Colorado health officials work to address monkeypox without repeating mistakes of HIV/AIDS crisis

DENVER — As Colorado’s monkeypox case count continues to rise — there have been 134 recorded cases as of Aug. 11 — public health officials are asking themselves what they see as a vital question: how do we get vaccines and information to those who need it most without further stigmatizing an already marginalized community?

The World Health Organization recently declared monkeypox a public health emergency and noted that the virus has primarily infected men who have sex with men. At the same time, WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus warned against stigmatizing the disease.

“Stigma and discrimination can be as dangerous as any virus," Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a news conference.

Alexis Burakoff, the medical epidemiologist with the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE), said public health officials in Colorado are trying to strike the careful balance between making sure men who have sex with men are given first access to the limited supply of monkeypox vaccines and given correct information about the virus without pointing fingers at those men.

“There’s really a balance here between wanting to be transparent with what’s going on with the epidemiology here — what we’re seeing in the data about who is the most at risk right now — and making sure that those messages get out to the communities that need to hear them,” Burakoff said. “Then also making sure that we’re not being stigmatizing or implying that there’s any one community who experiences this differently, because anybody who comes in contact with monkeypox can get it, and that’s important to know as well.”

[Related: As monkeypox strikes gay men, officials debate warnings to limit partners]

The department has worked with LGBTQ+ advocacy organizations like The Center on Colfax and One Colorado to ensure those who are most vulnerable to monkeypox are receiving care and information.

“We’re really engaged in that stakeholder process to make sure that our messaging is sensitive and effective and reaching the people that it needs to reach,” Burakoff said.

Burakoff said the virus spreads primarily among close skin-to-skin contact, and because a man having sex with men was the first to catch the virus in the United States, the infection has spread primarily among that community. Still, Burakoff emphasized that monkeypox is not considered a sexually transmitted infection and that anyone who comes in contact with the virus has the potential to be infected.

“This is not COVID. We want to emphasize that,” Burakoff said. “This isn’t something you’re going to get by walking past somebody in the grocery store. It’s not that level of contagiousness, the highest risk is having direct, skin-to-skin contact with someone.”

CDPHE's website states that vaccine supply is currently "extremely limited" and only those who have come into close contact with someone who has had monkeypox in the last 14 days or gay, bisexual, transgender or nonbinary people who have had multiple or anonymous sexual partners are eligible for the vaccine. As of Aug. 10, roughly 3,100 people have been vaccinated against monkeypox in Colorado.

While public health officials have done their best to avoid repeating the mistakes of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, gay and bisexual advocates who lived through that era say they are seeing parallels between then and now.

“For a population that is very sensitive to those issues and has a history with that, there have definitely been some alarm bells that have gone off for people, especially because it’s spreading so quickly,” said Rex Fuller, the CEO at the Center on Colfax.

Still, Fuller feels the Biden administration has handled the issue with much more care and sensitivity than President Ronald Reagan did with HIV, a disease that the CDC estimates has killed nearly 330,000 gay and bisexual men since the 1980s.

“At the time, there actively was government disregard for the HIV epidemic, specifically because it was affecting gay and bisexual men,” Fuller said. “Things have changed quite a bit.”

Though the vaccine is in limited supply — leaving many who catch the virus to struggle with what they have described as excruciating pain — Fuller said he firmly believes that is because of difficulty in obtaining doses from suppliers overseas, not because of government inaction.

“It wasn’t that people were actively saying ‘who cares,’ it was just a delay in manufacturing,” Fuller said.

Even so, other advocates felt the government’s response may have been quicker if the virus were infecting the general population at the rate it is infecting queer men.

“If the virus were progressing beyond the LGBTQ community and further beyond into the general population, which could be detrimental, many would say the response would be different,” said Gillian Ford, a spokesperson at One Colorado. “Stigma and discrimination are just as dangerous as a virus.”

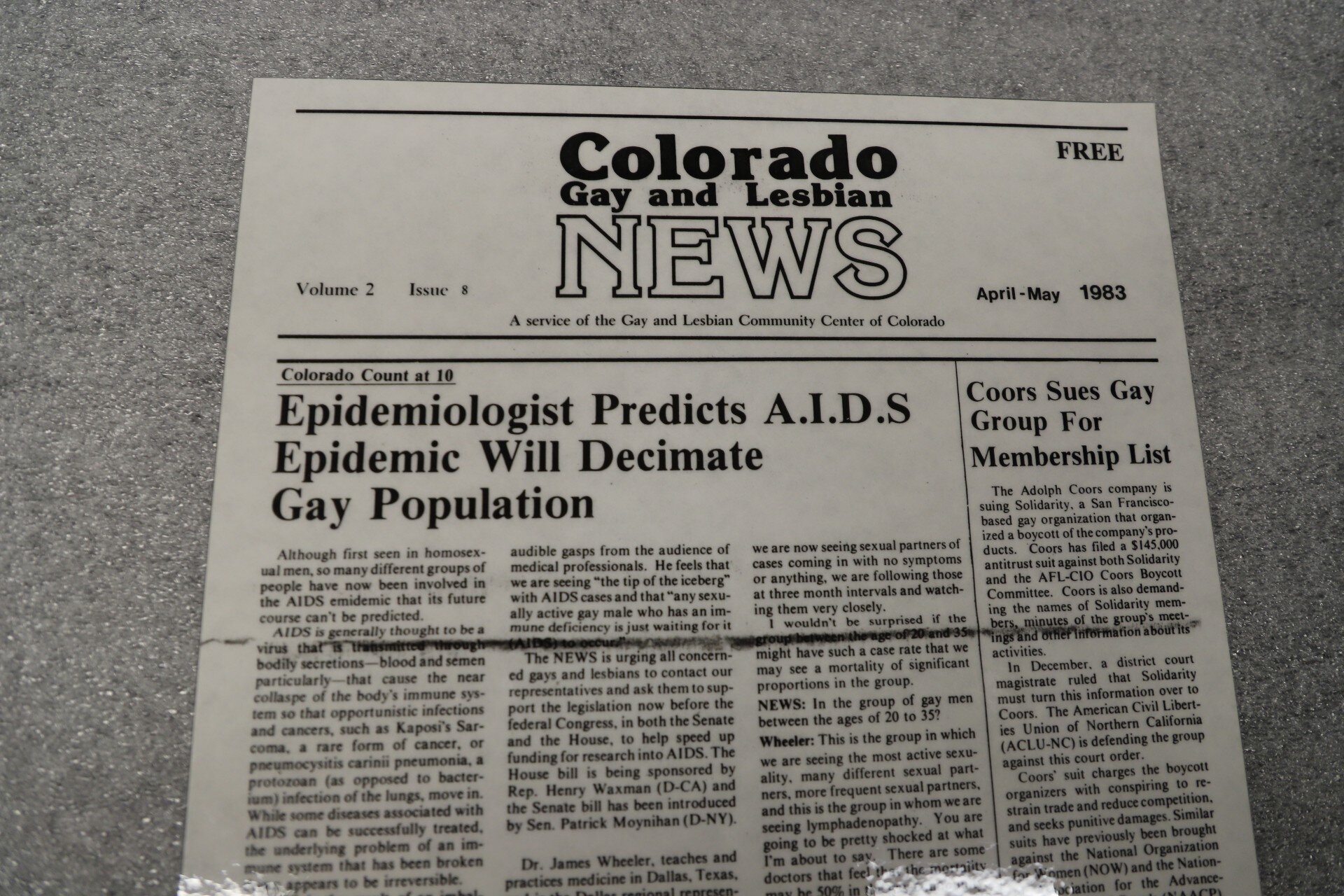

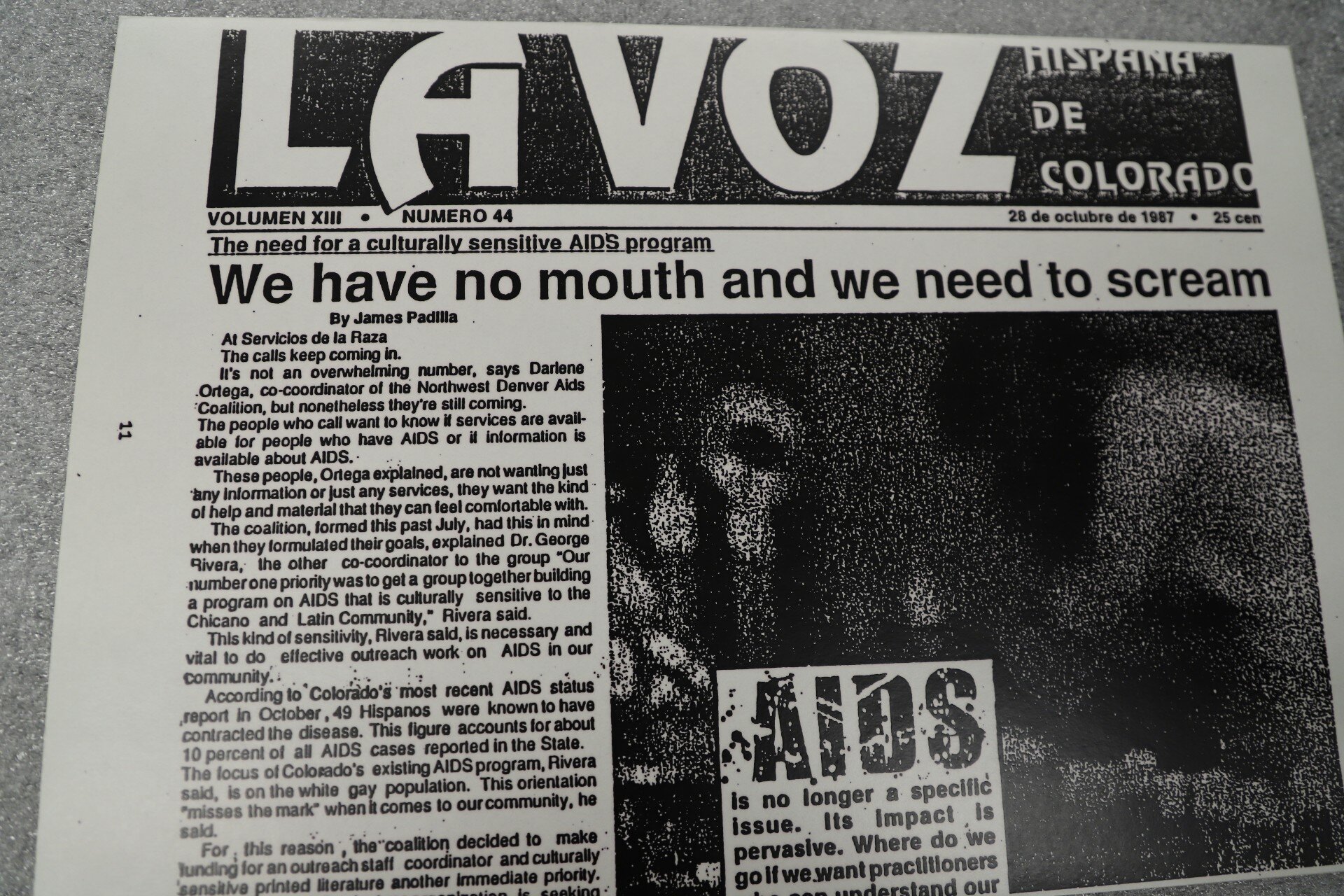

Aaron Marcus, the Gill Foundation Associate Curator of LGBTQ+ History at History Colorado, said even if the intention behind marketing information to gay and bisexual men is essential, it still brings back difficult memories of a time when he saw friends die of AIDS with no help or information from their government.

“It wasn’t that long after you started going out before the first person tells you they’re HIV positive, and back then it was a death sentence,” Marcus said. “Gay men were stigmatized within the community and definitely within the world at large.”

Marcus recognizes that the Biden administration and 2022 health officials are trying to avoid the ignorance and stigmatization of the past, but still can’t help but feel a sting when he sees two gay men in bed together on the website cover of a monkeypox information website.

“[AIDS] was very horrible because there was a stigma attached to it,” Marcus said. “Health professionals are trying to avoid that, but on their website, their illustrations are two men together, and what kind of message does that send?”

Alison Berg is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at alisonberg@rmpbs.org.

Related Story

Newspaper clippings at History Colorado show news coverage of the AIDS crisis in Colorado in the 1980s.