Whistleblowers say they falsified patient records at a Western Slope mental health center

If you’re struggling, help is available on Colorado’s crisis hotline. Call 1-844-493-TALK(8255)

GRAND JUNCTION, Colo. — A troubled Western Slope mental health care center falsified assessments of its patients’ conditions for at least nine years in an effort to make its treatment programs seem more effective and secure funding from the state, whistleblowers say.

The state overlooked what former workers describe as a long practice by the Grand Junction-based Mind Springs Health of intentionally writing bogus patient evaluations. The three departments tasked with regulating Colorado’s mental health safety net system failed to notice the allegedly falsified reports during a recent multi-agency audit of the center, and over years of lax oversight.

“You’ve got to wonder how closely these so-called regulatory agencies are really looking,” says Sunny Sullivan, one of 29 current and former Mind Springs workers who have come forward to tell the Colorado News Collaborative (COLab) what they see as legal and ethical breaches.

Among the allegations, Sullivan and five other former workers say their supervisors had them and their colleagues fill out mental health assessments of patients they knew little or nothing about and hadn’t actually evaluated. The whistleblowers, who were not trained in behavioral health care and had no clinical licenses or experience at the time they worked for Mind Springs, say their bosses also told them to:

- Make up diagnoses for patients to justify treating them

- Diagnose certain patients with disorders they did not have in order to qualify them for costly, Medicaid-funded treatment they did not need

- Show progress among all patients they were assigned to assess – including those whose symptoms had not actually improved – because state funding for the center hinged partly on the success of its treatment

Mind Springs’ longtime CEO Sharon Raggio and two of its other top executives resigned following a Colorado News Collaborative investigation about access to and quality of the center’s care. Interim CEO Doug Pattison and the center’s spokeswoman had not returned multiple emails and phone calls over several months about these latest allegations before the deadline for this story.

The former workers’ accounts span from 2012 to 2021, suggesting that falsifying records wasn’t merely a one-off or an occasional mistake in a state where the law is silent about specifically who should complete those records and how. Rather, whistleblowers say this was an intentional practice of concocting patient information that gave state regulators and policymakers a distorted view of Mind Springs’ effectiveness and, most likely, resulted in the center reaping more public funding than it would have otherwise.

“I’m no legal expert, but I’m pretty sure what we were doing was fraud,” says former case manager Amy Jensen, who estimates she took part in doctoring at least 1,000 patient assessments between 2014 and 2018.

“I’ve wondered how long it could go on without anyone at the state bothering to do something about it.”

“CCAR parties”

Mind Springs is one of 17 regional community mental health centers statewide that have long made up the core of Colorado’s safety-net system.

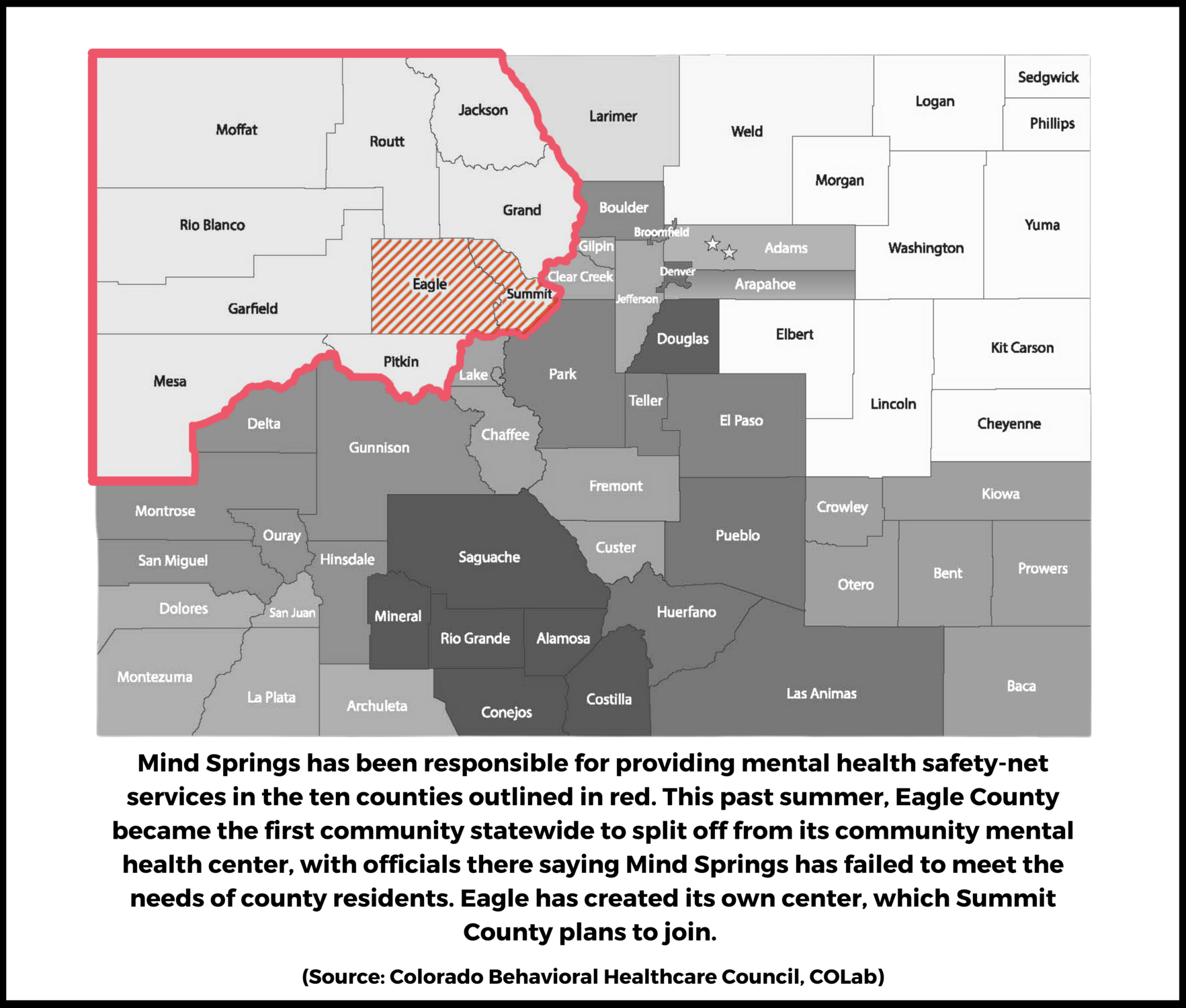

The center serves people in 10 Western Slope counties: Eagle, Garfield, Grand, Jackson, Mesa, Moffat, Pitkin, Rio Blanco, Routt and Summit. Its last financial disclosure, from 2019, shows it received $26 million annually to provide inpatient hospitalization, intensive outpatient treatment, outpatient psychiatric care, counseling, and other forms of treatment for Medicaid recipients and indigent people under its exclusive contracts with the state.

Those contracts – and the contracts of the 16 other community mental health centers – will no longer be exclusive under a massive bill passed last week to reform Colorado’s safety net system. The law creates a new set of policies that will be carried out by a cabinet-level agency called the Behavioral Health Administration, which, upon its launch in July, will replace the state’s current Office of Behavioral Health within the Department of Human Services.

The Behavioral Health Office long has required the centers and other mental health care providers complete evaluations called Colorado Client Assessment Records, or CCARs for short, for each person receiving Medicaid or other publicly funded care. One CCAR must be filled out upon intake for treatment and another when treatment has ended. Care providers must submit additional CCARs for clients in long-term therapy and for psychiatric patients who are medicated or hospitalized long-term.

The 8-page evaluation asks, among other information, for the client’s diagnosis. It also poses 25 subjective questions meant to assess their current mental health status: their levels of depression or hope, their grasp on reality, and their ability to function without treatment, for example. The person filling out the questionnaire is supposed to interpret often complex and contradictory answers, synthesize them with what they know about the client’s current mental health status, and rank each on a severity scale from 1 through 9 – 1 meaning wellness and 9 indicating crisis.

Clients typically don’t see their CCARs. They’re mainly administrative records to help guide the state in paying providers for services through Medicaid and tax-funded grants.

From a policy perspective, the evaluations help state agencies track who’s getting state and federally funded mental health treatment and the extent to which it’s helping. The state also uses aggregated data from the reports to inform lawmakers about the efficacy of Colorado’s overall mental health safety-net system. The clarity of that picture depends on the accuracy – and truth – of the information providers like Mind Springs submit.

From a clinical standpoint, the mere mention of a CCAR form can trigger groans among psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses and other care practitioners who often complain the assessment and other mandatory state paperwork take too long to complete. Because the need for publicly funded mental health care services far exceeds the number of clinicians available, the people most familiar with patients’ cases and who are most qualified to assess them often are slow to fill out the reports. That leaves backlogs of CCARs that need to be completed and submitted to the state in order for a provider to get paid.

At Mind Springs, management passed at least some of its CCAR backlog to employees in its hospital admissions office and to other workers who lack the behavioral health care training and experience most experts say is needed to diagnose people with mental health challenges and assess their well-being. They also lacked access to direct communication with patients, which state policy requires of people doing CCARs.

By the time they were assigned to fill out a CCAR, whistleblowers say the patient usually was long gone from treatment or discharged from Mind Springs’ psychiatric hospital. And so they typically filled in clients’ diagnoses blindly, often guessing that they had conditions such as general anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, or schizoaffective disorder. Sullivan – then a team leader in the hospital admissions office – says her supervisor told her and her staff to write in “adjustment disorder” under the reasoning “that everyone has trouble adjusting to something, so nobody would be questioning that diagnosis.”

Mind Springs’ objective, as whistleblowers tell it, was speed, not accuracy.

“They said just put down your best guess, and fast,” says Sarah Mackie, who also worked in hospital admissions. “I had no sense of who these patients were. I had no clue how they would (have) answered these questions about themselves. And I had no idea what I was doing.”

“I had zero business – zero, zero, zero – diagnosing people,” adds Jennifer Hector, another former employee of the admissions office.

Each of the whistleblowers says she was encouraged to work on CCARs whenever she had downtime on a shift. Some were called in to work evenings or weekends to complete hundreds of the assessments in Mind Springs’ backlog. Supervisors referred to those occasions as “CCAR parties,” says Hector, who estimates she completed about 700 of the questionnaires in one year alone, 2015. “You just sat there, put your head down and did nothing but fill out those forms.”

The single mother of seven says she told her supervisors “I don’t want to do this” and “I’m not comfortable… messing with the state of Colorado and funding.”

To her many objections, she says they had the same response:

“That I didn’t have a choice.”

Jensen, the former Mind Springs case manager, also struggled with signing her name to phony assessments of people she wasn’t even sure were still alive. She says supervisors assured her the assignment was legal and urged her to stop raising objections.

“They had us flat-out making stuff up, then came down on us for asking if it was legal or even ethical,” she says. “I felt like I was in the Twilight Zone. Like, am I nuts? Why does everybody think this is OK?”

Asked why she did not come forward about the falsified reports sooner, Jensen says she had no confidence in state regulators to do anything about it and says she feared that publicly acknowledging her own role in defrauding the state could damage her new career and license as a professional counselor.

Financial incentives

Four of the five whistleblowers say supervisors instructed them, when working on a client’s discharge evaluation, to answer all 25 questions about mental health symptoms at least one number lower in severity than the corresponding number on that client’s intake CCAR. Mind Springs’ goal, they say, was to document that clients had improved from its treatment, whether or not that was actually true.

“We’d ask can we go read their treatment plans or their charts, and they’d say no, just mark them better, just mark them a point or two lower on all the questions,” Hector says.

Mind Springs’ preoccupation with showing improvement sometimes caused tensions between employees and departments. Sullivan recalls terse emails from an inpatient nurse asking why a CCAR evaluation blindly filled out by a staffer Sullivan supervised did not mention the patient’s extreme psychosis.

“She was frustrated. She had a hard time showing he had improved because what was written didn’t reflect his real symptoms,” Sullivan says.

Mental health care records are protected under HIPAA, leading the state to refuse the Colorado News Collaborative’s requests for CCARs submitted by Mind Springs and for certain data gleaned from them. Without what likely would be a prolonged – and expensive – legal battle, there is little chance someone outside the system could ascertain how many of Mind Springs’ clients have been misdiagnosed, mistreated or treated unnecessarily because the center falsified their assessments.

“What this means to people who needed help really bothers me. I hate to think of how many people weren’t getting the right treatment because of that,” says Reggie Bicha, who ran the Human Services Department under former Gov. John Hickenlooper.

It was under Bicha’s leadership that the state started to hinge its exclusive contracts with community mental health centers partly on their performance. Bicha’s behavioral health staff worked with each center to set quality improvement goals it had to meet in order to receive its monthly reimbursements from the state and renew its annual contract.

In fiscal year 2016-2017, for example, “improvement of symptom severity” was one of Mind Springs main performance goals. The state was only able to monitor progress through CCAR data.

In fiscal year 2017-2018, Mind Springs stood to lose up to $257,000 in state funding if it failed to show that symptoms of its adult clients’ depression were becoming less severe in the first six months of treatment and that the severity of those symptoms eased by 50% within a year. CCARs were key in demonstrating – or at least purporting to demonstrate – progress.

Mind Springs’ contract in fiscal year 2019-2020 shows the Office of Behavioral Health had concerns about the accuracy of information the center was submitting to the state. The contract listed “successful data submission” – including more complete and accurate CCARs – as one of the key performance goals it had to meet that year. If Mind Springs didn’t hit that target, the state warned that its unearned performance payment dollars could have been distributed to other community mental health centers that were meeting their goals.

That threat didn’t materialize, says a state official who asked not to be named because her agency forbids employees from speaking to the news media. She noted the irony that regulators may have carried through with the threat had anybody in the Behavioral Health Office thought to look for falsifications and not just for omissions on Mind Springs’ CCARs.

The often cash-strapped center had other possible reasons to falsify client assessments, including a program that gave centers the opportunity to earn extra funding if they “exemplify(ied) extraordinary performance.” That statewide pot was small at first, at only $50,000 in fiscal year 2016-2017, but by fiscal year 2017-2018 had grown to $3.9 million.

As Bicha tells it, a program that had real potential of boosting Mind Springs’ cashflow may have backfired.

“The intention of our performance management was to understand problems, hold ourselves and our partners more accountable and to drive better results for the people of Colorado,” he says. “A system that has contractors gaming it flies in the face of all of those priorities.”

Whistleblowers point to other incentives at play.

Jensen, for example, recalls being assigned to evaluate clients serving parole with a community corrections company that partnered with Mind Springs. She says two of her supervisors and one member of upper management instructed her to diagnose every one of those parolees with a substance abuse disorder, regardless of whether they had a history of substance abuse. The diagnosis ensured that each parolee would qualify for a costly, Medicaid-funded intensive outpatient program that brought in money for Mind Springs.

As a private nonprofit, Mind Springs is not required to disclose how much it made from its partnership with the company.

Oversight overlooked

The Colorado News Collaborative’s investigation into Colorado’s mental health safety net focused not just on troubles at Mind Springs, but also more broadly on state agencies’ longtime failure to regulate community mental health centers.

Shortly after those stories appeared in at least 30 partner news outlets statewide, Gov. Jared Polis’s administration announced the state was conducting a surprise audit of Mind Springs, and touted that three state departments would be involved.

The Colorado Department of Public Health & Environment found “zero deficiencies,” its records show.

The Department of Human Services found Mind Springs failed to report 40% of “critical incidents” such as botched prescriptions, violence, injuries, patient escapes and staff wrongdoing within the required 24 hours, and to provide patients being released from its hospital with the proper paperwork for continued treatment. It also found a few data submission errors, but falsified client evaluation was not among them.

The Department of Health Care Policy and Financing – which controls the Medicaid funding that makes up most of community mental health centers’ budgets – announced Thursday that it found Mind Springs has been using various auditing methods and statistics that have allowed it to expand its government revenues without expanding its services. It also found a need for Mind Springs to simplify its complex corporate structure and to improve the quality of its care.

As part of the audit, nobody from the three state departments reached out to any of the 29 current and former Mind Springs workers who at that time started contacting the Colorado News Collaborative about a long list of legally and ethically questionable practices at the center. Those include:

- Mind Springs executives discouraging its staff from reporting “critical incidents”

- Several accounts of West Springs Hospital inappropriately housing teenage patients alongside adult patients with histories of sex offenses

- Allegations of on-site sexual activity and violence among and between Mind Springs staff members and clients

- And a pattern, which almost all the whistleblowers described, of Mind Springs prioritizing care for privately insured clients over the Medicaid recipients and indigent people the state and federal governments pay it to serve

The whistleblowers hold little faith in state audits.

“Mind Springs Health was audited all the time. We saw auditors in and out of that place and they never seemed to see what we were seeing, or even ask us. It makes me wonder if they even took their jobs seriously or if they simply ignored possible issues of fraud,” Sullivan says.

For months this winter and spring, the Human Services Department downplayed the relevance of allegations about falsified CCARs, saying state law gives leeway in how mental health providers fill out state reports. A spokeswoman, who since has left the department, emailed in March that state policy “does not dictate the physical location in which CCARs must be filled out and in most cases does not specify who can fill out a CCAR.”

“OBH Rule does not require an assessment to be performed in person… or by a licensed individual,” Maria Livingston wrote an apparent attempt to justify Mind Springs’ approach to the evaluations. “OBH staff routinely review CCAR data in line with the CCAR Data Reporting Policy as part of regular licensed/designated-provider site visits and reviews. The review involves checking to see if CCAR data is incomplete or missing.”

She would not say whether the reviews also look for accuracy.

Medicaid officials at Colorado’s Department of Health Care Policy and Financing also had little interest in whistleblowers’ accounts of falsifying CCARs at Mind Springs when the Colorado News Collaborative asked about them in the winter. Although they rely on data from CCARs, they said, the assessments are the Behavioral Health Office’s responsibility.

But earlier this spring, Rocky Mountain Health Plans, the company the Department of Health Care Policy and Financing pays to manage Mind Springs’ Medicaid contract, responded to the Colorado News Collaborative’s account of whistleblowers’ allegations by launching an investigation into possible waste, fraud and abuse. The company’s contract with the department obligates it to investigate and report about those types of allegations.

It was only then that the Department of Health Care Policy and Financing triggered its own internal review and said it is taking the allegations “very seriously.”

Last week, the Human Services Department stopped downplaying whistleblowers’ accounts and said it, too, is now launching its own new investigation into the accuracy of Mind Springs’ CCARs, among other things.

Whistleblowers, though buoyed by news of the state’s sudden interest, are skeptical.

“I worry this is a disingenuous PR move,” says Jensen.

Adds Sullivan: “I hope this time they actually take their investigations seriously.”

This investigation is part of the ongoing "On Edge" series about Colorado’s mental health by the Colorado News Collaborative, the nonprofit that unites more than 160 communities and news outlets like ours to ensure quality news for all Coloradans. The series title reflects a state that has the nation’s highest rate of adult mental illness and lowest access to care, and the fact that state government is on the edge of either turning around its behavioral health care system or simply reorganizing a bureaucracy that is failing too many Coloradans.