How Colorado is filling gaps as last-resort schools dwindle

Help is finally coming to Colorado’s facility schools, which often serve as a last resort for some of the state’s most vulnerable students.

A new state law will cut red tape and boost funding for the collapsing system, which serves children with intense behavioral, mental health or special education needs. The law also aims to train local teachers and staff, especially in rural areas, to serve such students closer to home.

While experts are hopeful, they acknowledged it won’t entirely fix the problems that led 50 privately run facility schools to close in the past 20 years, leaving just 30 open today.

“It’s a huge, complex system, and it’d be naive to think one piece of legislation is going to fix everything,” said Paul Foster, the executive director of exceptional student services for the Colorado Department of Education. “But the legislation is trying to take that into account.”

Lawmakers hope to see 12 new schools open in the next three years. But some of the likeliest candidates to become facility schools — small private programs that already serve students with disabilities — have said they’re not interested.

Meanwhile, public school districts have been starting programs of their own. But the new legislation does little to support these “missing middle” programs. The leader of one regional consortium said the state should be funneling money to them instead.

In a state that has long underfunded both education and behavioral health, there are gaps everywhere and no shortage of work to be done. However, there are also models, here and elsewhere, that point toward a better way to serve what can be a forgotten population.

New rules make it easier to form facility schools

The Learning Zone is a small specialized school in Littleton for nonverbal students. It’s in the process of becoming a facility school. It’s also a case study in how an irrelevant layer of bureaucracy can slow down that process — something the new law aims to fix.

Until now, specialized private programs had to become licensed day treatment facilities through the state Department of Human Services before the Colorado Department of Education could approve them as facility schools. The new law eliminates that first hurdle.

The Learning Zone teaches students who have rare genetic disorders and other disabilities to use devices that allow them to communicate by pushing buttons that convey words or phrases. It’s been a game changer for students who are often left behind in public schools.

“Some went from not reading to first-grade reading levels within nine months of being here,” said Amanda Attreau, executive director of Real Life Colorado, the nonprofit that runs The Learning Zone. “They actually get invited to birthday parties that are for their actual friends.”

But when The Learning Zone sought licensing as a day treatment center, it was subjected to a checklist of safety requirements and psychological goals geared toward an entirely different population: students with mental health issues and trauma.

“We had to become a day treatment even though all of the requirements of a day treatment don’t apply to our school or our population of learners at all,” Attreau said.

“You’re needing to check a thousand boxes for part one just to get to part two, even though the second box is the one that makes sense for you.”

Getting approval is important because school districts are more likely to pay for state-approved programs. However, the process was onerous enough that advisers suggested The Learning Zone wait for the new law to take effect. But Attreu feared losing students and money.

Districts that had been willing to pay part of The Learning Zone’s $60,000 tuition when it started as an alternative to remote school in 2020 had become “antsy,” Attreau said, and given The Learning Zone an ultimatum: become a legitimate school or we’ll take our students back.

“We don’t want the services we are offering to be limited to the people who are wealthy and elite and capable of paying for this,” Attreau said.

Not all private programs want to become facility schools

While state approval can be a powerful incentive, not all private programs say they want or need it.

School districts that once balked at the $96,000 annual cost for Firefly Autism in Lakewood are now more likely to pay, even though it’s not a facility school, said President and CEO Amanda Kelly. That could be due to a 2017 U.S. Supreme Court ruling. The high court found the Douglas County School District, which was refusing to pay for a student to attend Firefly, violated that student’s right to an education. It could also be due to Firefly’s 20-year track record.

“We have such a brilliant relationship with our districts,” Kelly said, adding that Firefly has students from 14 different districts. “I think that’s trust built over time.”

And Firefly doesn’t want to become a facility school, in part because it doesn’t see itself as a school. It doesn’t have teachers or students. Instead, the 42 children and young adults who spend their days there — who range in age from 3 to 21 and have a combination of autism and intellectual disabilities — are called “learners.”

They work one-on-one with certified behavior experts to learn life skills, chief among them how to communicate and advocate for their needs. Firefly is a day treatment program, but to become a facility school, it would have to hire teachers and a special education director and follow a curriculum aligned to state academic standards.

“To make such a massive change, we just don’t know if that’s what Firefly should do,” Kelly said.

Humanex Academy, a private middle and high school in Englewood, has another reason for not wanting to become a facility school. The leaders at Humanex, which serves neurodiverse students with autism, ADHD, and other disabilities, disagree with the goal of facility schools, which is to teach students the skills they need to return to public school.

“We didn’t want districts to say, ‘How soon can you fix them and give them back to us?’” Principal Kati Cahill said. “I always was a proponent of public education. But unfortunately the existing system isn’t set up to meet the needs of these kids.”

School districts filling the gaps with their own programs

Boards of Cooperative Educational Services, or BOCES, are regional associations of school districts that pool resources to provide a service they would not be able to alone.

Sandy Malouff is the executive director and special education director for the Santa Fe Trail BOCES, which serves six rural school districts in southeastern Colorado. Malouff started a day treatment program years ago because metro Denver facility schools were too far away, and students who did attend those schools often struggled to transition when they returned home.

The Southeast Alternative Learning Academy in La Junta serves students as far as 70 miles away. Over the past five years, about 30% of students have gone back to their local schools.

Malouff based her program on the Pikes Peak BOCES School of Excellence, which serves students who would likely need a facility school from more than a dozen districts around Colorado Springs.

Executive Director Pat Bershinsky said most districts would rather send their students to the School of Excellence “because they still have a connection to that kid. The kid’s not just put in a facility somewhere and forgotten about.”

In addition to the main location in Colorado Springs, a satellite location in the tiny town of Calhan puts services within reach for rural families. One student, Bershinsky said, had previously spent about four hours in a car every day going from Limon to a facility school in Denver. Calhan is less than an hour from Limon.

Bershinsky said lawmakers should have directed money to rural BOCES so they can “stand up their own programs like I have.”

Many metro area districts also have separate schools for students who struggle with behavior. In the Cherry Creek School District in suburban Denver, the Joliet Learning Center is often students’ last stop before going to a facility school or their first stop when they transition back, said Tony Poole, the district’s assistant superintendent of special populations.

But Cherry Creek is going further. Using $14 million in voter-approved bonds and $1.5 million of federal funding, the district is building its own treatment program that officials say is unlike any other.

Traverse Academy will serve 60 students in fourth through 12th grade in three separate wings: one for kids in mental health crises that will be heavy on therapy and light on academics, another for students with moderate needs that will balance the two, and yet another for students getting ready to transition back to their home schools.

Children’s Hospital Colorado and the University of Colorado Department of Psychiatry will provide clinicians to work alongside the educators.

Opening Traverse Academy this fall won’t eliminate the need for facility schools, Poole said, but he hopes it will alleviate some of the pressure, especially for students who are suicidal.

“With the closure of these facilities, we just have more kids in crisis who are left with no option,” Poole said. “It means we have kids in significant crisis walking our hallways every day.”

Advocates want more inclusion, not just more institutions

Some advocates say the real solution lies with helping public schools support students in traditional classrooms, not in creating more separate programs.

“When you build it, they will come,” said Diane Smith Howard, an attorney with the National Disability Rights Network. “What we have learned is: Anytime you create a program, the slots get filled. And they don't necessarily get filled with kids who want to be there.”

In California, the CHIME Institute's Schwarzenegger Community School in the Los Angeles area has been so successful at educating students with disabilities alongside peers without disabilities that CHIME staff provide technical assistance to schools and districts across the state.

If Executive Director Erin Studer could give advice to Colorado, it would be to fund model schools, “those bright spots of practice” that other educators can visit and observe, alongside a technical assistance center.

When students do go to specialized settings, supporting transitions back to their home school is critical. Teachers at Brook Valley South in Nebraska show teachers at students’ home schools how to carefully track behavior through the day and watch for patterns.

Teacher Carrie Fairbairn recalled one student who would run up and down the aisle of the bus badgering other students until they assigned him a seat behind the talkative driver who chatted the whole way to school.

“Lo and behold,” Fairbairn said. “Zero bus issues.”

“Sometimes folks are so quick to see that label on a kid: [emotional disability] or behavior disorder,” she added. “And you're like, ‘move his seat.’”

‘There’s nothing wrong with kids’

The story of Jack, a fourth-grader with autism, shows how short staffing in public schools can set off a spiral that requires more significant intervention. It also shows how tenuous progress can be and how critical it is to have a range of options.

Not long before Denver Public Schools recommended a facility school for Jack, his special education team thought he was doing so well in a separate classroom they wanted him to start going to the traditional classroom for math, his mother said.

But Jack’s elementary school didn’t have a one-on-one aide to shadow him, and the plan never happened. Disappointed, Jack returned to behaviors he’d mostly overcome: running away from school or refusing to go inside at all.

His mother, Heidi Laursen, lost her job — and her family’s health insurance — because she spent so much time trying to coax him through the schoolhouse door. The school called the police when Jack pulled a paper towel dispenser off the wall.

All last summer, Jack’s family thought he was on a waitlist for a facility school.

Instead, the Friday afternoon before school was supposed to start, Laursen said she got a call saying Jack would have to go back to the separate classroom at his old elementary school — the place that was short-staffed, that had called the police on him, and where Jack spent most of his time with the patient art teacher instead of learning.

“I couldn’t send him back to the school he had been running away from,” Laursen said.

So the family transferred Jack to Boulder, where his father lives. He was placed at Halcyon School run by the Boulder Valley School District.

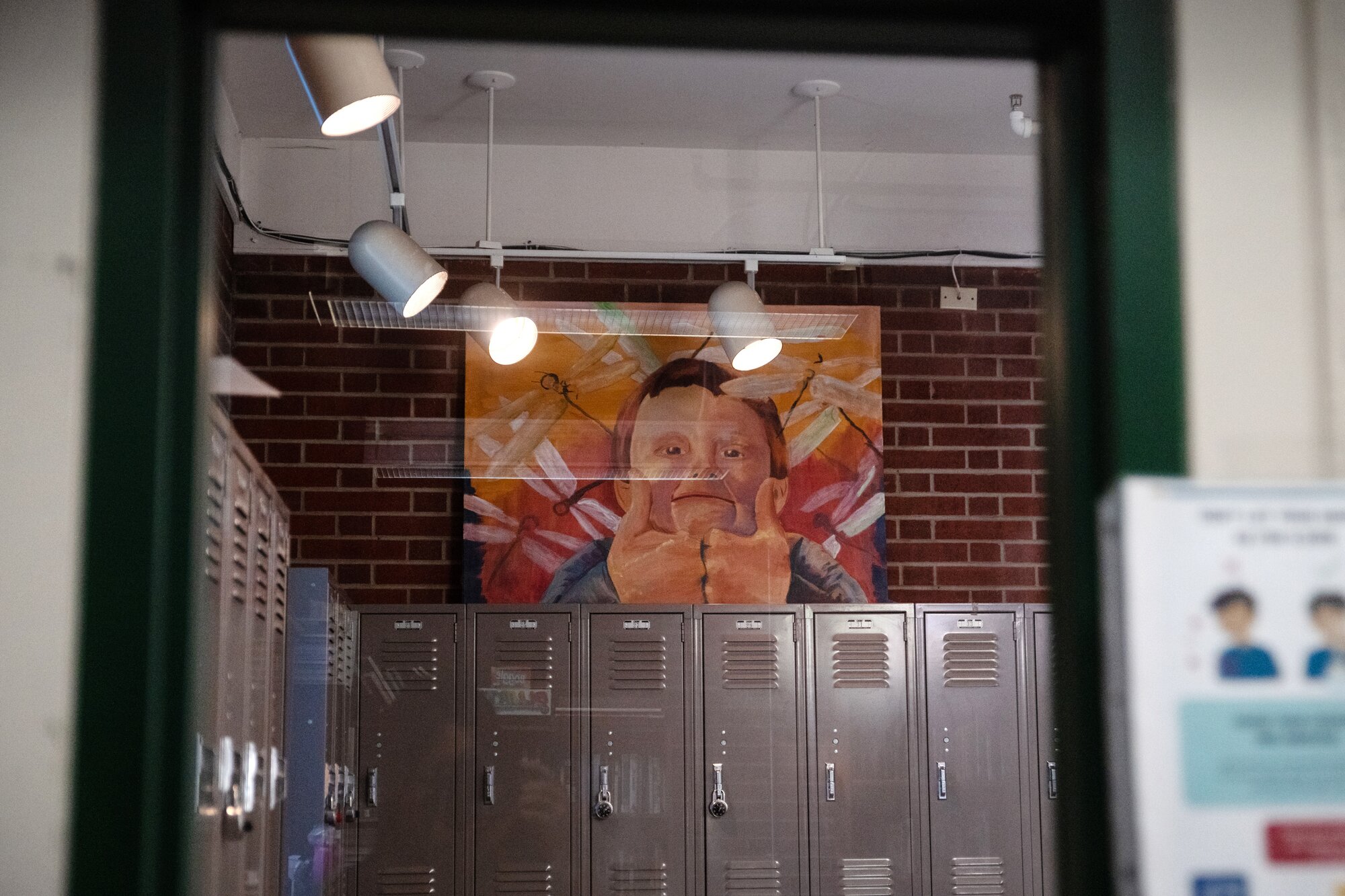

Principal Matt Dudek describes Halcyon as a small, safe space for students who might otherwise turn their frustrations outward or bottle them up to learn skills to manage overwhelming settings — like a traditional public school with hundreds of peers.

“We don’t fix kids,” Dudek said. “There’s nothing wrong with kids.”

The average stay at Halcyon is about a year. In 15 years, Dudek said he’s only referred one student to a facility school.

Jack’s fourth grade year has gone well, his mother said. Now 10, Jack has earned Matchbox cars and tiny Tech Deck finger skateboards for good behavior. When he’s overwhelmed, he has a “safe tree” outside where he can go, shadowed by a watchful staff member, until he’s ready to return to class.

Jack was doing so well that his team began talking about transitioning him back to a larger public school. Perhaps remembering the disappointment last time, Jack began acting out again, his mother said, running away or refusing to go into the building.

“In the end, we decided that maybe he wasn’t ready to transition, because of the behavior he was showing,” Laursen said. “Maybe he needs more time to feel safe.”