Blakesley’s classes were learning about the U.S. government at that time and he decided to introduce more data-focused investigations into the campaigns and the media surrounding them.

Students were assigned position research papers and Blakesley instructed them to propose Congressional bills with the sufficient background data to justify their proposals.

In order to most accurately pull data for their papers, Blakesley supplemented the assignment with lessons about identifying legitimate sources of information.

“A lot of times students and adults say, ‘Well, I want to find a source that doesn’t have any bias,’” said Blakesley. “I try to point out that, well, every source has bias. I like to think of it more as a point of view.”

Blakesley has tapped a number of publicly available media literacy resources including those provided by Stanford's Stanford History Education Group, which is now an independent nonprofit known as the Digital Inquiry Group (DIG).

The DIG offers history curriculum and digital literacy materials aimed at teaching students and educators how to be more critical and mindful consumers of information.

Additionally, Blakesley began pulling examples of misinformation from his own life. He and his students analyzed Twitter screenshots touting questionable research findings and news articles citing doubtful sources.

They employed media literacy practices such as lateral reading to dissect the examples.

Lateral reading is the process of opening multiple tabs on specific subjects and reading laterally (across) the numerous tabs as opposed to simply reading up and down the single source.

“Look up the author’s name,” said Blakesley. “You can look up the website, the organization… find out information behind the source that you’ve just found on the Internet.”

The class has looked deeper into various conspiracy theories as well, including claims that the moon landing was faked.

And while the moon example may seem silly, a 2021 study out of the Casey School of Public Policy at the University of New Hampshire found that 12% of respondents believed the 1969 landing was not real.

That’s up from the 6% reported in a 1999 Gallup poll.

Blakesley and his classes inspected both liberal and conservative-leaning social media pages and websites, scrutinizing where perspective and bias might be leaking into what otherwise appeared as factual reporting.

Blakesley found that, while students seem to engage in and understand the media literacy techniques within the classroom, one of the biggest inhibitors to continued practice is what he calls “apathy” towards the media.

And it’s not just teenagers who express such apathy.

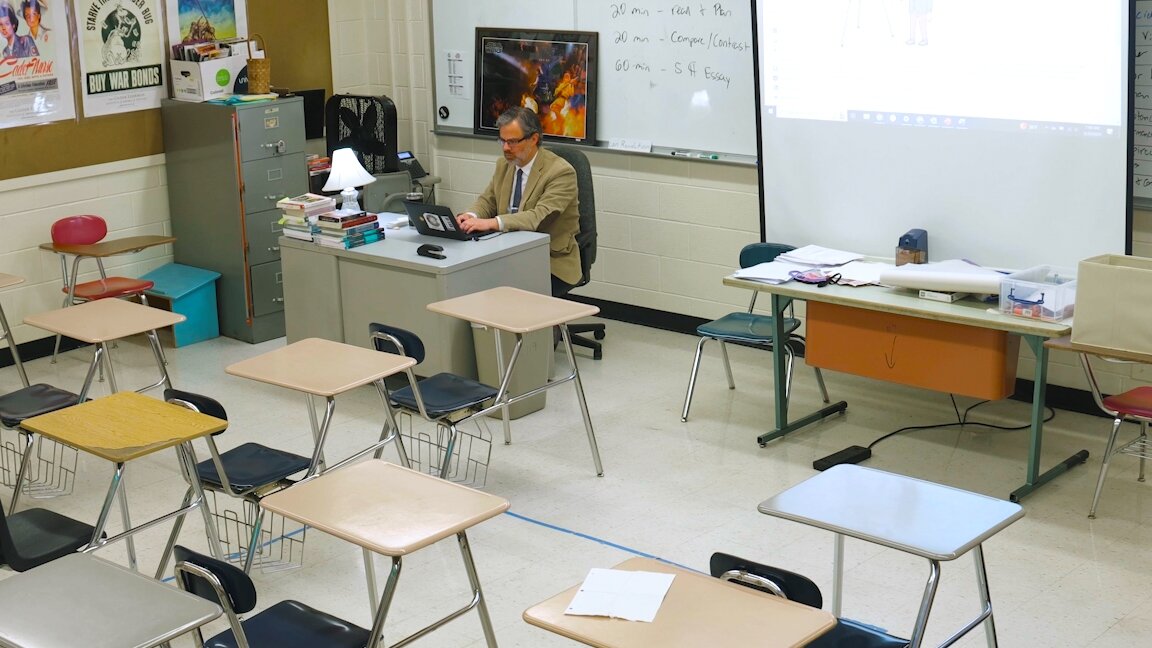

An “apathy” towards media literacy practices can make teaching such techniques difficult.

Photo: Chase McCleary, Rocky Mountain PBS

“Teens and adults both struggle with this,” said Blakesley. “They ask, ‘Why take the time to look up information?’”

State legislators in Colorado have taken notice of media literacy as well.

The Colorado House Bill “Concerning Implementing Media Literacy in Elementary and Secondary Education,” passed in 2021, a significant step towards highlighting media literacy in the state.

The bill created a specific advisory committee within the Colorado Department of Education dedicated to determining best practices for implementing medial literacy in many Colorado schools.

And while this resulted in the creation of resources including the state’s Media Literacy Resource Bank, the bill does not require “schools or school districts to adopt or implement the materials or information into current curriculum.”

Blakesley knows that not every student will follow adequate media literacy practices everytime they are online or on social media.

However, he hopes that by raising awareness of the mis- and disinformation present in the modern day media landscape, he can help make day-to-day scrolling a bit more “purposeful.”

“The more informed we’ll be, the better citizens not only online, but in person we’ll be,” he said.

“And I think that goes a long way to maybe not necessarily solving our political problems and discourse, but it’ll definitely help our political discourse.”

Blakesley sported a Constitution-themed tie, a gift from his students while on a Washington D.C. field trip.

Photo: Chase McCleary, Rocky Mountain PBS

Chase McCleary is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. Chasemccleary@rmpbs.org.

Rocky Mountain PBS is committed to improving digital media literacy in Colorado.

In order to advance the practice of fact-checking and creating a better informed, more engaged public, the Rocky Mountain PBS Journalism team has launched Reality Check, a nonpartisan educational initiative dedicated to creating a more media literate Colorado.

To learn more, you can visit us online or follow us on Instagram and TikTok at @rmpbs