Colorado victims of predatory loans receiving $275,000 settlement after lawsuit against EasyPay

DENVER — By the time Andrea de la Garza realized that she had signed up for a loan with a 96% interest rate and hundreds of dollars in fees, it was already too late. It would take years for her credit score to recover and any of that money to be recuperated.

At the time that she fell victim to a predatory loan, de la Garza was a single mother to a child with Down syndrome. Her car — which she relied on for transport to regular medical appointments for her son, and for herself to teach barre classes all around Denver — needed repairs to its suspension system.

She went to a Midas auto repair franchise in Denver (at 341 S Colorado Blvd) and received a quote of just above $900 for work on the shocks and struts. But after a mechanic called and recommended additional repairs — several of which de la Garza said she never authorized — the cost ballooned to $4,400.

“$4,000 might seem like nothing to some people,” de la Garza said. “But to some people who need it and don’t have it, it’s devastating.”

The mechanic helped de la Garza open a new line of credit to pay for repairs that she couldn’t afford out-of-pocket, but she did not understand the terms of her contract. In a matter of days, de la Garza saw her credit score plummet from 680 to 450. Around half of the over $4,000 loan was in fees and interest.

That was in 2019. Four years later, de la Garza is finally seeing some degree of justice.

She is one of an unpublicized number of Coloradans who are splitting a $275,000 restitution payment from EasyPay Finance, a lender that offers easy-to-access loans through auto repair shops across the country.

The restitution is the result of a settlement reached in April, after the Colorado Attorney General’s Office found that EasyPay charged borrowers up to 199% interest rates on small-dollar loans ranging between $350 and $5,000.

Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser told Rocky Mountain PBS that EasyPay violated Colorado’s loan interest limit, which is around 36% — instituted in 2018 after voters overwhelmingly passed Proposition 111 to curb predatory payday loan schemes.

“Unfortunately, a lot of companies are always going to ask, ‘How can I get around that [36%] limit?’” Weiser said.

EasyPay Finance, which declined to provide an interview on this matter, did find a loophole in its lending practices in Colorado. Rather than providing loans with illegal interest rates directly to Coloradans, EasyPay facilitated a loan that originated at a separate lender (called TAB Bank), then purchased the loan and participation interest on the first business day following the funding date.

Because of that roundabout loan system, EasyPay was able to claim that they never gave loans with illegal rates to Coloradans. In fact, according to EasyPay, it gave no loans at all to Coloradans. They maintained that stance in the settlement agreement.

In a prepared statement to Rocky Mountain PBS, EasyPay Finance wrote: “EasyPay maintains that it did not make loans to Colorado residents and denies that the statute upon which the state was acting applies to these loans. Nonetheless, we were pleased to reach an agreement to resolve this matter."

Over a third of the loans facilitated through EasyPay had interested rates above 168%.

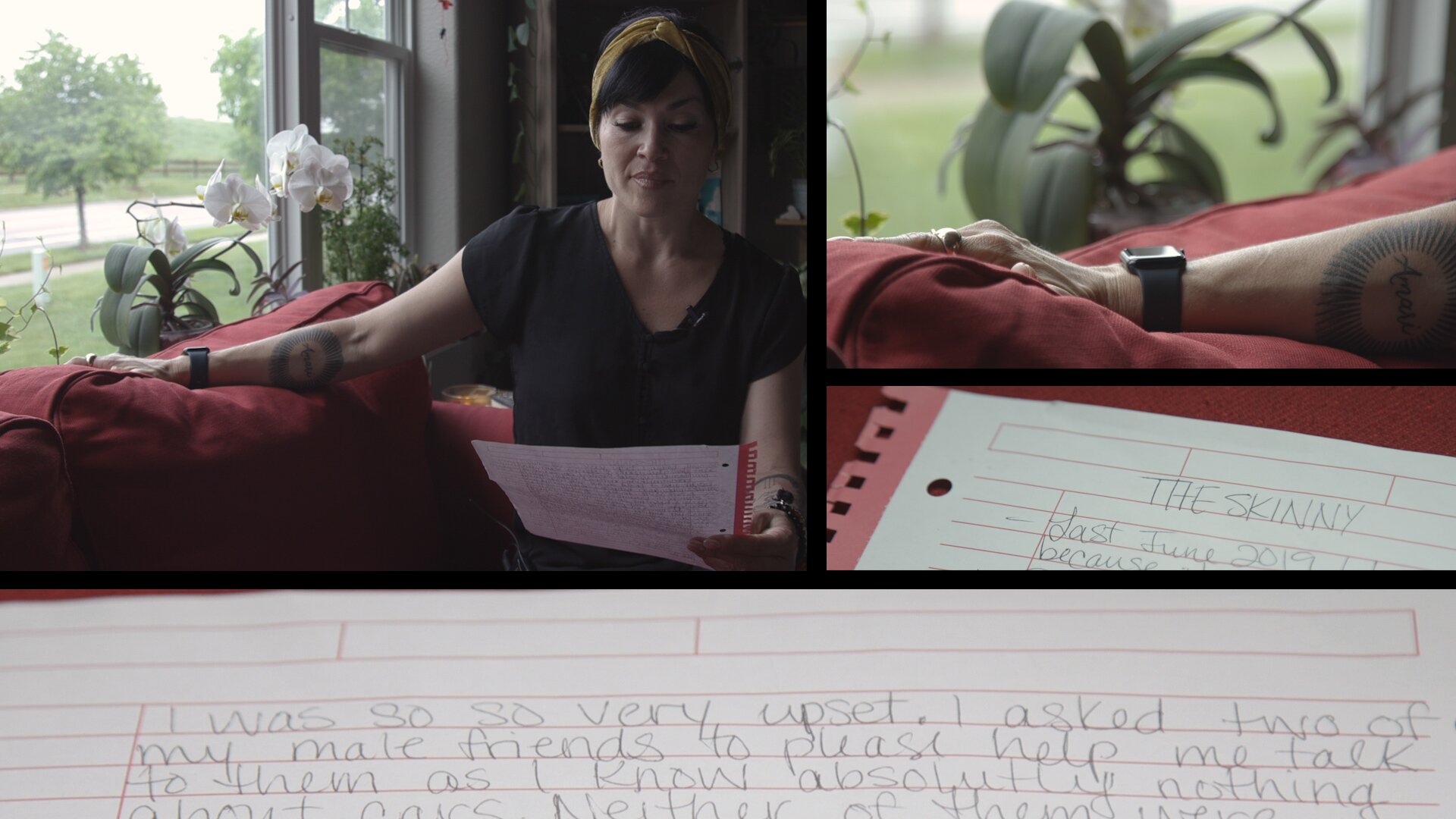

De la Garza reads a letter that she presented in small claims court, where she initially tried to recuperate the money she lost due to a predatory loan.

As a result of the settlement, Weiser told Rocky Mountain PBS that EasyPay will no longer do business in Colorado. He believes that the lenders knew they were putting vulnerable people at risk.

“You’re taking advantage of them,” Weiser said of EasyPay. “You know they’re gonna have a hard time paying, and you’re often putting them in a situation that, they’re not going to get out of this cycle of debt. It’s going to end up potentially in bankruptcy and have a whole series of collateral, negative consequences.”

For Andrea de la Garza, those consequences included years of financial and emotional strain, which overlapped with an unexpected, personal tragedy.

De la Garza said that the reason she initially signed a contract for a loan without reading the terms and conditions was that her son had trouble with sensory overload when he was in unfamiliar spaces. In order to prevent a potential outburst, she tried to limit their time in loud, new places — like car repair shops.

“Loud noises affected him. So if something was loud, he would panic or freak out and, in turn, he would act out,” de la Garza said, recalling that he was with her during each trip to Midas. “So I was kind of prepared to get in and get out of somewhere as quickly as possible.”

A few days after signing off on the loan, de la Garza finally read through the paperwork from the repair shop and discovered a list of repairs that she had never requested and a massive bill.

She immediately went to friends and family to borrow enough money to pay off the loan, recognizing that a 96% interest rate could easily get out of control. But the damage was done in other ways: with her credit score down in the 400s, de la Garza wasn’t able to sign a lease for an apartment in Denver without getting her father to co-sign.

She felt embarrassed and powerless.

“Who am I? Just this single mom. Unfortunately, I feel like also, I’m Mexican-American and sometimes we don’t have a voice,” de la Garza said. “What do I do? I feel trapped. I feel helpless. I feel small and insignificant and stuck.”

Most of the people de la Garza turned to for advice didn’t know what to do either. Her brother-in-law recognized that the interest rate was above the state limit. He recommended that she take Midas to small claims court in Denver.

She took his advice, but her claim was denied. She remembered the judge telling her that she shouldn’t have signed the paperwork, saying that “there’s nothing I can do about it.”

De la Garza made one final attempt to fight back by filing a claim with the Attorney General’s office. After a number of other Colorado borrowers filed similar claims against EasyPay, the state was able to target the lender with a lawsuit.

Years passed without de la Garza receiving any new information about her loan from EasyPay.

Then, on April 13, 2021 — while still waiting to learn if anything would come from the state’s lawsuit against EasyPay — Andrea’s son, Amari, died because of pulmonary hypertension. Amari experienced a cardiac arrest and was placed on life support for three days. He never recovered.

“He was my only child, and so it’s been pretty lonely,” de la Garza said, fighting back tears. “My whole world is different, you know? I never thought I’d be without him.”

Andrea de la Garza — one of the victims of EasyPay's lending practices — holds up a photo of herself on a hike with her son, Amari, who she lost in April 2021 as a result of pulmonary hypertension.

The financial strain of her loan happened to coincide with the most traumatic experience of her life. Although de la Garza was able to recover her finances over the past couple of years — she now owns her own barre studio — it’s been difficult to recover from Amari’s death.

“He needed so much all the time that, now I just have all this time and space. So I decided that I’m gonna open a studio so that I can have something to give all my time to,” de la Garza said. “But it’s only been two years, and I’m, I don’t know, lost.

Reflecting back on all the time she spent fighting to restore her credit and get her money back, de la Garza felt like nobody at Midas or EasyPay cared about the loan’s impact on her life.

For de la Garza, it’s hard to understand why nobody at Midas took responsibility for the scam.

“In a way, it’s just passing some crappiness from one person to another and not taking responsibility for ruining someone’s financial health and life,” de la Garza said.

De la Garza now owns her own Barre studio in Denver, after spending years recovering from a loan that wrecked her credit score.

Rocky Mountain PBS received no response to repeated requests for comment from ownership of the local Midas franchise or from Midas’ parent company, TBC Corporation.

EasyPay reported that 8,108 loans were provided to Colorado consumers through its convoluted arrangement with TAB Bank.

As a result of the settlement, EasyPay will no longer operate in the state of Colorado. Weiser hopes that this helps set an example for other predatory lenders in the state.

“We actually ousted this predatory lender from [Colorado],” Weiser said. “If you’re an irresponsible, unscrupulous actor, we will take action. We won’t let you operate in our state.”

Colorado consumers can report fraud of any kind to the Colorado Attorney General’s Office at StopFraudColorado.gov.

Zach Ben-Amots is an investigative multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach him at zachben-amots@rmpbs.org.