State Wage Theft Cases Number in Thousands Each Year, Inquiry Finds

Wage theft – a term for employers illegally withholding wages – is rampant across Colorado.

From telemarketers to tortilla manufacturers, workers in myriad industries have suffered from employers failing to pay them wages they are owed, a Rocky Mountain PBS I-News investigation has found.

While blue-collar workers are most frequently cheated, workers across pay-scales in Colorado are vulnerable to wage theft, the analysis of federal enforcement data shows.

Since 2005, the federal Department of Labor has recovered over $31 million in wages that had been illegally withheld by employers in Colorado in violation of the Fair Labor Standards Act.

Across the U.S. the amount of illegally withheld wages was more than $1.4 billion for the same period.

Under the Colorado Wage Claim Act, employers who cheat workers out of wages can face a misdemeanor charge, $300 fine and 30 days in a county jail – penalties the General Assembly put in place in 1941 that have not changed since.

But that law is not being used to hold potentially criminal employers accountable. No charges have been filed under the law since 2001, according to state court data analyzed by I-News.

The investigation shows the patchwork of enforcement options in the state means persistently egregious employers can escape harsh punishment.

Construction Tops in Unpaid Wages

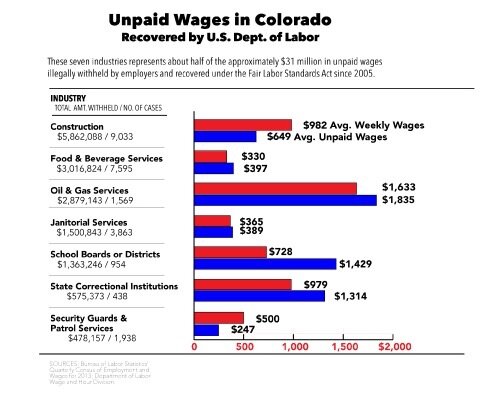

Construction was the largest source of unpaid wages in Colorado, according to the I-News analysis, followed by workers in food service, oil and gas and janitorial services. Wage investigations involving workers employed by local school boards and state correctional institutions were also near the top of the list of wages recovered by federal labor authorities.

The amount of illegally withheld wages can easily equal a week’s worth of pay, according to the I-News analysis. For example, since 2005 the Department of Labor recovered an average of $389 in back wages for each of 3,863 janitors in Colorado, while their average weekly wage was $365, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics’ 2013 data.

The amount in back wages only captures cases that have received scrutiny from Department of Labor investigators – countless other businesses and individual cases escape attention.

Some estimates put the rate of illegally withheld wages much higher. The Colorado Fiscal Institute, a policy think-tank, estimated that workers are deprived of $749.5 million per year, based on applying the rate of wage theft cases found in a 2009 survey of workers in Los Angeles, Chicago and New York to Colorado industries. Those worker surveys found that one-in-four were paid less than minimum wage.

Workers have a few options to force their employers to pay back unpaid wages. They can file a complaint with the state Department of Labor and Employment, and a compliance officer will send their employer a letter to begin an investigation.

The department receives an average of 5,000 complaints a year and recovers about $1 million in unpaid wages, according to agency spokesman Bill Thoennes.

This month, the department received increased enforcement power to issue fines and penalties to employers for noncompliance, and will increase the number of employees involved in investigations from four to nine. Previously, the agency could only refer the parties to mediation.

The federal Department of Labor’s investigations under the Fair Labor Standards Act cover employers with gross revenue of $500,000 or more, or employers that are hospitals, preschools, universities or public agencies.

At the federal level, 96 Colorado cases were filed in 2014 under the Fair Labor Standards Act, the federal law regulating wage and hour conditions. The number of cases filed under the act has tripled since 2009.

The courthouse is also a place some workers turn to recover unpaid wages.

In county courts, workers have filed an average of 73 cases for unpaid wages a year since 2009, according to Colorado court data as of November 2014. Cases from last fall show the diversity of businesses where workers alleged wage theft: a Vietnamese restaurant, a real estate company and even a bison ranch in Grand County.

But the cost of paying an attorney and court filing fees can easily exceed what the unpaid wages are worth.

“A lot of the time when you have small dollar amount disputes, the person who’s been wronged will say, ‘I’m just going to eat that, I’m going to move on, I need to keep working, I can’t devote time to this,’” University of Denver law professor Raja Raghunath said.

Raghunath runs a legal clinic that helps clients with cases of unpaid wages. Feeling confident that no one will catch them is the main incentive for employers to engage in illegal labor practices, he said.

“In this context, increased criminal enforcement of the wage laws would provide significant deterrent effects.”

State’s Wage Claim Act in Disuse

Colorado prosecutors say the state’s wage law is a difficult tool to use to bring criminal charges. The biggest hurdle is proving that the employer intended to “annoy, harass, oppress, hinder, delay, or defraud” the employee by withholding his or her wages. Another obstacle is proving that the employer is able to pay the wages, which means prosecutors have to subpoena company financial records.

The low penalty of $300 and 30 days in jail is too small to make prosecution worth it, said George Brauchler, district attorney for Arapahoe, Douglas, Elbert and Lincoln counties.

“Careless driving? You can get up to 90 days in jail. This, up to 30. Think about that,” he said. “Speeding 25 miles over the speed limit has bigger penalties than this.”

Colorado legislative records show the penalties for wage theft have not been changed since 1941. A bill to strengthen the criminal penalties never made it through the state legislature in 2013.

“My best guess is that it has very little deterrent effect for employers who are willing to engage in this conduct,” Brauchler said.

The state law on theft can also be applied to extreme cases, Brauchler said, but it also requires proving that the employer intentionally did not pay the wages. A defense in which the employer states that he intended to pay the worker later can make theft a high bar to prove beyond a reasonable doubt.

A Denver-based legal services organization, Towards Justice, has advocated in favor of increased criminal charges for unscrupulous employers and cites the effect of unpaid wages on economic growth by reducing consumer spending and tax revenue.

“Allowing wage theft to remain unchecked affects us all,” executive director Nina DiSalvo said. “Work is the foundation of success in America, and if we all believe in that, then we must all fight back against wage theft.”

Boulder Municipal Court vs. Wage Theft

The Boulder Office of Human Rights is active against wage theft complaints, which it takes to Boulder Municipal Court as misdemeanor complaints.

Carlos Vera, who worked for a house painting contractor, said he tried for two months to recover wages he was owed. Instead, the employer asked for Vera’s driver license and Social Security number to intimidate him, Vera thinks. Vera was undocumented at the time. He told the man he still had a right to his wages.

“Good luck, I’ll see you in court,” is what Vera remembers the man saying. Vera filed a complaint with the Office of Human Rights, the employer was charged with “Failure to Pay Wages Due,” and Vera recovered his wages, $400.

Under state and federal law, all workers have a right to wages they earned, regardless of immigration status.

Boulder’s law dates to 2007 and stipulates that employers can be subject to a $1,000 fine or 90 days in jail for failure to pay wages.

Esthetician Monica Harrison did facials and nails at a small salon in Boulder until it went out of business. Harrison and four other workers were owed $7,462 in wages.

Harrison specifically was owed $1,422, making it a big problem for the Boulder resident and single mom.

“I wouldn’t have been able to pay rent or any of my bills,” Harrison said. “I lived paycheck to paycheck.”

After calling their former employer and getting nowhere, the salon workers were able to recover their wages in Boulder Municipal Court without any filing fees.

“If we had to pay money to do it, we probably wouldn’t have done it,” Harrison said.

The difference between the Boulder law and the state law is that the city ordinance is just defined as a failure to pay wages due, and doesn’t require a prosecutor to show that the employer intended to steal the wages from the employee.

Denver also has an ordinance that criminalizes unpaid wages, but unlike Boulder’s law, it is part of the law against petty theft, which covers theft of objects like bicycles, for example. Also, Denver doesn’t support any city office akin to Boulder’s Office of Human Rights where aggrieved workers can go to lodge a complaint and seek redress under the city’s law.

The Denver City Attorney’s office failed to return multiple phone calls and emails for comment.

The threat of jail or a fine is an important deterrent against illegally withholding wages, Boulder city prosecutor Janet Michels said.

“It sends a message to other employers that the city will hold them accountable for these kinds of violations.”