Street art energizes Knob Hill Urban Arts District

The popularity of street art as a force to augment and signify neighborhoods is growing nation wide — and Colorado is in on the movement.

For one weekend during each of the last 11 years, artists transform nearly every outside surface area in Denver's RiNo Arts District during CRUSH Walls, painting huge, intricate, colorful murals. This year, at the end of September, muralists crossed oceans and state lines to participate in the event, creating 60 enormous, eye-catching, place-making works of art.

An hour south on I-25 in Colorado Springs, two miles east of downtown, a group of artists and community organizers followed suit. Inspired by the enthusiastic attitude of their northern contemporaries, the Knob Hill Urban Arts District collective is pouring their hearts into a similar vision.

Three years ago, a dream of invigorating a forgotten neighborhood defined by pawn shops and a stark stretch of urban highway led artists Paes and Muji Rieger to work with local business owners to fill what they call the “public art void.”

To date, individual artists and teams have painted upwards of 50 murals along a one-mile stretch.

“Outside of downtown, which does a great job, there is a void of public art in Colorado Springs,” says Rieger, Executive Director of the Knob Hill Urban Arts District.

Like CRUSH, the Knob Hill Urban Arts District partners with local businesses to pinpoint exterior building walls -- to artists, they are giant, blank canvases. But unlike CRUSH, which has additional allocated funding from business and property taxes, the Knob Hill crew has no formal source of funding.

“Colorado Springs does not have a funded public art program, and has no real overall process for public art," says Knob Hill Urban Arts District Community Coordinator Brian Elyo.

But that hasn't halted a collaboration.

"We're actually working with the City as they finalize an Arts Master Plan to pilot programs that are a part of local infrastructure," Elyo says.

The group is also working to gain state certification as an official Colorado Creative District through Colorado Creative Industries. Creative Districts are designated hubs recognized for attracting creative entrepreneurs to a community while infusing new energy and innovation.

"We’re right in line with the Downtown Colorado Springs Creative District and the Manitou Springs Creative District," says Elyo. "It will be a giant Creative Corridor."

The neighborhood's main throughway, Platte Avenue, "is also a main corridor for tourism," says Rieger, "for people going to the Air Force Academy, downtown, Manitou Springs, and Old Colorado City. We want to establish ourselves as a unique neighborhood right here, with unique traits.”

The Knob Hill neighborhood itself dates back to the 1890s.

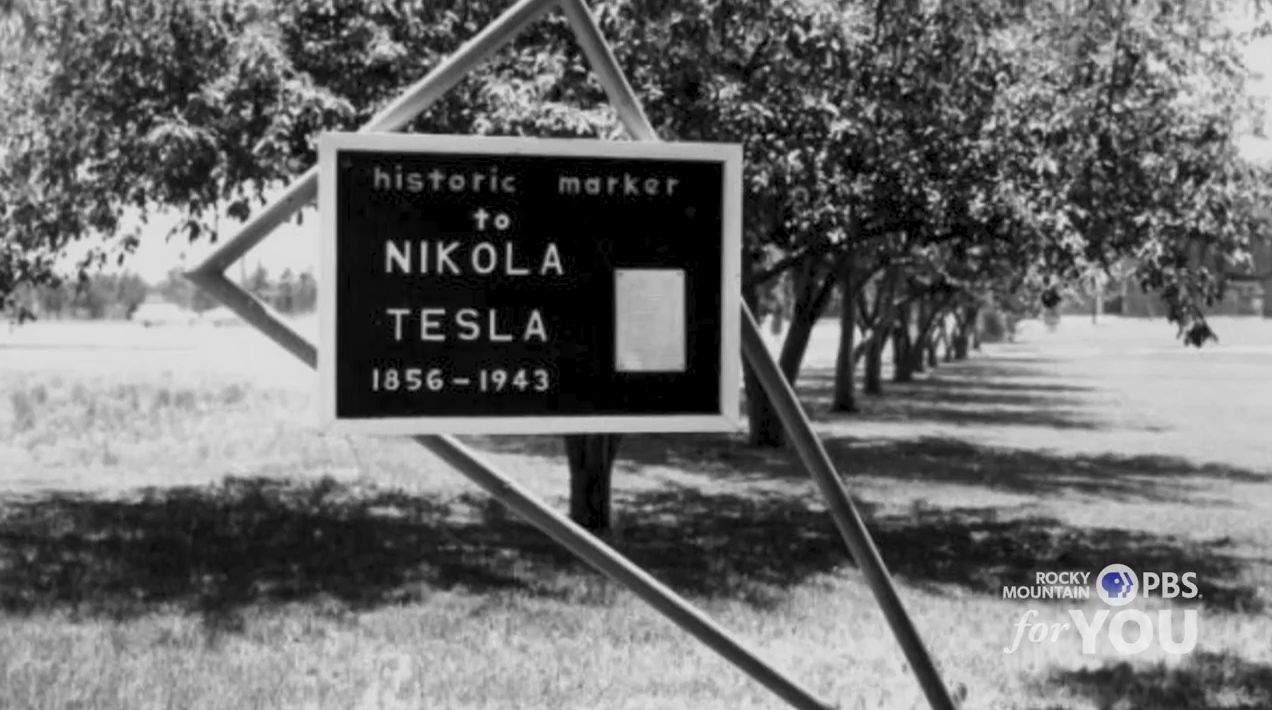

“Famously, Nikola Tesla had a science station in Knob Hill,” says Elyo. “When he references it in his writing, it was a literal, physical hill that was called Knob Hill.”

Over time, the neighborhood, once the eastern edge of town, was annexed into the city.

“The City actually used to stop at Knob Hill's westernmost boundary. You were kind of out of town at that point,” Elyo says.

The country flavor is still evident in at least one way.

“You’ll see these horse barns every once in awhile,” says Elyo. “When Knob Hill was annexed into the city, they made horses illegal. But you could keep your horse until it died, or you sold it; you just couldn’t get another one. And so there are several horse barns still around.”

As Platte Avenue became a major transit path, it also became a dividing line.

“Platte Avenue is actually a local highway,” says Elyo. “It’s people’s primary east-west connection for Colorado Springs. It divides the neighborhood in half. It’s also a dividing line for the council district. South of Platte is one City Councilor, and north of Platte is another City Councilor.”

This man-made division, Elyo says, is exactly why the group aims to bring symbiosis to the neighborhood through art.

What’s more, Elyo says, the community has been neglected when it comes to public amenities like safe pedestrian crossings.

“We call ourselves the Knob Hill Urban Arts District because it’s a very urban area. There’s lots of traffic. There’s a lot of furniture stores, pawn shops, and used car dealerships,” Elyo says. “And I feel like it’s just really been forgotten. There’s not really a public school, there are no parks, and there’s no grocery store. It’s also really difficult to cross Platte if you’re a pedestrian. So we want to try to highlight those issues, and maybe help offer suggestions on how to repair them.”

Murals can bring attention to community issues, Rieger says, like the Harvest Goddess, a mural by Molly McClure on the side of Platte Furniture.

“We did the Harvest Goddess to draw attention to the food desert that is here in Colorado Springs,” Rieger says. The wall was painted with a grant from the Colorado Department of Health and Environment in partnership with Colorado Springs Food Rescue.

In Knob Hill, Rieger says, many buildings are derelict and empty; used for storage, or not used at all.

“We’ve even approached developers to come in and renovate the buildings, and rent them out,” he says. “So we’re not just about murals. We want to help invigorate things on the business side. We want to bring in galleries, coffee shops, and other businesses.”

The support and partnership of local businesses has been integral, Rieger says, especially from mainstays Platte Furniture and Ace Pawn. In addition to offering their walls for art, these businesses have allowed the collective to use the outside space between buildings for a variety of community-run events, like a recent Black Lives Create Fest that welcomed artisans from the region to sell goods and promote services.

One unique benefit of Knob Hill is its prevalence of owner-occupied businesses, Rieger says. "We don’t have to go through corporations and different layers of bureaucracy to get permission to paint.”

To create a mural, Elyo says, an ideal wall is first identified.

"Then we figure out who owns it," he says. "We talk with the business owner. We figure out how big the piece wants to be, and put a budget to that. We’re self-funded. Then we solicit for artists. We never know what we might get permission to do, or what the building owner might want to request.”

“Sometimes the owner wants a certain subject,” says Elyo. “Like with our Fannie Mae Duncan mural. We wanted to do a Fannie Mae mural to celebrate her life, and the owner happened to have gone to her legendary Colorado Springs jazz club, the Cotton Club, when he was a young man. And he was so excited to have Fannie on his building.”

“The public looks at this, and they are just endeared by a business who allows this,” says Rieger.

The collective is also responsible for painting an impromptu rainbow crosswalk in celebration of Pride that garnered the attention of local media and celebratory citizens before being painted over by the City “within 13 hours,” Rieger says.

Unbeknownst to Rieger, Pride Fest had been petitioning the City to install a permanent rainbow crosswalk.

“I believe that controversy helped Pride to get their temporary crosswalk installed," says Rieger. "It was a healthy form of artistic expression.”

The raw talent of local graffiti artists, muralists, and painters has increased foot traffic, welcomed new visitors to snap photos, and contributed to a community feel in the otherwise disjointed throughway.

"The response has been very positive," Elyo says. "Even the furniture stores are seeing more foot traffic. We’re seeing people take their senior pictures and organization photos in front of the murals. And overall, I do feel like it’s inspired more murals in the city.”

“We still have pushback. We still have people saying it’s all graffiti. But I don’t think that graffiti really exists. It’s all art to me,” says Rieger.

“Art historians 200 years from now will call this the street art era,” Rieger says. “So let’s take advantage of it, and do it while we can. Because when I was younger, this wasn’t allowed.”

Now, the excitement is palpable.

“Every time I see a blank wall, I’m like, ‘I wonder who owns that building,’” says Rieger.

His goal?

“I want to paint every building on the block."