An Aurora classroom's final assignment was writing letters to Club Q victims

AURORA, Colo. — After hearing the news that five died and 18 were injured in a shooting at Club Q, an LGBTQ+ bar in Colorado Springs, Tim Hernández’s first concern was his students at Aurora West College Preparatory School, where he teaches ethnic studies.

“We have LGBTQ students in every class, in every school, in every district, in every state,” Hernández said. “Understanding and reeling with that was very emotional for me, but I also was cognizant that I couldn’t imagine what it must be like to be a queer person and wake up to the news of that shooting.”

Hernández’s class studies freedom movements such as the fight for Palestinian liberation, the work of the Black Panther Party and the Stonewall Riots, the last of which are often pointed to as the foundation for the modern-day LGBTQ+ rights movement.

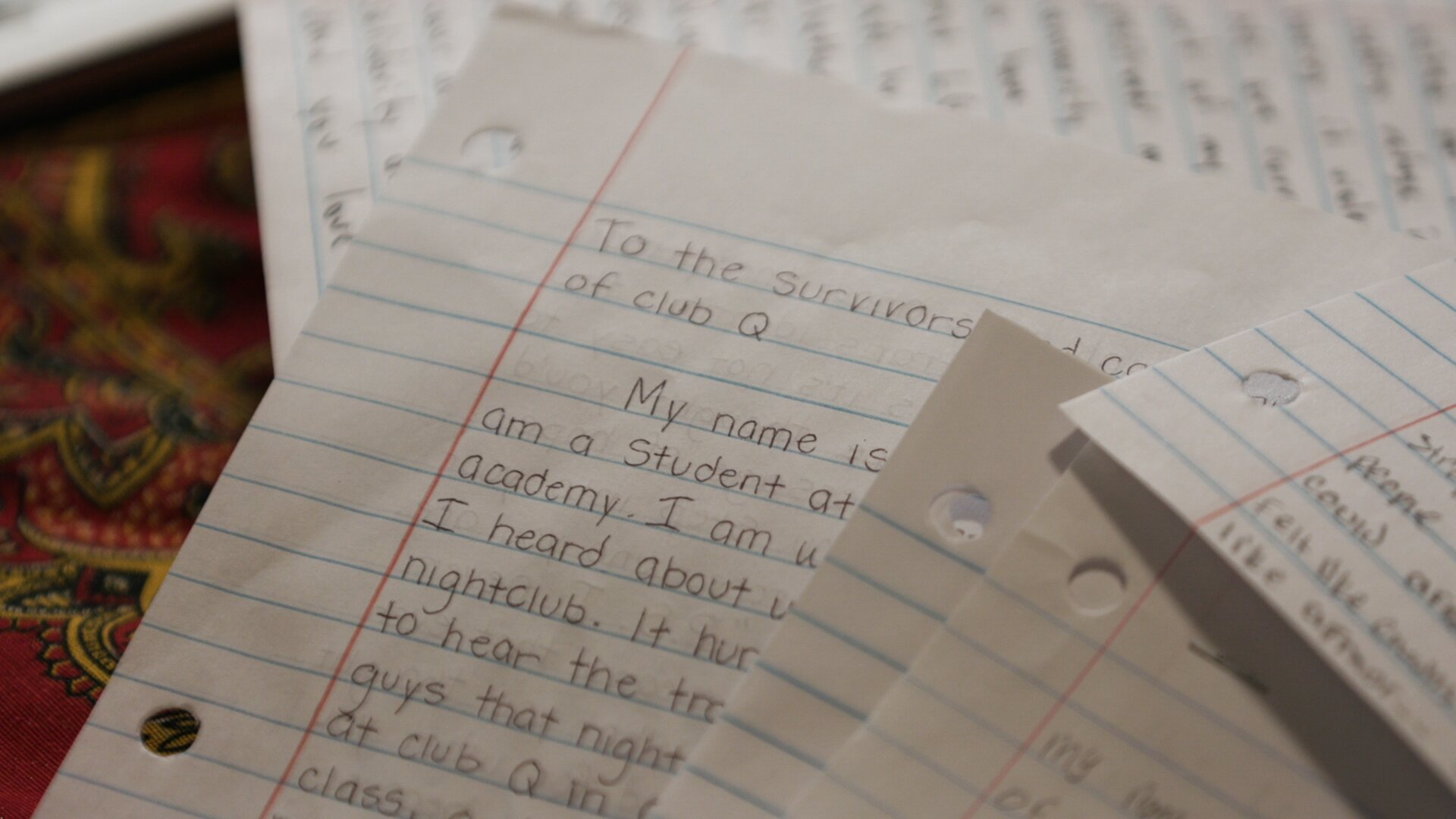

The week of the Club Q shooting, Hernández's class was studying queer history, as well as ways to support marginalized groups. After discussing their shared rage and sadness over the shooting, students suggested writing letters directly to victims and families of those who died.

“We have to take a very clear stance about what kind of society we want to be a part of,” Hernández said. “I deeply want to be part of a society where that’s not something that happens again.”

Hernández knows his class could have written letters to legislators asking for stricter gun laws, but he explained that healing is just as important as fighting, which is why he specifically assigned letters in solidarity with victims.

“Unless we give students an active role in creating what they want a just society to be, then we have no real opportunity to build one,” Hernández said.

Before accepting the job in Aurora, Hernández taught at North High School, just two blocks from where he grew up. As a longtime resident of Denver’s heavily Latino northside, Hernández felt he had a unique ability to relate to students in his classroom at the school. During his one-year tenure at Denver North, Hernández taught about the same liberation movements he currently teaches in Aurora.

After his first semester, Hernández was told the school would not be renewing his contract. School administrator’s pointed to poor interview performance as justification for their decision, but Hernández believes the real reasons boiled down to racism and disagreement with what he was teaching.

“I’m working within an education system that is not interested in sustaining teachers like me,” Hernández said. “Education is political. Teaching is political.”

In Aurora, Hernández’s teaching philosophy remains the same: students deserve information and access to create a better world than the one they were born into.

“All I care about is educating students, young people who are going to be voters, young people who are going to be workers, young people who are going to be teachers,” Hernández said. “I want them to know that there are ways of existing in this world beyond what we’ve been taught.”

Alison Berg is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at alisonberg@rmpbs.org.

Jeremy Moore is a senior multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach him at jeremymoore@rmpbs.org.

Related Stories

“Legislation is only going to get us so far,” Hernández said. “My kids believe that everybody deserves to feel safe, whether it’s a classroom or a nightclub, and my kids know that they’re responsible for creating those safe spaces for themselves in the future.”

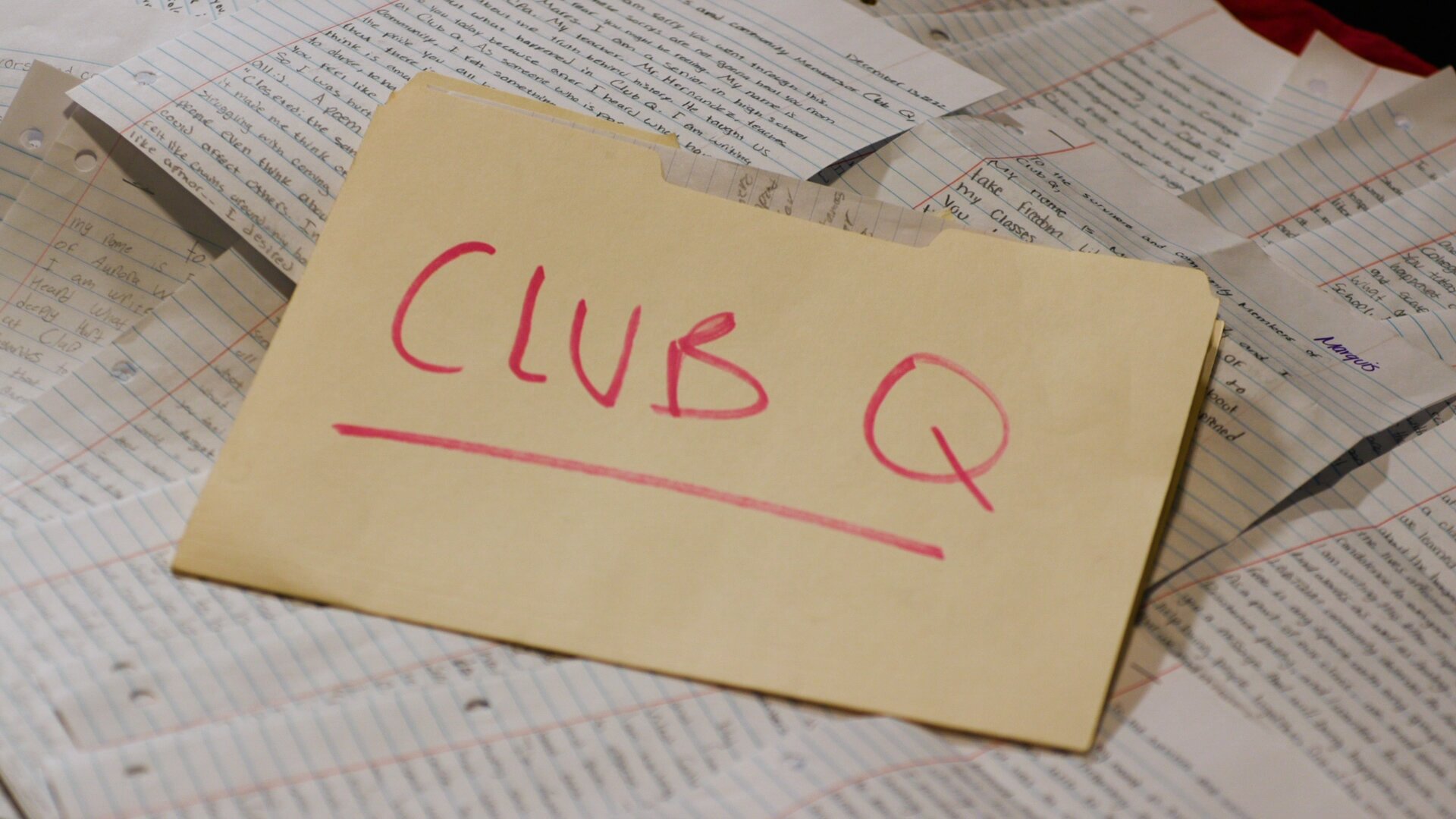

The letters were the students’ final assignment, and letters included personal anecdotes from LGBTQ students, poems about love and support, as well as general messages of hope and healing.

“These are real people who experienced a real loss and a very real traumatic event that's going to change the rest of their lives,” Hernández said. “Hopefully this is just one small part of letting them know that we exist here with them.”

While his students discussed the history of LGBTQ+ liberation, many pointed to current vitriol for those in the LGBTQ+ community, like legislation passed around the country banning medical care for transgender minors and politicians proposing to outlaw drag shows.

Though the future may feel bleak to many, Hernández believes an optimistic path forward rests in the hands of younger generations, including the students who sit in his classroom each day.