Nizhoni Elizabeth Smocks on what it means to be Afro-Indigenous

DENVER — Nizhoni Elizabeth Smocks has never felt like she fit in.

“I’ve never felt Native enough or Black enough, so I’ve always found my place with the outcasts,” Smocks said, who identifies as Afro-Indigenous. “Still, to this day, I feel this way.”

Smocks, whose first name means beautiful in Navajo, described being Afro-Indigenous as, “Being both tied to the earth and being part of the earth.”

While she is proud of her culturally rich, ethnic background—Smocks is of the Coyote Pass and Deer Spring clans as well as African American—her journey to self-acceptance hasn’t always been easy.

“I think it’s a very beautiful and unique position to be in and I didn’t appreciate it until later in life,” she told Rocky Mountain PBS.

Smocks grew up in Chinle, Arizona on the Navajo reservation near the Canyon de Chelly. As a child, she enjoyed playing outside—from cliff diving, horseback riding, and swimming to herding and sheering sheep.

“I had fun as a child,” she said. “I am thankful because growing up on the reservation allowed me to sit outside with my family and watch the satellites drift by in the night sky.”

Although Smocks has fond memories of her childhood, her family endured racism from fellow Indigenous people, “Because of the way we looked, because we were Black,” she said.

“Some of my grandma’s family were shocked when they found out my grandmother married a Black man. They would say harmful and hurtful things to her like, ‘You are going to have polka dot children.’”

While living on the reservation, Smocks' family—including her extended family—resided in a four-bedroom, government-issued home.

“It was very crowded,” Smocks said. “But we were also very fortunate because we had running water, we had electricity.” Today, Smocks said there are still people in her family that don’t have running water.

While living on the reservation, Smocks attended school where Navajo culture classes were regularly taught. She and her classmates attended class daily at the hogan (spiritual homes) and read coyote stories, which are tales and literature written by Indigenous people.

However, when she was growing up, most of Smocks’ teachers were white. For Smocks, this became a challenge because some of the teachers' disconnect from genuinely understanding the Navajo culture.

“I felt that many of my Caucasian teachers wanted us to behave in a certain way and did not honor many of our traditions,” she explained.

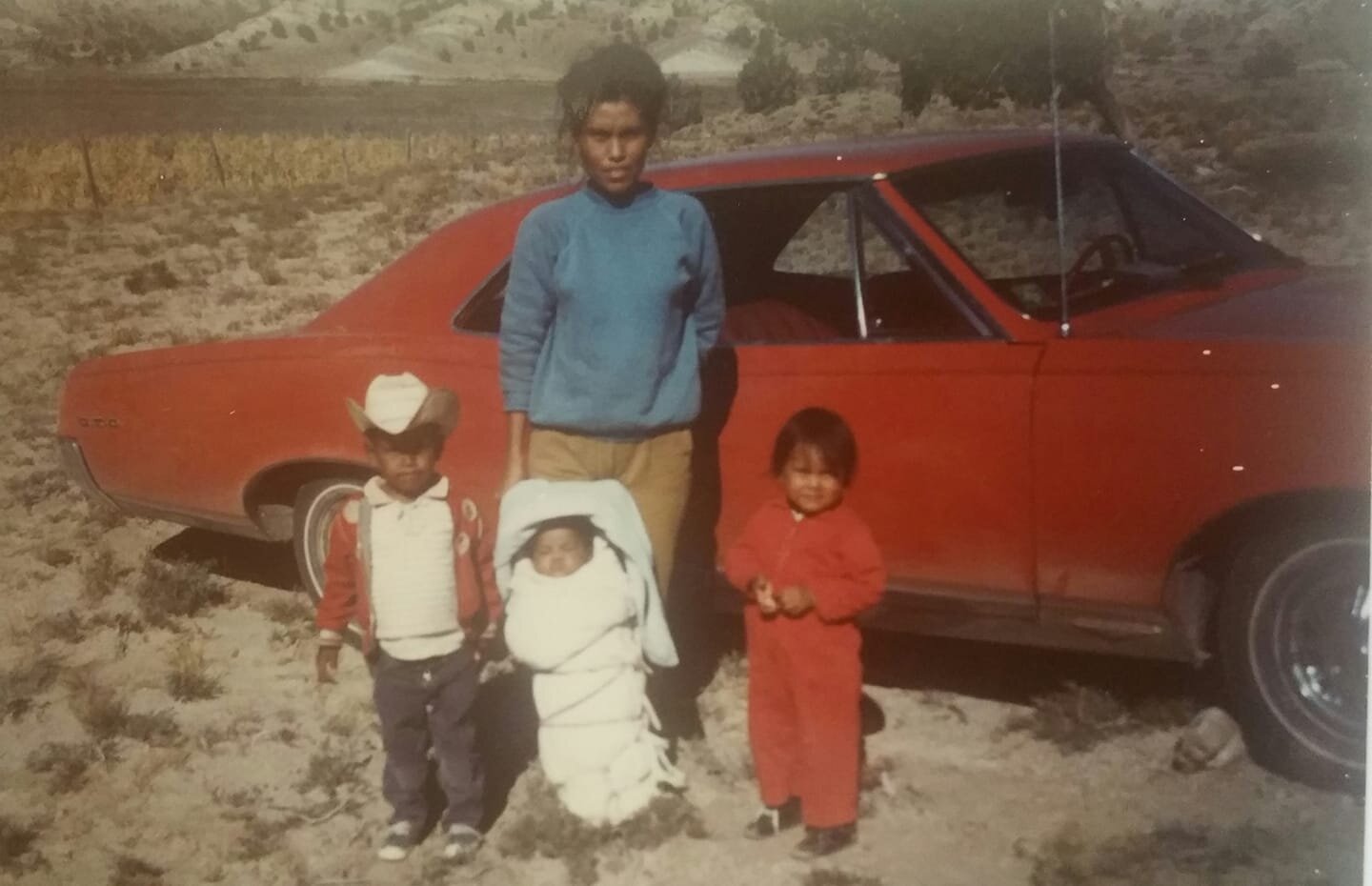

Smocks shared her grandmother, Elizabeth Lisa James, who has since passed away, meant the world to her and her family.

“My grandmother raised me. She was the glue that held the family together,” Smocks said. “My mother had me very young.”

After her grandmother’s passing in August of last year, Smocks was given a family heirloom, her grandmother’s necklace, which Smocks refers to as the “family diamonds.” She also received her grandma’s rings, blankets, and more.

For Smocks, her grandmother taught the family about the importance of community and to live with the intention of loving others. For example, James worked in human resources and helped bring a grocery store to their reservation.

“The Navajo Nation is one of the largest federally recognized tribes in the U.S. My reservation is roughly 27,000 square miles. There is probably on a few more than ten grocery stores within the reservation,” Smocks said.

Now residing in Denver, Smocks shared that she is all too familiar with bizarre and stereotypical notions about her Indigenous heritage. According to her, these myths make it difficult for Indigenous people to stand up and have a voice of their own.

“Not all Native American tribes have reservations or casinos,” she said. “Another misconception is that we should be happy with the land we were given, but the reality is that we didn’t choose the land. In most cases, Indigenous people are given the most undesirable land that the white folks did not want.”

Smocks added that sometimes she has a tough time meeting and connecting with people because they immediately assume that because she’s Indigenous, she must have a problem with alcohol, “which is another ignorant and racist misconception,” she said.

For Smock, calendar holidays like Indigenous Peoples’ Day and Native American Heritage Month, are just a start to helping people understand Native culture.

“I would rather see other things done to help Natives,” she said. “I would like it for tribes to be able to get access to people who can help them reclaim their land or tribes receiving financial support to be able to provide scholarships to encourage the importance of education.”

She added: “As with all things, any positive acknowledgment is appreciated. We need to however, think bigger and collaboratively on how to bring the community into the experience. In most cities, there is only one Indigenous Peoples’ center with limited resources, so programming does not reach the entire population. Ultimately, we need to be honest and forthright in teaching the history of our nation and having those uncomfortable conversations to generate change.”

Smocks, who is partially fluent in the Navajo language, said learning her native tongue was particularly important for her because she still has family members who don’t speak English.

Additionally, Smocks recalled one of the Navajo legends she heard when she was young: “Once the children stop speaking the language, the world will end.”

Smocks recited an important Navajo prayer for Rocky Mountain PBS called “Walk in Beauty,” which says to “live your life with integrity, love, light, and faith in everything that you do,” she said.

Smocks hopes that other Afro-Indigenous people feel seen and heard.

“You are important,” she said. “Your ancestors survived so much so you could succeed.”

Lindsey Ford is a multimedia journalist for Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at lindseyford@rmpbs.org.