For 80 years, the kids of Silverton have sold rocks. A documentary follows their 'rock star' journey

SILVERTON, Colo. — David Dibble’s escape from Los Angeles included hopping a train.

After attending film school and working as a filmmaker in southern California, Dibble wanted to “be a kid again,” so he decided to return to an attraction he visited as a child: the Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad (D&SNGRR).

Completed in the summer of 1882, the D&SNGRR is “one of the last vestiges of the development of the vast resources of the west through the advent of a working rail system,” according to the National Register of Historic Places.

The town of Silverton was officially established in 1874, only eight years before the railway was completed, though settlers looking for gold had populated the area as early as 1860. Historically, the Ute tribe controlled the land, but ceded the area in the 1873 Brunot Agreement.

The railroad was the main source of transportation for the people of Silverton in the years predating highway expansion through the Rocky Mountain region, and it was also the primary method for transporting ore from the mines of the San Juan Mountains. The line became an attraction for passengers after it was featured in Hollywood Westerns of the 40s and 50s. In 1961, the railway became a federally-designated National Historic Landmark.

Now functioning as a tourist attraction — the town’s last major mine closed in 1991 — the D&SNGRR draws hundreds of thousands of riders each year, according to History Colorado and the Colorado Encyclopedia.

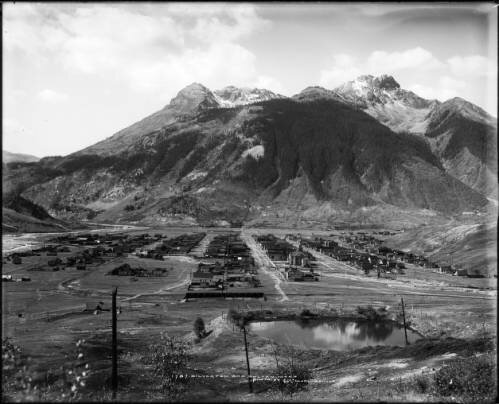

A 1911 photo shows the bird’s eye view of Silverton, Colorado. The narrow gauge track is visible in the foreground.

Photo: Louis Charles McClure, via Denver Public Library

Dibble joined the railroad, first as a brakeman and eventually becoming a conductor, not with the intention of making a film about life on the tracks. After all, he specializes in narrative film. But Dibble could not help but notice the children of Silverton who sell rocks, ores and gems to the train’s passengers, a tradition that dates back to the 1940s when the minerals were actually coming from the mines. These entrepreneurial kids — “rock stars,” as Dibble calls them — would become the subjects of Dibble’s documentary, “Rocks 4 Sale!”

Rocky Mountain PBS spoke with Dibble over Zoom about his film, which airs on Rocky Mountain PBS Thursday, Dec. 28 at 7:30 p.m. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Rocky Mountain PBS: Where did you get the idea for your film “Rocks 4 Sale?”

David Dibble: I was living in L.A., and I wanted an escape from L.A., so I decided I would move to Durango to work on the railroad.

This is something I rode as a kid, so I decided I just wanted to kind of be a kid again. An escape from L.A. for just a summer. It ended up being quite a long time. So I was working for the railroad as a brakeman and eventually a conductor. So every day, you would see the kids out there selling rocks. And so that's how I was introduced to them.

In fact, I always tell a story now how one little girl would actually run from her little wagon up to me when the train arrived and punch me in the stomach and then run back. And I thought, “I don't think I like this Silverton place.” But once I learned that there were some other coworkers on the railroad that used to sell rocks — they grew up in Silverton and their parents used to do it and their parents used to do it — and then I learned that there was the city ordinance that kind of dictated you had to stop at age 13. So, I realized there was a lot more to it than just cute little kids selling rocks. And so that's when I got interested. I thought I might tell their story.

RMPBS: I was telling my coworkers about the film and I said, “It's about kids selling rocks.” When you say that out loud it sounds pretty Dickensian, but what's the origin of the kid selling rocks?

DD: As it kind of says in the movie, kids in Silverton were always, apparently — I guess the word is industrious — trying to sell stuff, trying to make it and really you can credit Hollywood for kind of discovering the train and Silverton and making that really popular.

And so the train really got a lot of business in the late 40s and 50s — tons of tourists there — and so you had all these people and that's where they kind of got the idea, “Let's sell something to the tourists.” And it kind of came from the mining tradition, too, where fathers would bring home gems in their lunch boxes from the mines for their kids to sell.

So it started in the late forties, fifties and became a tradition, obviously. And nowadays or those same are the rocks that the kids are selling.

RMPBS: Nowadays, are the rocks the kids are selling still coming from the mines?

DD: No [chuckles]. I would say some have good stuff. Others just find it in tailing piles, others find it by the river. Some find it right there near the train, some find it other places.

It's not as good as back [in the 40s and 50s], but some of [the kids] go to a lot of trouble. They will go and find their own rocks, will break their own rocks and they call that mining. But overall, I would just call them “just rocks,” although they're crystals, they’re galena, pyrite, so forth. But it's not coming directly from the mines anymore.

RMPBS: What was it like working with kids for the film?

DD: That was the best part of it, actually, because I would just go and basically hang out and spend a few hours with kids. I started doing that once I got permission from the parents and so forth. I glued googly eyes on my microphone and I would say, “Hey, I'm making a documentary about you guys.” And all the kids are obviously used to strangers and very open. So suddenly they just kind of opened up after a few minutes and you just hang out with kids being kids, being silly, being clever. So I actually enjoyed that part a lot. I enjoyed going back up to Silverton to film the kids.

Although the rocks no longer come directly from the mine, the children of Silverton still sell stones, gems and other minerals from the surrounding areas.

Photo: David Dibble

RMPBS: What do you hope that people will take away from the film after they watch it?

DD: Well, it's been traveling to film festivals for two years now, and I'm loving hearing the laughing in the audiences. They find it funny and charming, but it opens up a little bit of history, so you learn a little bit about the history.

But ultimately when I was working as a conductor and [the kids] were kind of disappointed in tourists, how many of them just passed them by on their way to go get their hamburgers or whatever, and kind of ignored them. I think if more people knew about them, everybody would be buying rocks.

And I love that it's going to be shown on Rocky Mountain PBS, so this Colorado story will be shown through more of Colorado. I love that part.

RMPBS: Were you on the lookout for stories when you were working on the train, or did it just so happen that you noticed the rock sellers and thought it would be a good film?

DD: It just happened. There it was. And normally I don't make documentaries at all. I'm normally a narrative filmmaker. And so here was this story of kids, right in front of me. It's kind of peer pressure, too. Other friends that said. “You should make a documentary! You should make a documentary!” To which I thought, “No, no, I shouldn't.” But eventually I gave in and I started the project. But the story kind of just fell in my lap, literally. And every story I’ve made in Colorado is just like — there's just so many possibilities there, so the stories just kind of up here.

RMPBS: What is something that you learned about Silverton that surprised you or that you didn't already know in the process of making this film or visiting the town?

DD: I would say characters. It's a small town. And so it kind of makes itself have more characters, just to live there. But in the process of making this and becoming part of the community — because I was on the train, but I also played trombone, so I would travel there pretty much every weekend and join their their brass band — and by doing that, I became a little more part of that community and knowing more people and making this project.

It's just a lot of very neat, interesting people up there. That was my favorite part of going to Silverton … Silverton is just full of characters.

Kyle Cooke is the digital media manager at Rocky Mountain PBS. Kylecooke@rmpbs.org.