Hoofing it through the San Juans

Once they reach their grazing allocation, each permitted herd manager follows a rotational grazing plan designed toward a balanced forest ecosystem supporting plant diversity while reducing fire fuel. This forest hosts 83 cattle and sheep permits annually. The Valdez family is one of a few left who utilize a grazing permit for sheep.

The annual mountain grazing period runs from June through September, though shorter grasses due to drought and environmental conditions can push back the start date. In 2024, the sheep drive began Sunday, July 7.

The Forest Service meets with Valdez each year to determine the start window of the sheep drive and to plan the grazing rotation. Valdez and his shepherd, Dimas, will cycle the flock between three grazing areas within the allotment over three months. When the sheep come back down off the mountain, around 100 replacement ewe lambs are retained. Lambs that aren’t kept as ewes are sold at market. An average ewe, if kept, will make the annual trek seven or eight times in their life — that’s how the herd knows where to go.

On Sunday, the family and a few extra hands rise early and meet at the homestead ranch near La Jara to load sheep onto a waiting three-tiered semi trailer.The sheep are corralled into a succession of outdoor pens into a sectioned barn, where they walk up a chute onto the trailer.The sheep are driven about 40 minutes by semi to the first corral near the Devil’s Biscuit in La Jara Canyon west of Capulin, where they await an initial five-mile prairie drive to Jacobs Hill to spend the first night. It takes three semi trips to transport the flock to the holding corral.

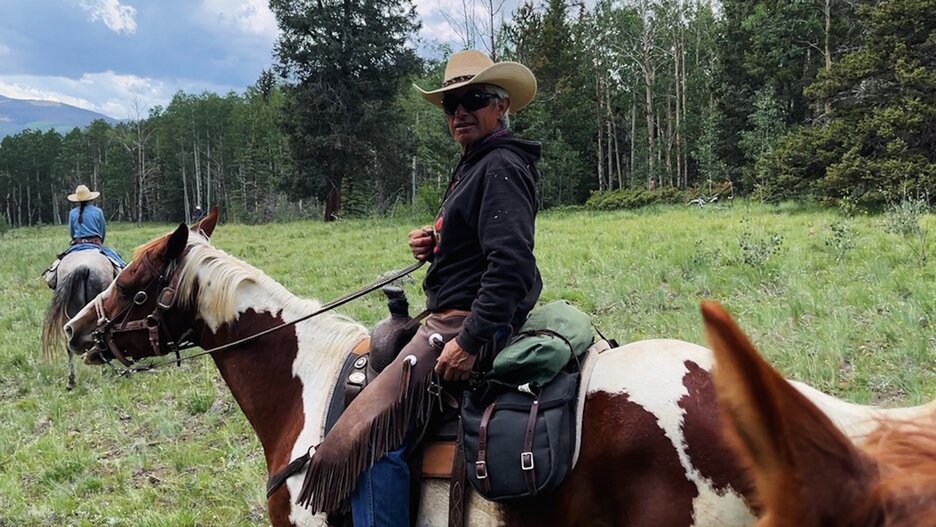

Dogs work tirelessly along the perimeter of the herd, traveling at the height of their energy to pace the sheep through the mountain terrain. Ranchers command the dogs with verbal cues and whistles, and shriek vowels in high-pitched voices to move the sheep along.Lost lambs, high timber jumps, deep ravines and thickly vegetated woodlands keep the canine pack occupied. At times, the drive grinds to a halt as a bottleneck or stray sheep cause the herders to pause.

Ascending rocky shale slopes move into deep, wide grassy down slopes inside a dense forest. Lush, rolling meadows are outlined by springs and creeks. Each day is paced with harsh riding and driving conditions followed by several hours of letting the sheep graze in large, high-altitude meadows. The sheep, dogs, horses and riders alike are able to recharge before the next leg of the journey.

As the sheep and dogs rest, horses and their riders are careful not to venture too close to the grazing animals. The dogs protect the sheep at all costs, which means barking at humans and chasing animals that come too close.

Each evening, the team arrives at a pasture where the horses are watered, fed, then staked overnight. Camp is made by extended family, most of whom are rider alumni. The family drives in at points on the trail to unload and set up camp, including tents, a kitchen, a water station, and a campfire, before the riders arrive.

After three nights of camping on the outskirts of forested meadows, a final half-day jaunt high above Platoro brings the team to the first rotational pasture. The sheep are released to graze on the permit for the first time this year. Valdez and the shepherd confer on a grocery list, and the shepherd is left with two dogs, two horses, a tent, a wood stove, tools, feed and supplies. Valdez will make frequent visits until the herd is moved to the next pasture rotation in two to three weeks.

The sheep drive is an honored tradition in the Valdez family, with many of this year’s riders having gone on their first ride in their single digits. It is not uncommon for a five or eight year old to be put on the back of a horse to scale the mountain for their inaugural trip. Valdez himself has been going on sheep drives with his family since he was a little boy.

“Next year,” his five-year-old grandson said with a time-honored pride, “I’m going to ride on the sheep drive.”