A woman's place is in the auto shop as nationwide shortage draws new recruits

DENVER — Jordan Delitz is the only female technician at the auto shop where she works. In fact, she’s the first female technician to ever work there.

This has been the case at almost every auto shop she’s worked at throughout her six-year career.

“I've had a lot of challenges being talked down to, being gaslighted,” Delitz said. “It's like these men are talking to me like I'm their wife and not their coworker and not treating me with the equal respect that I deserve.”

Delitz works at Jeno’s Auto Service in Littleton. [Note: Jeno’s Auto Service is owned by the father of Rocky Mountain PBS managing producer, Amanda Horvath. She did not contribute to this report.]

She has worked in the automotive service industry for six years, but this is the first time she’s found a shop where she wants to stay long term.

“It's taken probably about seven or eight different shops to find this one where I feel like I actually fit in, and [my boss] respects me,” Delitz said. “He treats me like a person and not a woman.”

Last year, women accounted for just 2.5% of automotive service technicians and mechanics in the U.S., according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As shop owners, dealerships and drivers feel the effects of a nationwide shortage of automotive technicians, creating more opportunities for women in the industry could be part of the solution.

“I think a huge aspect of our shortage could be helped if we were better at attracting female technicians,” said Phil Carpenter, director of operations at Urban Autocare in Denver. “If we're missing half of the population to start off with, that doesn't help in trying to fill the need.”

Out of the 20 technicians Carpenter employs, none of them are women. Carpenter said he’d be thrilled to interview a female technician, but he can’t remember the last time he received a job application from one.

A cycle of missing representation

Laura Lewark is the co-owner and office manager of Ski Country Auto Repair and Towing in Frisco. She is one of three women on her staff of 24. The two women she works with are towing dispatchers, so they work in administrative positions.

Lewark said she wants to hire a female technician and a female tow truck operator, but applications from women for those positions are rare.

Lewark suspects that she sees so few applications from female candidates because there are so few women working in those roles already. She said when girls and women don’t see themselves working as technicians or tow truck operators, they don’t consider it a career option.

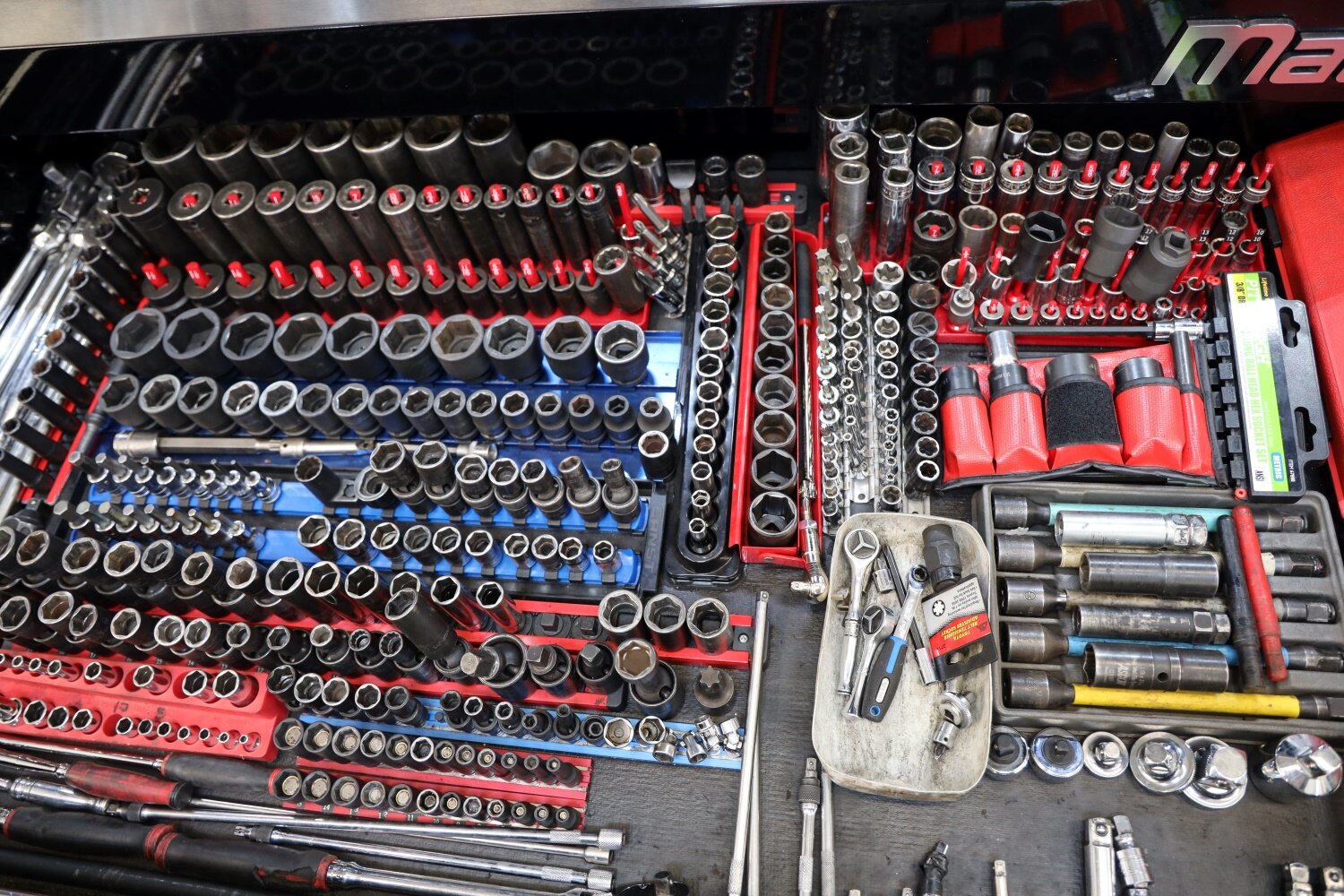

“I think it's probably [due to a] lack of knowledge, and maybe lack of support, that this is something that they could do,” Lewark said. “Just because you're male doesn't mean you're the only one that could work on a car. It's nuts and bolts. If you have that technical mindset, any gender could work on a vehicle. Any gender can be trained to tow a vehicle."

“It's nuts and bolts.” Shop owner Laura Lewark said anyone with a technical mindset could be trained to work on a car, regardless of gender.

Photo: Carly Rose, Rocky Mountain PBS

Addyson Gregory, a 16-year-old junior at Mountain Range High School in Westminster, participates in her district’s career and technical education program called Future Forward.

Gregory spends half her school day taking core curriculum classes, such as math and English. Then she heads to the Future Forward campus to learn the trade she chose to study: diesel technology.

The program offers other areas of study, including automotive technology and auto body collision and repair. Gregory initially chose diesel technology because she planned to become a horse trainer, and she wanted to know how to fix the trucks she’d be using to haul the horses.

After a budget planning workshop in her economics class, Gregory said she realized she could make a better living as a diesel technician than she could as a horse trainer. Now, her goal is to begin working as a technician after graduation and one day manage her own shop.

Gregory said she’s never been one for sitting still, and she loves being able to work with her hands and feel pride in the accomplishment of fixing something on her own.

There are three girls among the 25 students in Gregory’s diesel technology class. She said this ratio is about the same across the other automotive-related classes in the program. Gregory seconded Lewark’s theory about why the demographics in her class — and the industry — are so skewed.

“I feel like [women] are just scared to step out of social norms to do a career that they could potentially fall in love with because they don't see anybody else in it growing up,” Gregory said.

Gregory said she noticed the absence of women from auto shops growing up, but it didn’t deter her from considering the career. She credits her dad with encouraging her to not let gender expectations keep her from doing what interested her.

Within her own family, Gregory saw examples of women working on vehicles. Both of Gregory’s older sisters took automotive technology classes through the Future Forward program, though they don’t work in the automotive industry now.

Discouraged by a culture of bias

Although Gregory’s diesel technology class is predominately male, it’s taught by a female technician. In addition to teaching them the skills of the trade, Gregory said her instructor gives her and the other female students in the class tips on how to handle the shop environment as a woman.

“She understands all the negative comments going into a shop,” Gregory said. “We have a conversation almost every week about how she experienced something in the shop because she was a female. She's just trying to teach us how to be tough, in a way.”

While Gregory is still steadfast in her goal to become a technician, some of the stories from the shop that her instructor shares do worry her, like the times when she describes taking the brunt of the blame for mistakes at the shop.

“She had to deal with customers and mechanics who were frustrated at the time about the situation and just took it all out on her,” Gregory said. “It's kind of scary because I could just be doing my own thing, and the other people could just release their anger on me.”

Delitz has her own stories about the biased treatment she’s experienced as a female technician. She said she’s had work taken away from her and reassigned to other technicians without her knowledge.

Male coworkers at previous shops would often ask to double-check her work and a previous employer told her she didn’t have the skill set to work full-time hours. She’s worked at several shops that didn’t have a women’s bathroom at all.

Delitz said she’s had to work twice as hard to prove herself as a technician. While she loves what she does, she can see how the workplace challenges she’s faced could deter women from pursuing a career in the automotive industry.

“It is very discouraging at times,” Delitz said. “I think there's a lot of people that aren't willing to sit in the uncomfort or don't want to step into the unfamiliarity at all.”

Even as co-owner of her shop, Lewark still finds herself needing to prove to some customers that she knows what she’s talking about. Sometimes she answers the phone to help a customer, and they ask to speak to someone else.

“They're very insistent on talking to the man in charge,” Lewark said. “I'll have to say, ‘I am the owner. I am in charge.’”

Changing the narrative

Getting more women involved in the automotive industry begins with letting more girls know that it’s an option for them. Lewark said that should begin in the schools.

She said middle and high schools should be as supportive of students pursuing trade careers as they are of students going to college, across all genders.

“The more that it's out there and the more that it's discussed, hopefully that will change that mindset and open those doors and those thoughts to young women,” Lewark said.

Gregory — whose school’s trade education program fostered her interest in becoming a technician — agrees that schools could help expose students to more career options, especially those they may not have considered.

“I feel like if there would be more field trips to locations that have more women in a field that's male-dominated, it will help with the younger generation,” Gregory said.

Delitz is used to her male coworkers underestimating her as a technician.

Photo: Carly Rose, Rocky Mountain PBS

Delitz suggests that shop owners focus on fostering skills in new technicians — of all genders — rather than prioritizing perfection on the first try.

At previous shops and dealerships where she’s worked, Delitz said she wasn’t given the opportunity to learn from her mistakes after tackling a new skill. Once she made an error, she wasn’t given the chance to try it again, she said. This could be discouraging for technicians who are just entering the industry, especially women who already feel a pressure to prove themselves.

“I think that there needs to be more opportunities for apprentice programs,” Delitz said. “Just being able to get these women in here and let other people see what the hell they can do before you just judge a book by its cover.”

One stereotype of car maintenance is that physical size is a prerequisite for being a successful mechanic. Phil Carpenter said that when he got his first job as a technician 20 years ago, he worried that his smaller stature would be a weakness. However, he found his small hands and wrists to be an advantage when working on the fine details of a vehicle.

“I have the smallest hands in the game,” Delitz said. That means she can take off fewer parts of a vehicle before she’s able to fit in the space she needs to address the mechanical issue.

While strength and height are beneficial in other aspects of the job, Delitz doesn’t think it’s any reason to disqualify someone from this kind of work.

“It's discouraging to have somebody think that I can't lift tires or something else just because I'm as short as I am or as small as I am,” Delitz said. “It doesn't matter. I’ve found a way to make it work.”

The culture of the automotive industry has already begun to change as more women enter its ranks, Lewark said.

National organizations like Women in Automotive connect women working in the industry, creating opportunities for networking and mentorship, even for technicians who are the only woman at their shop. Women in Automotive will host its annual conference in Colorado Springs next month.

Delitz’s advice for budding female technicians is to get comfortable with being uncomfortable — and the same goes for male technicians wary of women joining their shops.

“At the end of the day, there's going to be more of us coming,” Delitz said. “I'm not going to be the last, so they need to get used to it.”

Carly Rose is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. Carlyrose@rmpbs.org.