Quadriplegic man rediscovers his love for guitar by creating the 'Quadricaster'

FRUITA, Colo. — "My fall was just nothing," said Jay Wells, reflecting on the split-second motorcycle crash that robbed him of his two biggest passions: riding motorcycles and playing guitar.

It wasn't a slow-motion, action movie crash. Wells was simply riding behind another man who misjudged the trail, and instead of running into the man, Wells veered right. Wells landed perfectly wrong and found himself unable to move.

"When they say quadriplegia, that's a scary word. It means all four," Well said, referring to all four limbs of the human body. After his crash, he was paralyzed from the neck down, with limited mobility.

More importantly, Wells believes he never would have spent the kind of time he spent with his daughters if there was never an accident.

Responding to people who might show sympathy for what Wells lost, he often replies, "Sure, there's a list of things I can't do. But guess what I can do? And, I do them."

Cullen Purser is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach him at cullenpurser@rmpbs.org.

A lifelong passion for music

Around age 12, Wells would sneak out with his dad's 1956 Fender Telecaster electric guitar. He was left-handed, but his dad wasn't. In order to play, Wells had to hold the guitar upside-down, which made playing chords difficult. This led Wells to a style of playing that was more single-note and atmospheric.

“My buddy Frank and I played all the time, and we had good equipment. So we ended up playing at places because we sounded good,” says Wells.

Wells’ style of playing provided a perfect compliment to Frank’s rhythm guitar. Audiences enjoyed listening to the duo. Frank would lead with rhythm and chord, and Wells loved creating the nuanced sounds in the background. He always had dreams of being a studio session musician.

The day everything changed

Wells' grandfather sat him down on a motorcycle for the first time when he was 6 years old. His grandpa set the throttle, and let Wells loose. The skills we pick up as children make them second nature when we are older, and so the motorcycle became an extension of Wells' body. While never a pro rider, Wells took the sport seriously and participated in many competitions over the years

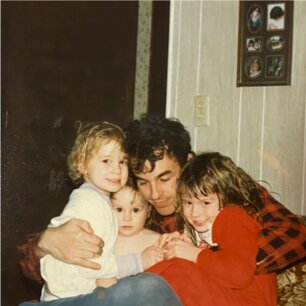

When his daughters were young, he sat them down on motorcycles, just as his grandfather had done for him. It was a gift of joy and freedom. Why not share that with his girls?

In 1992, Wells was a young father. His three daughters were all under the age of 10. He was set to move to Oregon with plans of buying a motorcycle shop and teaching at a college in Eugene. One evening, he went out for a ride in the rolling shale hills at the base of the Book Cliffs like he’d done countless times before. He and another rider were heading back when the rider in front of him missed a turn and laid his bike over. Wells’ split-second decision to veer away from the other rider caused him to fall off his bike.

"I just hit wrong. I hit the top of my head instead of the side," Wells recalled.

He never lost consciousness. He was present for the whole thing. He just had the feeling that he couldn't move his body.

The doctor was a straight shooter, Wells said. "The doctor came in and told my family, ‘He's paralyzed from the neck down, get used to it.’ And so, what do you do from there?"

Wells' immediate thoughts upon hearing this had nothing to do with motorcycles or guitars. His number one concern was if he would he ever get to hug his girls again.

A legacy continues

Wells has what is known as incomplete quadriplegia. Complete quadriplegia is what most people think of when they hear the term: complete paralysis of all four limbs. That was Wells' initial diagnosis. However, exactly four months to the day after the accident, he moved his left leg ever so slightly. Shortly after that, he moved his left thumb.

Those small movements started a long journey of recovery that would ultimately plateau with a relatively strong left side of his body, and a weak and under-responsive right side. His right hand would never be able to press string to fingerboard and play notes on a guitar. He thought little of it. He could hug his girls. He felt fortunate he could still work as a researcher and technical writer and provide for his family.

Fifteen years later, Wells' brother had a Les Paul guitar and placed it in Wells' lap and said, "Play it or drop it." Wells struggled to hold on, but he didn't drop it.

“And then I realized when I grabbed the neck I naturally put my palm up and I found myself moving my fingers a little. All of a sudden you think, maybe I can do this.”

He strummed with his left hand, and to his genuine astonishment notes rang out. His love for guitar was reawakened. He started to look through catalogs for a guitar that would rest on his body so that he could play. But, he couldn't find anything. Wells decided to make one.

He based the shape on a Fender Stratocaster and called his creation the Quadricaster (his sense of humor wasn't affected by his injury).

Wells bought a blank wooden electric guitar body and started sculpting it so it could rest on his lap. He carved a big scoop on the upper part to make clearance for his right arm to rest on so that he could more easily reach the strings. He wired it to his preferred specs and installed the best pickups. The guitar is outfitted it all with electronics that assisted in creating long, sustained notes. He started making music again, the kind he always loved: nuance, atmosphere, complimentary sounds.

Reflecting on the motorcycle accident, Wells said, "I am sort of glad it happened to me. Because if not, I would have owned a bike shop in Oregon and my girls would have been racing and riding because they all loved it. And no doubt, they would have gotten hurt.”