What’s the big deal with Manitou’s mineral springs?

share

MANITOU SPRINGS, Colo. — When the rattling of coffin races or the whizzing of fruitcake tosses eventually dies down, the small town of Manitou Springs fills with a gentler, yet equally as distinctive melody: the trickling of mineral springs.

For millennia, the mineral springs have both literally and figuratively made an indelible impression on the town, shaping the area geologically, economically and culturally.

“The mineral springs [are] the soul of our community,” said Doug Edmundson, a fourth generation “Manitoid” and the sitting president of the Mineral Springs Foundation, a nonprofit committed to preserving and protecting Manitou’s public springs.

The springs’ novelty faded during the early 1900s. As some of the town’s once flourishing bottling companies began declining, the springs they relied upon were either neglected or capped and diverted to avoid excessive water runoff into the streets.

A group of impassioned locals joined to form the Mineral Springs Foundation in 1987 with the goal of identifying, restoring and re-invigorate the town’s namesake water features.

While there are dozens of natural springs flowing around the town, there are currently eight springs open to the public, most of which run through “fonts” (fountains) that dot Manitou’s main street, Manitou Avenue.

The fonts are operated by the Mineral Springs Foundation. Because each spring flows with different strength, fonts are manually contained and controlled. If left unmanaged, some streams from the springs would be coming too fast to safely taste, said Edmundson.

Manitou’s springs have been continuously running for many centuries, and they will continue running unless otherwise obstructed or redirected.

Some springs are still privately-owned, like those used at the SunWater Spa Manitou Springs, while others were capped and diverted long enough ago that they can be somewhat difficult to find.

The Mineral Springs Foundation is working to identify and make public these springs while publicizing their importance to the community in the most Manitou of ways: by organizing a quirky public festival.

The Mineral Springs Foundation recently held its second annual Waterfest celebration with an afternoon of mineral water-ccentric party hosted in Seven Minute Spring park.

Larry Cesspooch, a Ute spiritual leader, opened the festival with a speech and ritual prayer describing the significant role water plays in Ute culture and tradition.

“Water is life,” said Cesspooch. “The Creator takes Water and Earth and combines those to make this body.”

“It’s water that’s inside of us and keeps life going.”

Visitors enjoyed a variety of mineral water-infused activities such asa mineral water ice bath, a mineral water slip-n-slide and a mineral water dunk tank. Two water mascots, Gaga and Wawa, also made an appearance.

While the springs have played a role in his and his families’ lives for decades, Edmundson noted that their origins date back far beyond his personal history.

Manitou Springs’ unique geology provides the specific setting needed for natural mineral springs to form. The stone formations lining the box canyon that surround the town of Manitou are complex composites of Pikes Peak granite, dolomite and sandstone, among other rocks and minerals.

Over thousands of years, slightly acidic rainwater gradually seeped through semi-porous layers of limestones via various fractures and joints. These leaks eventually carved out small pockets within the subterranean rock.

This process of creating underground concavities, many of which then filled with water, created artesian aquifers, pressurized underground wells named after the Ancient Roman city of Artesium where such wells were tapped during the Middle Ages.

Artesian aquifers exist nationwide. What makes Manitou Springs more unique is the incredibly high carbon dioxide content present around this underground water.

According to the Mineral Springs Foundation, some measurements of the gas by volume at the springs reaches as high as 99%; that’s compared to the less than 1% usually found dissolved in shallow groundwater.

While the Mineral Springs Foundation suggests that much of this carbon dioxide originates from Earth’s outer mantle, it’s this natural carbonization that helps send the springs from their aquifers all the way to the fountains to the surface.

The water trickling through the karst landscape combines with carbon dioxide released from the surrounding dissolving rock layers, in turn producing carbonic acid (H2O + CO2 = H2CO3).

This carbonic acid creates the natural soda-like water that, with the help of strong underground pressures, is forced to the surface through narrow fissures and joints in the rock.

While such natural phenomena are rare, other naturally carbonated mineral springs exist, including in the small Idaho town of Soda Springs, which also advertises its defining feature through its name.

Edmundson noted that there may have been more than 50 springs running throughout the valley when Manitou Springs was founded in 1872. However, he underlined that these waters were socio-culturally significant well before the town incorporated.

“We have to go back to the indigenous peoples of the area,” said Edmundson. “The Ute, the Tabeguache, the Cheyenne, the Arapaho and other tribes.”

Gradually, western settlers began to populate the area. They quickly took to the springs, using the water to bathe, drink and eventually sell.

Popular science at the time began to spotlight natural mineral water like that found in Manitou Springs as beneficial for one’s health, sparking 19th-century health-crazes and drawing visitors from across the nation.

“There was a bit of debate that mineral water was as good for you as hiking around in the fresh air and sunshine,” said Edmundson.

This spring-fountain fervor led enterprising locals to begin bottling the spring water, thus forming what Edmundson deemed as possibly Manitou’s only real industry, apart from tourism.

Bottlers even began bottling and selling carbon dioxide emanating from the springs.

Manitou water began appearing on tables across the country, said Edmundson, and bottlers such as the Ute Chief Bottling Works began mass-producing a myriad of drinks incorporating the mineral waters, including Pale Dry, Lime Rickey and Ute Kola.

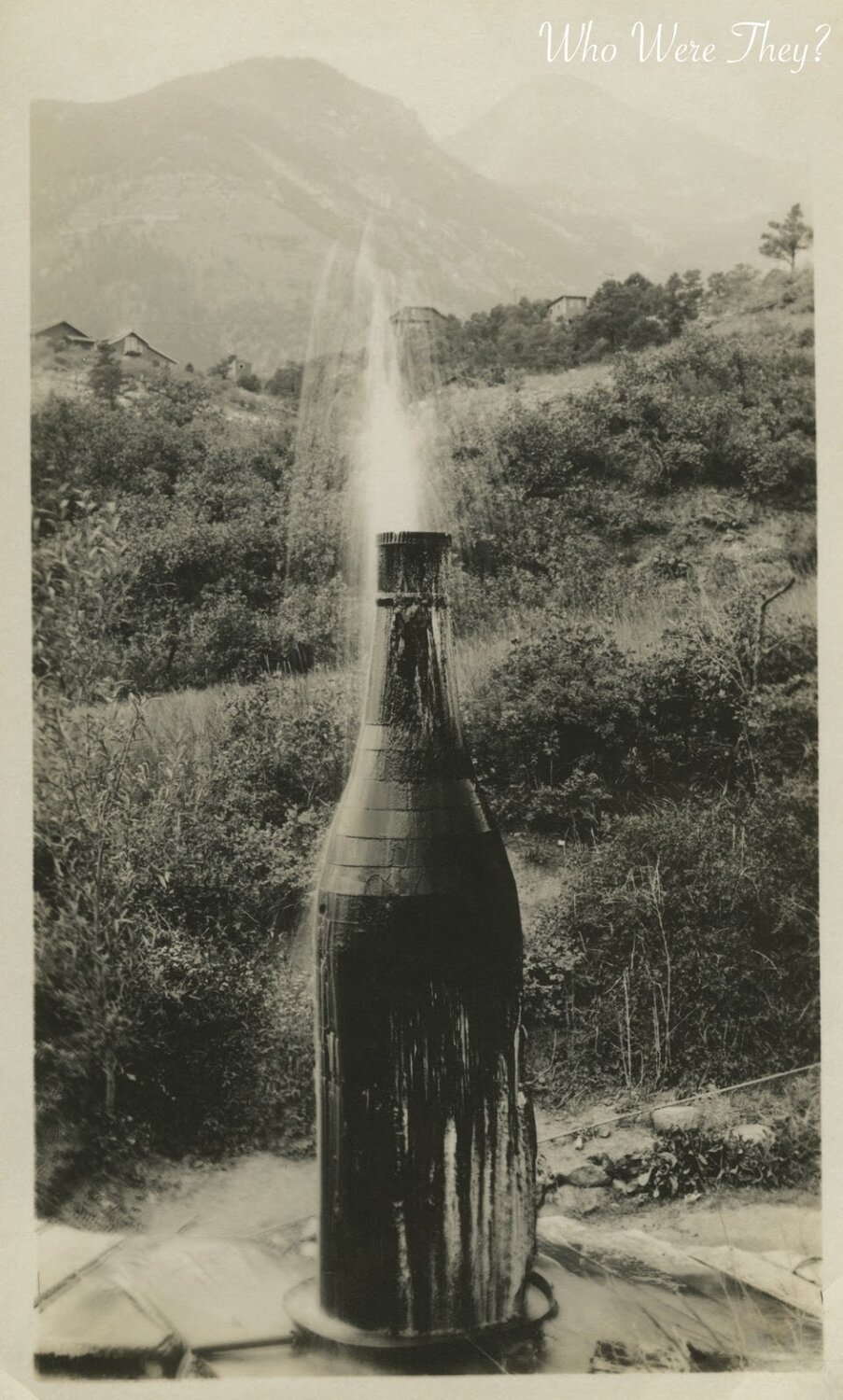

At one point, the Ute Chief Bottling Works placed a promotional bottle — known at the Ute Chief Gusher Bottle — over the top of a then 48+ foot geyser spouting near the end of town. The geyser was capped and diverted when its commercial use was finished.

The bottle disappeared in 1914 and was re-discovered in a ditch by a few Air Force cadets only a few years ago.

Edmundson was fortunate to catch wind of the badly damaged bottle. After a restoration, the promotional bottle is now on display at the recently opened Manitou Springs Heritage Center and Museum in Manitou Springs, along with a glass case full of Ute Chief bottles.

The Ute Chief Bottling Company and the mineral spring table water industry has almost entirely disappeared in the town.

However, the industry made enough of an impact to influence the town’s name.

According to Edmundson, the valley now known as Manitou Springs was originally called “Le Font Bout” (French for “The Boiling Font”). Indigenous names have been lost.

The town’s name changed first to just “Manitou,” which comes from the Algonquin word meaning “great spirits.” However, the name caused some confusion and mail mix-ups due to its similarity to names like Manitoba, said Edmundson.

The “Springs” was added by the town’s official incorporation in 1876, denoting the town’s reputation as a health and wellness resort town.

Colorado Springs was a fountain colony, called the Font bayou, then named just Manitou but problems with mail going to Manitoba without the Springs, some problems so renamed to manitou springs.

Many of the original springs still run wild around different parts of the city, and some have since been covered, capped or diverted to avoid run-off or for private land use.

The Mineral Springs Foundation currently stewards eight of Manitou’s public springs. Founded in 1987 by a reputable “who’s-who” of Manitoids, according to Edmundson, the foundation has since worked to construct, preserve and protect the “fonts” (fountains).

These eight include (from the southernmost to the northernmost): Seven Minute Spring, Shoshone Spring, Navajo Spring, Cheyenne Spring, Wheeler Spring, Stratton Spring, Twin Spring and Iron Spring.

Seven Minute Spring is named for the amount of time it takes the water to run from the underground aquifer to the font. Wheeler Spring and Stratton Spring are named for influential town members.

And Iron Spring is named for its waters’ distinctive metallic taste.

According to Edmundson and Mineral Springs Foundation board member Taylor Trask, who served samples of spring waters at Waterfest, each spring has its own distinct flavor due to the minerals collected during the water’s passage through the underground fissures.

“Twin [Spring] and Wheeler [Spring] are probably the most middle-of-the-road waters,” said Trask. “Twin is our most favorite… that one folks like to make lemonade out of.”

Stratton Spring has a bit more of a “punch” and a little spice, according to Trask, while Iron Spring’s sharp metallic tones tend to be a bit more divisive. Trask and Edmundson both added that most tasters, even within families, have different preferences.

“Everybody’s palate is different,” said Trask, “So I say try them all, find your favorite and come back any time.”

Tourists to Manitou Springs stroll with small Dixie Cups in hand for a springs tasting tour. Signage near each spring cautions tasters about the mineral content in the springs.

Despite the recorded presence of some minerals that might be potentially harmful if consumed in excess (such as manganese) in some of the water, Edmundson assured that each spring is safe for tasting.

“We test every month for bacterium, nitrates… [we do] a full profile of safety testing as they do with your tap water,” said Edmundson.

The Mineral Springs Foundation has recently been working with the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment to educate the public that tasting the waters is safe.

But Edmundson still suggests that consumers keep to just a taste, a not too much more.

The Mineral Springs Foundation plans on continuing to refurbish the existing fonts and is actively looking to retain public ownership over other privately-owned or currently unprotected springs, all with the hopes of allowing visitors to continue enjoying the city’s namesake natural wonders.

Edmundson is proud to be preserving the legacy of the springs, which have become integral parts of the lives and histories of life-long and generations-old Manitoids.

“Manitou Springs is a wonderful small community where things really pick up in the day, and it kind of becomes almost a sort of living, breathing street fair carnival,” said Edmundson.

“And then late at night as things settle down, and it’s dark and cool… you walk through town, and it’s quiet… and you can literally hear the springs running and spraying throughout the town.”

“It’s really something unique and special.”