Local foresters use trees to combat extreme heat in Denver's historically underserved neighborhoods

DENVER — In Denver’s Athmar Park neighborhood on the west-side of I-25, just south of West Alameda Avenue, residents cherish the area’s comforts — including its greenery.

“I love living here. We have a park just down the street. We have two schools. We have a library and a rec center not too far away,” said homeowner Mark Villegas.

Across the park about a mile away, Laura James shares similar sentiments about her neighborhood.

“We really like the charm of the neighborhood. We like being close to the park…all of the big trees that have been here for a while,” she added while standing under the shade from the one large tree in her front yard. But on the south side of her yard, the sun was beating down without much shade.

As summers continue to get hotter and heat waves become more common due to climate change, any form of shade is welcome. So, when offered a chance to have more trees added to their neighborhood, specifically their yards, both Villegas and James quickly said “yes.”

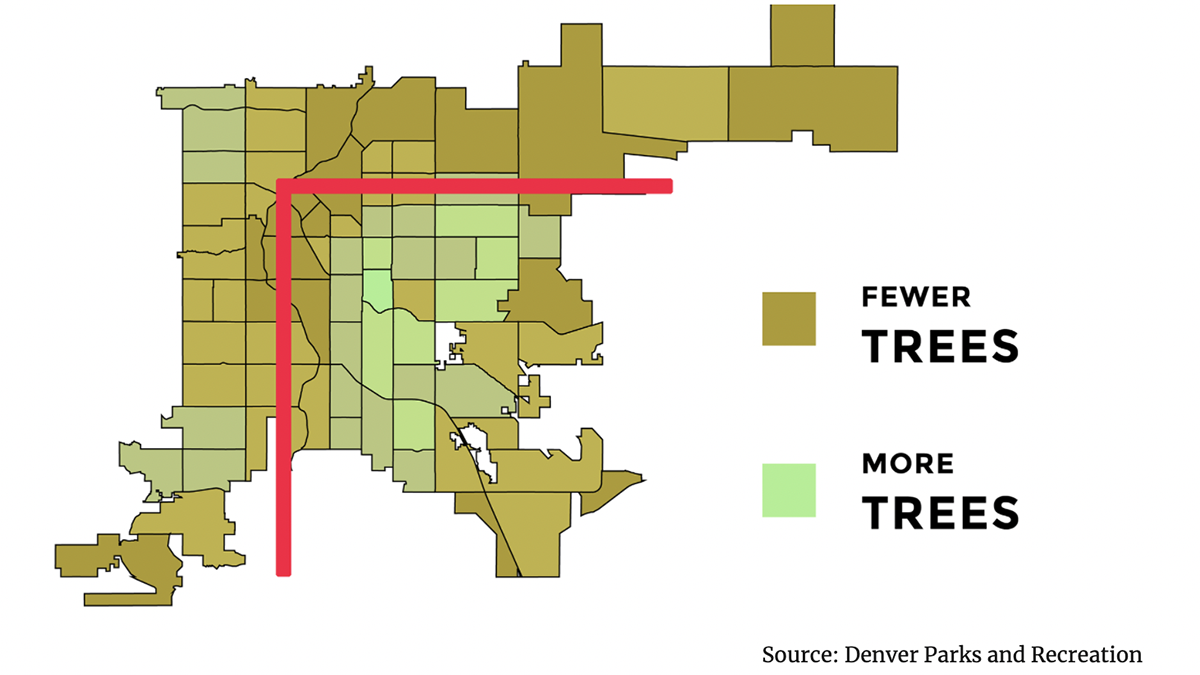

The Athmar Park neighborhood is part of the Forestry Neighborhood Initiative (similar to Downtown Denver's Urban Forest Initiative) to bring more greenspace — in the form of trees — to historically underserved communities throughout the city. Here, homes are in what has been called the ‘Inverted L’, a large collection of neighborhoods that line the main highway hubs along I-25 following the South Platte River north to I-70. This area is a highly industrial and urban zone now, but it wasn’t always that way.

About 100 years ago Denver's Valverde neighborhood—Spanish for "green valley"—was predominately a farming community.

“Fast forward to the 1950s and 1960s when urbanization and industrialization comes about pouring more asphalt and more concrete. Then, they build out I-25, Federal Boulevard, and 6th Avenue,” explained Mike Swanson, a longtime forester for the City and County of Denver.

“It just became a physical and psychological barrier. Hence, the 'Inverted L,'” he said.

But for Swanson and Denver’s Office of Forestry, adding trees is one way to help immediately, as well as in the future.

“Trees – they’re living and are part of our community. [Trees] cool the air, cleans the air, slows down the rainfall,” explained Swanson, who has worked with the city for more than 30 years. “It's really about the livability of your city and your neighborhood, your communities. That's just the greater common good.”

“It’s pretty darn hot, right?” Swanson asked on a sunny July afternoon in Denver’s Baker neighborhood. The sun was high overhead, and the ground was heating quickly — a phenomenon also known as the heat island effect.

“The sun hits these impervious surfaces: asphalt, tops of the buildings, streets, sidewalks. And it just stays there. It doesn't reflect off. It just stays there. So, everything around it just gets hotter and hotter and hotter,” Swanson explained.

“And because of that, urban areas are a lot hotter than suburban areas," he continued. "If you went 10 miles east of here it would be a little cooler, as long as there are trees, which reflect the sunlight and cool down the air.”

To reinforce his point, Swanson suggested walking to a shaded area, about 20 yards away under a 40-year-old Austrian Pine and Honey Locust tree where it was noticeably cooler.

“Cooler, huh? It's about 15-20 degrees cooler easily, right?”

According to Swanson, the shadow footprint of an American Elm (about 40-years-old) is at least 60 feet wide. This would help cool the home that was shaded and give some relief to nearby buildings experiencing heat island effects.

“What's important is the shade or the shadow. The leaves [themselves] are good for [slowing down] rainfall absorption…So it gets into the soil, gets into the ground,” he said.

This summer, the Forestry Neighborhood Initiative focused on southwest neighborhoods like Athmar Park with plans to move north. Through the program, the initiative has already delivered 100 free trees to local homeowners.

Back in the Athmar Park neighborhood, James received two trees from the city—a Northern Catalpa and a Kentucky Coffeetree. Planted on her birthday a few months ago, both trees are doing well. James believes the greenery will help her entire community.

“I think being proactive is so good. If we waited until there were the fewer trees or the older trees got disease…I think it's much better to start it now,” she said.

Villegas received a Northern Catalpa which he planted near his sidewalk. By receiving the trees through the initiative, both homeowners saved hundreds of dollars.

Villegas said the arborists told him the tree was valued at $300 and that delivering it and planting it would have cost another $200, none of which Villegas has to pay.

"That alone was quite a surprise,” said Villegas. His new tree is already providing a bit of shade.

“It's amazing to see how fast is has grown. It seems like its happy to be here.”

Swanson is hoping the enthusiasm he has seen from Villegas and James will encourage other homeowners to learn about trees and natural resources in their neighborhoods that can improve Denver’s heat island effect.

“I get that there's other considerations for the family dollar. But there’s an old Japanese saying: ‘Planting a tree, you’re planting life,’” he said, adding that this is one of the easiest ways to invest in your community.