After a stroke, painter Randy Pijoan explores new ways of creating

PUEBLO, Colo. — It’s the little things.

“Before this happened, I was able to walk and hug people. I could pick up things with my left hand, and canoe. I could set up my easel — I could set up anybody’s easel,” said artist Randy Pijoan. “But a blood clot thought otherwise.”

After suffering a stroke in June of 2016, Pijoan lost connection with the left side of his body. He now uses a wheelchair.

“The freedom in choosing a color, or choosing a sky for a piece, is what I miss,” reflects Pijoan. “Just the freedom of knowing what hot gravel feels like under my feet, next to a river, with the hot air blowing.”

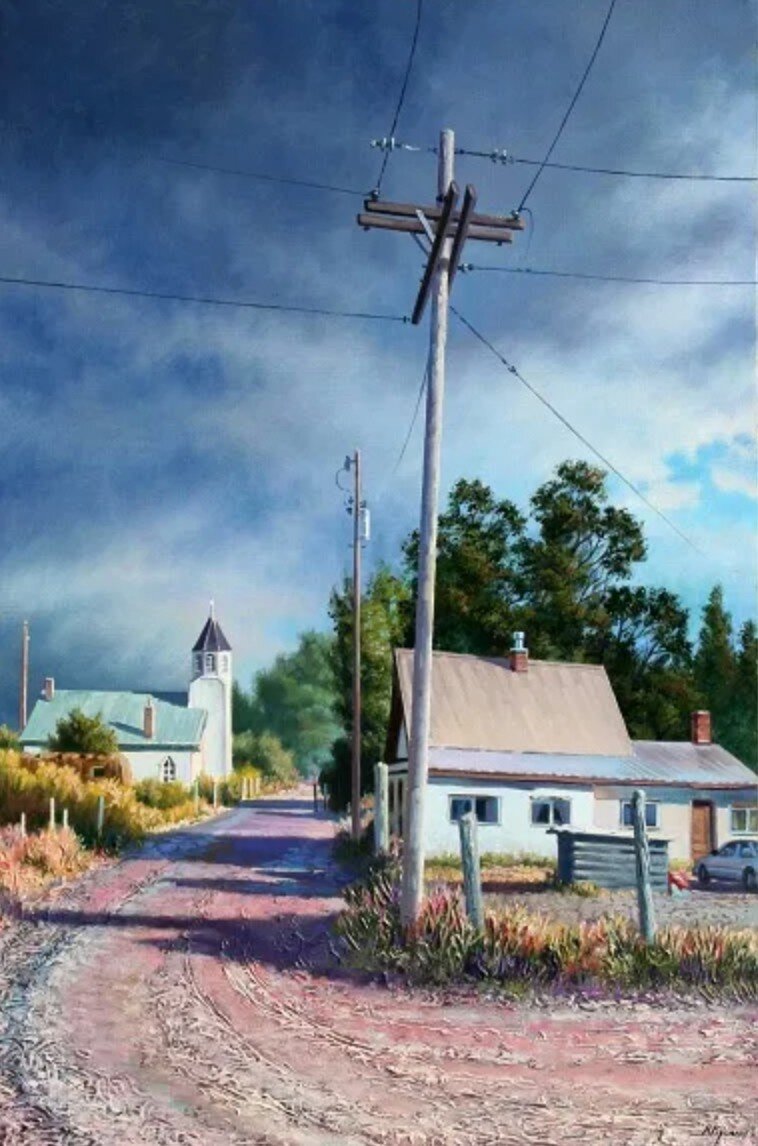

Pijoan primarily painted with oils, creating hyper-realistic landscapes and figurative works. He is now exploring new ways of making art, including visually expressing his own health issues — such as painting his migraine headaches.

“What I’m painting now is what I am understanding, as I’m understanding it,” explained Pijoan. “I’m trying to create a dialogue with myself, and with others — to help others understand. I want them to ask me what the paintings are about, so I can tell them, ‘Last week I had a seizure that looked just like this to me.’”

This summer at the Sangre de Cristo Arts Center in Pueblo, a retrospective of Pijoan’s work reflects his years living and working in Northern New Mexico and the San Luis Valley. In addition to his personal painting practice and studio, Pijoan ran a community arts space and coffee shop on Main Street of San Luis for years, providing local youth with art instruction and supplies.

“I always told my art students, ‘You have to become a trained observer first, before you become a painter.’ Even if you play the blues guitar, or write poetry, the observation has to be correct first. Those senses have to be functioning. I thank God I had all that before the stoke — and that I had my hand to paint it,” said Pijoan.

Titled “Where the Pavement Ends,” Pijoan said this show reflects a new path.

“This evening, on my way here, the sidewalk from the hotel to the arts center literally ended at a certain point,” Pijoan said. “As someone who relies on a wheelchair to get around, I view the world very differently now.”

In the exhibit, Pijoan showcases works highlighting the landscape and communities of the Sangre de Cristo mountain range of Southern Colorado.

“There’s also a lot of New Mexico, because I was born in Santa Fe,” said Pijoan. “My family is from the Upper Rio Grande of Northern New Mexico. I can’t get that out of my blood. There’s just too much magic; too much in the ether.”

Pijoan lives with his wife in the Pacific Northwest, maintaining close ties with his “chosen family” in the Southwest, he said, who helped him through some of his hardest times, including recovering from a near-death experience and open-heart surgery in 2013.

“This stroke has needed a lot of support to keep me from drowning just in the darkness of it,” he said. “We think we’re going to live forever, and we’re doing just fine — until it happens.”

He urged people to reach out to those who may be going through a hard time, visibly or invisibly.

“I look back at my youth now, and wish I had been more present for those who were suffering,” he said. “If you know anybody who is paralyzed or in a wheelchair, or if you know anybody who has lost the use of a limb, or has epilepsy, or any of the horrors that come with that, please pray for them. See how you can help. It’s a challenge for the family, and for people like myself. It’s just not easy.”

He relates his own process of rehabilitation to the healing effects that art has on greater society.

“Whether a sculpture on a street corner or a mural on the side of an old building, art [has] to be there to heal society, one little atomic particle at a time,” Pijoan said.

“It’s what my brain is also going through, trying to heal all these neuron connections from the stroke,” he continued. “It takes a long time, but with these baby steps, we’ll get there as a society, I believe. And it’s going to be wroth it. As Plato says — It’ll be beautiful, and it will be true, and it will be good.”

The exhibit, closing August 30, is part of a group of exhibitions currently on display at the Sangre de Cristo Arts Center.

Kate Perdoni is a multimedia journalist with Rocky Mountain PBS who can be reached at katepedoni@rmpbs.org or via Instagram at @kateyslvls.