Rural district’s Teacher of the Year uplifts funding for public education

SAN LUIS, Colo. — “Bye! Have a good summer!” educator Helen Seay called on the last day of school, waving across her high school English classroom at exiting students.

Seay, 30, teaches ninth through 12th grade English and digital arts at Centennial School District R-1 in San Luis. One of Colorado’s oldest towns, San Luis is home to around 600 residents. Around 200 students from the southern half of Costilla County attend pre-kindergarten through grade 12 here.

“It's a really unique opportunity,” Seay said of working at a small school in a small town. “I love getting to know the students and the community really well, getting to have all my students for four years, and being able to really build that relationship with them.” Seay acknowledges it’s a privilege. “Just seeing them grow up is very cool. Not everybody gets to do that,” she said.

“Class with Ms. Seay is fun. We learn so many new things,” said 10th grader Johnny Perea. “I think Ms. Seay is one of the best teachers here. She’s always coming in with a positive attitude. No matter what kind of a day it is, she has a smile on her face.”

Chosen by fellow teachers and staff as Centennial’s Teacher of the Year, Seay went on to receive a nomination for San Luis Valley Educator of the Year. At a ceremony held mid-May, Seay and other amazing Teachers of the Year from around the San Luis Valley gathered to enjoy a night honoring their hard work.

“I just feel very grateful and very humbled, and very proud to be part of Centennial,” Seay said.

“Ms. Seay is a smart and fun teacher to be with,” said José Molina, a 10th grader who took digital arts. “She earned her nomination.”

While there is a lot of opportunity to get to know and work with students on a personal level, “at the same time — and I know it's true of all schools — but it feels particularly like at a rural school, everyone has to wear about 50 different hats,” Seay said. “And I don't even think I'm exaggerating.”

With a staff of around 20, “just being able to provide more opportunities for students like clubs and extracurricular activities” can be difficult, she acknowledged.

“It can be hard to do all of those things for students on top of the normal day of teaching many classes,” she said. “My grading load is not as big because I don't have, you know, up to 200 students, as many as a big school. But the prep work is more because my colleagues and I teach five, six, seven different classes a day, depending on who they are and what subject area.”

Rural schools are also affected when it comes to funding, Seay said.

Helen Seay is Centennial School Teacher of the Year for San Luis and was a nominee for San Luis Valley Educator of the Year.

“I know that legislators are working on trying to increase school funding, but it really does impact smaller schools, especially because we don't have as big of a student count,” she explained.

According to the Colorado Legislative Council Staff, the nonpartisan research staff of the Colorado General Assembly, school district funds are typically raised through a combination of state and local measures, including sales tax, property tax, and individual income taxes. According to a 2020-2021 report, per pupil funding in Colorado ranged from $8,056 in the Academy School District in El Paso County to $18,446 in the Agate School District in east central Colorado.

“Per pupil funding is highest in rural districts due primarily to the enrollment size factor adjustment in the school finance formula, and lowest in districts that qualify for little additional funding from the size, cost-of-living, or at-risk adjustment factors,” the study explains.

Centennial District R-1, the southern portion of Costilla County, receives between $12,000 and $15,000 per student.

Seay said Colorado’s Budget Stabilization Factor, a legislative effort enacted in 2010 that reduces total funding proportionately across districts based on demands of the state’s budget deficit, also lowers public education funding. According to the Colorado General Assembly, this legislation has reduced funding in this district by around $1,000 per pupil per year — over $200,000 in lost funding annually in Centennial’s case.

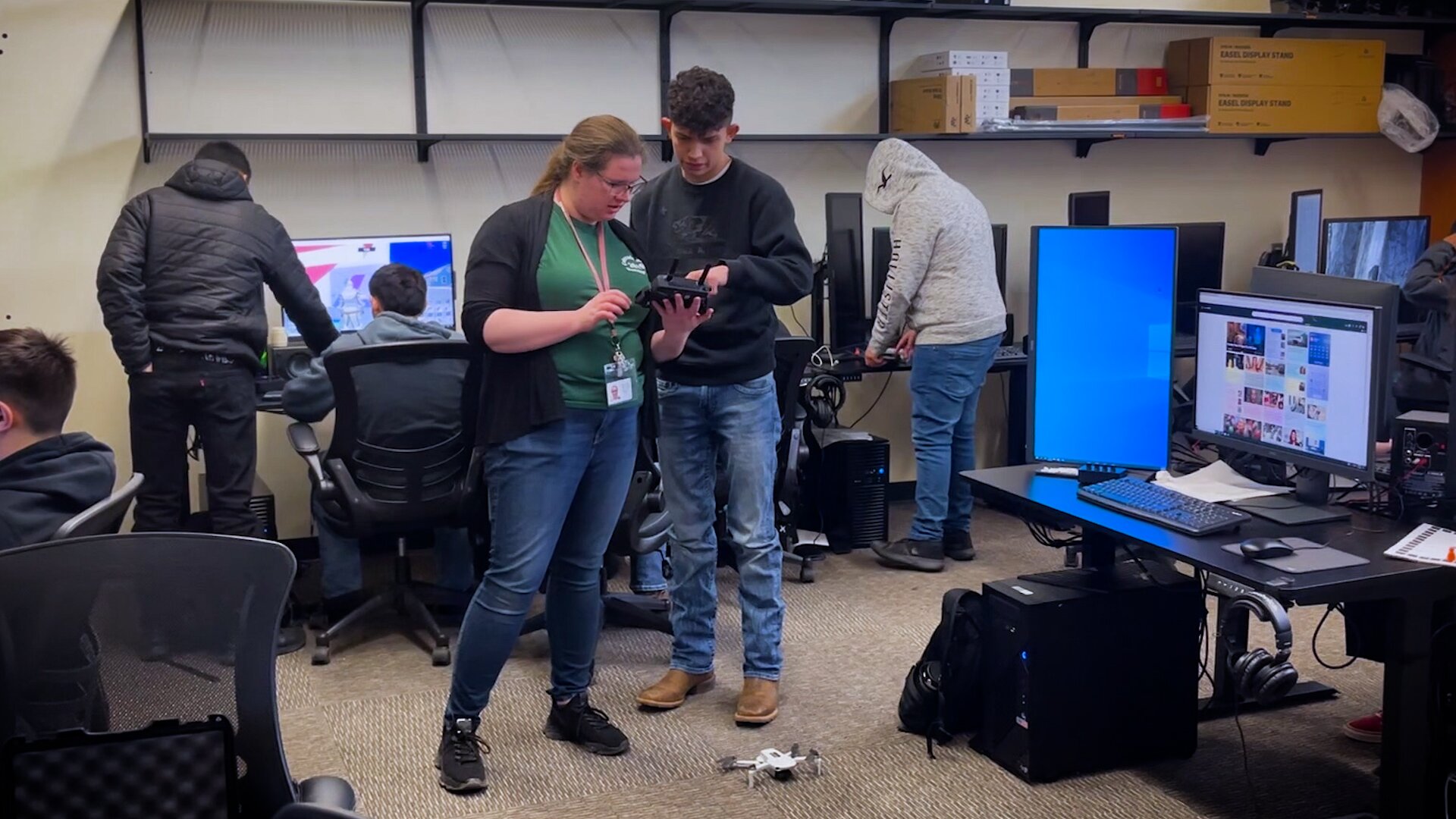

Helen Seay in her Digital Arts classroom at Centennial School in San Luis.

“The Budget Stabilization Factor is a fund that Colorado has had for the past 13 or 14 years,” Seay explained. “It was created at the time of the recession. The state began to set aside extra money, and one of the places that they cut back on is education. A lot of the money that could be going towards education has instead been diverted into the budget stabilization fund.”

Seay said the fund has “grown over the years to the point where a senior in the class of 2022 had never experienced a fully-funded education in their K-12 career, which I think is very sad. Increasing school funding would be amazing. We would be able to hire more staff and mental health professionals to better meet the needs of students.”

Across the state and the nation, teacher resignations and a shortage of teachers continue to impact education offerings and educator-to-student ratios.

Wrapping her fifth year of teaching in San Luis, Seay says it’s even harder for rural schools to recruit and retain educators and staff. Like other districts around the state, Centennial has welcomed teachers from the Philippines on work visas to supplement their staff.

Multitasking is the hallmark of educators, Seay said, but wearing many hats takes on a new meaning in a rural area. Here, teachers often instruct multiple courses that may span grade levels.

“If we can't fund a full staff position, then it becomes a combined role to where one person is doing two or three different jobs. Yes, it's possible to multitask. Yes, that's part of being in a school. But it does make it harder,” she said.

[Related: A tale of two trends: School districts grapple with teacher shortage, student enrollment]

San Luis, Colorado. Population: 613.

“I do think it can be harder for rural schools to recruit people, and to hire teachers and have them stay,” Seay continued. “A lot of educators wouldn't necessarily come to a rural area because the pay is lower in a rural area versus in Denver. Granted, the cost of living is lower, but at the same time, with inflation, it doesn't necessarily feel that way anymore. The teacher's salary is not keeping up with inflation — no salary is.”

[Related: Living paycheck to paycheck, Fruita teacher struggles in cutthroat housing market]

Lack of public education support and funding over decades have refocused curriculums and dwindled test scores, while billions of dollars in deficit affect the almost 200 public school districts across Colorado. For residents of the state’s 39 rural school districts — serving around 73% of the state’s land mass — the strain is significant, Seay said. Still, the state maintains that more than 90% of its school districts meet Colorado’s benchmarks for fiscal health.

As a teacher, it can feel like “the work is never done,” Seay said, but finding ways to connect with students brings joy and remains a priority. Seay said she loves “finding ways to be creative and try new things, work with students, and to help young people grow.”

Kate Perdoni is Interim Co-Director of Journalism at Rocky Mountain PBS and can be reached at kateperdoni@rmpbs.org.