The Other: The Harmful Legacy of Human Zoos

Colorado Experience: The Denver Zoo airs April 15 at 7 p.m. on Rocky Mountain PBS.

DENVER — The harmful exhibition and practices displaying humans that are known today as “Human Zoos” took place for centuries, and their impact can still be seen today.

Colonial exhibitions and fairs, circuses, zoos, and museums all took part in exhibiting people from across the world that were deemed other and, thus, curious to observe by white masses that deemed themselves superior and more civilized. In some cases, entertainment was elevated through the incorporation of thrilling performances and the display of exotic animals, further animalizing and dehumanizing exhibited humans.

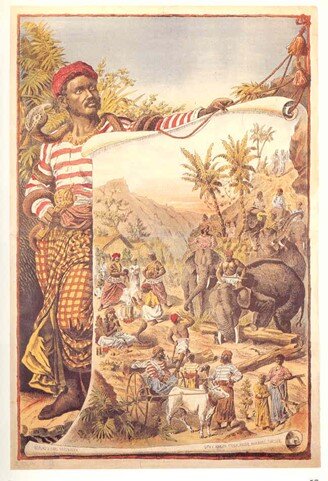

Posters advertising Hagenbeck’s exploitative exhibits with the Sámi people of northern Europe and the Sinhalese people of Sri Lanka.

One of the most influential individuals in this exploitation was a man named Carl Hagenbeck. While he is mostly known for his impact on zoo architecture, he was also a prominent wild animal trader and trainer, and an “ethnographic showman.” Along with large names like P.T. Barnum, he further popularized “Human Zoos” at the turn of the twentieth century.

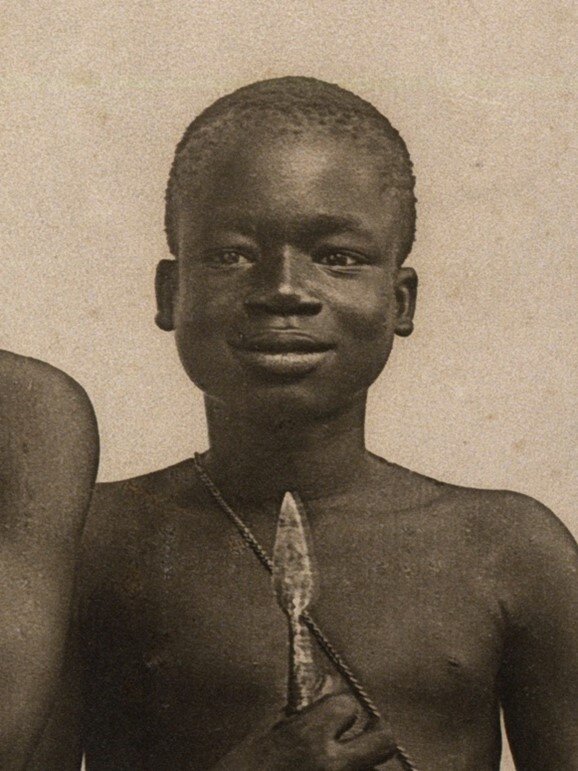

One of the most infamous exploitations of an individual involves a young man named Ota Benga. In 1904, an American missionary and explorer was hired by the St. Louis World’s Fair to “acquire” an African pygmy to the fair for exhibition. Benga, from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then known as the Belgian Congo, a colony of Belgium), was purchased by the missionary from the Baschelel tribe for “several bags of salt and a spool of brass wire,” according to an interview with the missionary’s grandson, likely at a slave market (another product of colonization).

After being exploited at the fair without pay, the missionary returned Benga and other captured African Pygmies to their home. But when he discovered that all members of his tribe had since been killed, Benga did not feel at home and asked to return with the missionary to the U.S.

Subsequently, William Temple Hornaday, then Director of what is known today as the Bronx Zoo, inquired with the missionary if he could exploit Benga to maintain the elephant enclosures. Over time, Hornaday discovered that people were coming to see Benga and thought that exhibiting Benga would be a great opportunity. It is reported that up to 40,000 people came to the zoo every day to see Benga in a cage or doing the odd task.

Through the efforts of a group of Black ministers, the Bronx Zoo closed the exhibit and Benga was released. He was moved to Brooklyn and then Lynchburg, Virginia where a number of families housed him, and tried to "educate" him and lead a "normal" life.

In March of 1916, Ota Benga ended his own life.

Over 100 years later, the Wildlife Conservation Society, which manages the Bronx Zoo, issued an apology.

Such exploitations were pervasive, even in Denver.

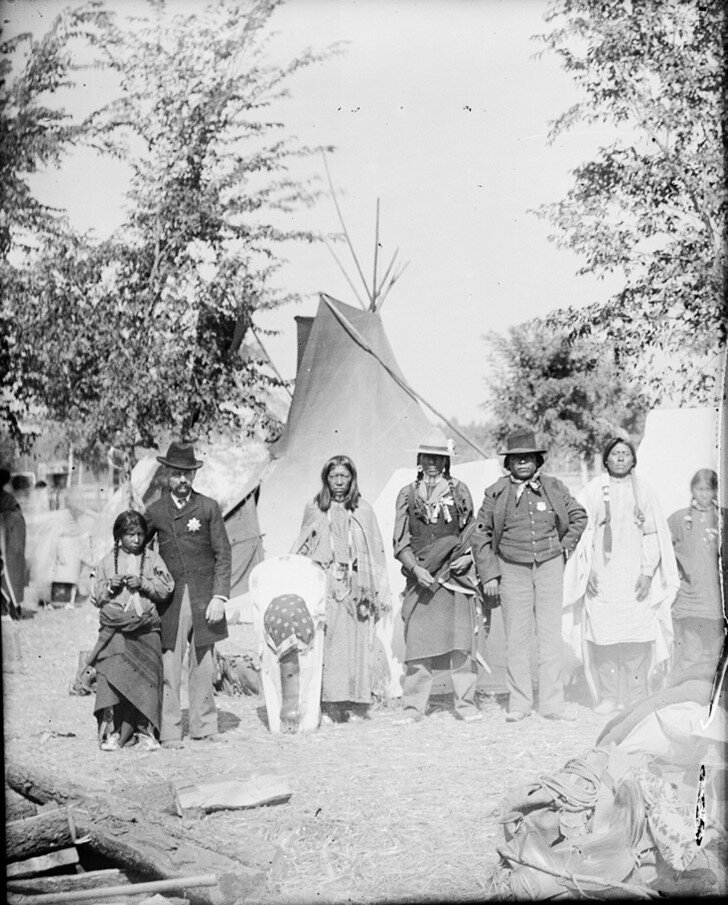

In 1900, the Denver Zoo was four years old. Owned by the City of Denver, it occupied a corner of the newly established City Park and exhibited a small collection of local hoof stock, birds, and other furry mammals—stitched together by delicate fences and simple cage-work.

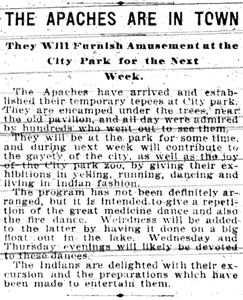

That year, the city brought members of the Jicarilla Apache Nation, referred to as the “Wild Apaches,” to City Park. The emerging zoo served as a backdrop for their encampment.

The History Colorado Stephen H. Hart Research Center was able to help Rocky Mountain PBS uncover articles from the time to provide more information.

According to newspaper articles, a Colonel C. E. Ward was recruited to “obtain permission for a band of the warlike Apaches to visit Denver.” For nine days, the “party of twenty Apaches” gave “exhibitions of village life” at City Park.

Further, one article stated, “weirdness will be added to the latter by having it done on a big float out in the lake.”

The perceptions rooted in the concept of the “Human Zoo” survive today. From human safaris to referring to Black, Indigenous, and people of color as “exotic,” whiteness continues to be centered, oppressing anything deemed other. This concept would pave the way for eugenics and pseudoscience racism.

Preconceived ideas about “civilized versus savage” people—the animalization of people—would help shape scientific racism, just one insidious operation of systemic racism that persists today.

Resources:

To read further:

- Superior: The Return of Race Science by Angela Saini

- The Denver Zoo: A Centennial History by Carolyn & Don D. Etter

To watch further:

To listen further:

Colorado Experience | The Denver Zoo