Last night at Nimo’s

FORT COLLINS, Colo. — Chef Hiroshi Nimota stands at the sink in the kitchen of Nimo’s Sushi. He guides a slender, wooden-handled chef’s knife along his whetstone. Nimota began his career as a sushi chef 50 years ago. Tonight is his last night.

Nimota inspects the blade with his fingers.

“It’s done,” he said. “This knife is for fish. I bought it in 1985.”

The knife is a fraction of its original size, but has served Nimota well for much of his career, which dates back more than half a century.

Despite the financial challenges restaurant owners face in 2024, from higher costs to more reserved customer spending, Nimota’s decision to close was personal.

“The restaurant business is always tough because of long hours. I worked 70, 80 hours a week. Go home at 11, sometimes midnight,” he said.

At five o’clock, an army of Nimota’s beloved customers streamed through the door. They greeted him with retirement cards, balloons and shots of sake.

Dave Hansen, a longtime fan, said that Nimo’s was the only place in Fort Collins he goes for sushi. “The quality of the fish, the owners — it feels like home,” he said.

As the orders rolled in, Nimota’s son, Takashi — who began working at the restaurant when he was 14 — quelled the rush.

“It’s bittersweet,” he said. “I’m sad that it’s closing but happy for my parents since they’ve worked so hard.”

Nimota sharpens and inspects his knives before his final dinner service.

Photo: Cormac McCrimmon, Rocky Mountain PBS

Nimota learned how to make sushi in Tokyo, where he grew up. He met the owner of a sushi restaurant in 1974 and started his training.

“I’m not a really, really smart guy,” he said. “I didn’t go to college. After high school, I started working.”

Nimota often wanted to quit.

“Especially in the 1970s. It was a hard time. If I made a mistake, well, sometimes I got a big knuckle right here,” he said, pointing to his cheek where he was slapped. “A lot of people quit.”

Initially, Nimota’s true passion was music. He saw the Beatles perform in Tokyo in 1966. Following the show, Nimota picked up guitar and began performing a solo act at local night clubs once or twice a week. Nimota crossed paths with a musician named B.T. Collins from southern Oregon, who suggested they play together.

“He was a fantastic harmonica player,” said Nimota.

A year later, Collins returned to the United States.

“He kind of invited me to come with him. I was so interested. I quit my job and came to the United States.”

Nimota seasons a dish at the sushi bar. He prides himself on the quality and simplicity of his ingredients.

Photo: Cormac McCrimmon, Rocky Mountain PBS

Nimota arrived in the U.S. in 1978. He crashed at his friend’s house, then moved to San Francisco, where he met a restaurant owner from New Orleans in need of a sushi chef. Nimota packed his bags and headed to the bayou. After a short stint in New Orleans, he returned to Japan to await his green card.

There, he met his wife, Noriko, who has helped to run the restaurant from the beginning.

The couple returned to the U.S. in 1982.

“New Orleans is a good place, but I wanted to see somewhere else,” he said.

Nimota took a job in Denver and in 1992 saw a listing for a sushi business for sale in Fort Collins, near Colorado State University.

“It was the perfect size,” said Nimota.

He wanted more control over the sushi he made and the fish he bought.

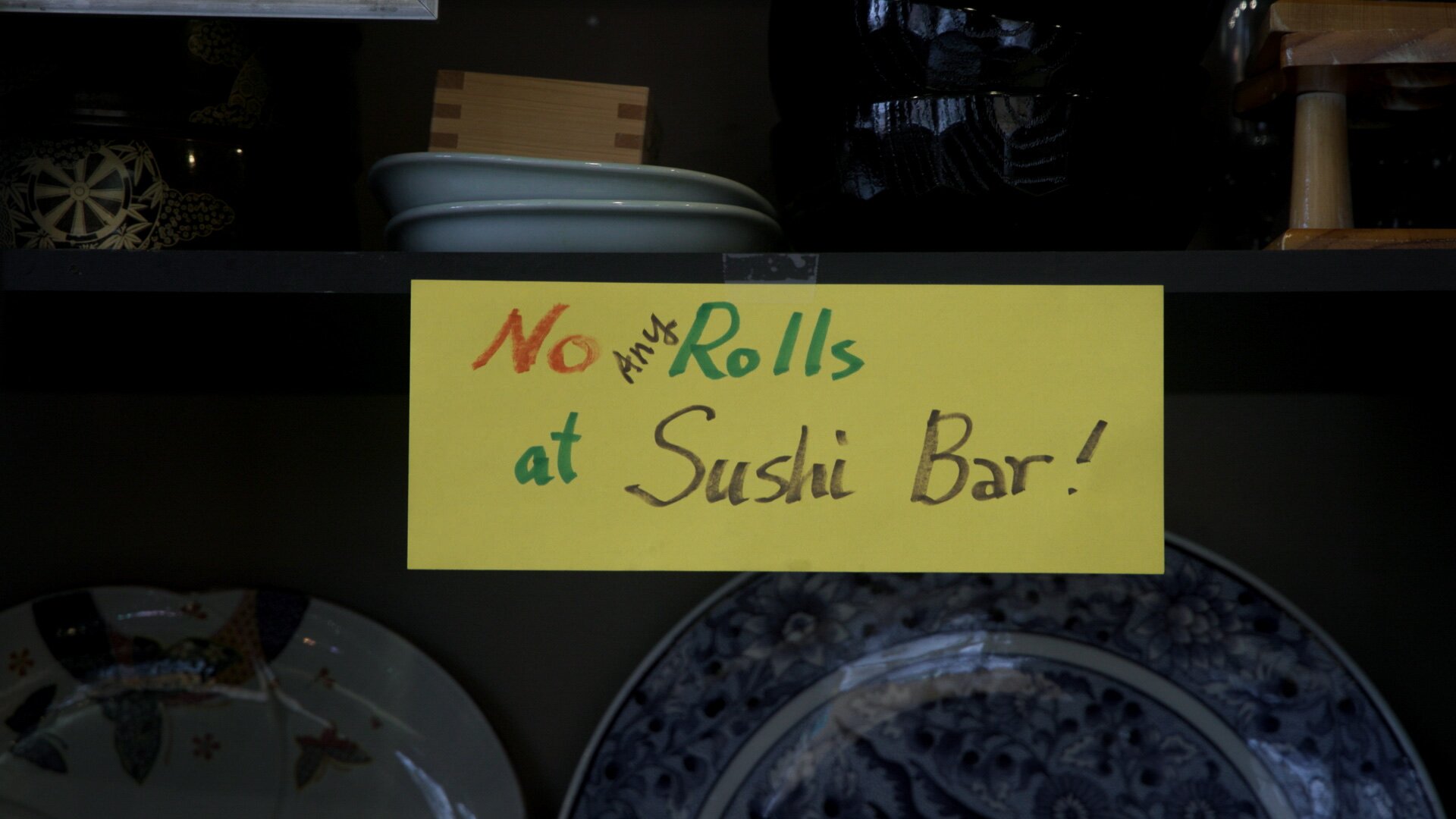

To this day, Nimota derides what he sees as a bastardization of sushi. A sign behind the counter reads, “No Rolls at Sushi Bar!”

Nimota prefers to serve traditional Japanese style sushi with fish and rice only, instead of complicated rolls.

Photo: Cormac McCrimmon, Rocky Mountain PBS.

Nimota learned to make rolls to please customers, but he prefers the simplicity of traditional Japanese sushi made from rice and fish only. He believes that the zany rolls some restaurants sell allow them to mask the lower quality fish they use.

“We have to make money because it’s a business, but my focus was never on profit,” said Nimota. “I never doubt customers keep coming back [sic].”

According to Nimota’s website, his restaurant was the only Japanese-owned sushi restaurant in Fort Collins. Across Colorado, asian-owned businesses make up 3.8% of small businesses in the state, according to data from the American Business Survey.

Nimota’s son, Takashi, sears a piece of fish.

Photo: Cormac McCrimmon, Rocky Mountain PBS

As he’s aged, the side effects of his work have become more acute. Nimota suffers from arthritis in his fingers. Yet through it all, he’s remained optimistic about his work.

“Some days, tired or hungover, you know, oh, gosh, I really don't want to go to work,” he said with a chuckle. “But I want to see everyone every day. Different people in front of the bar. I make my sushi by hand directly to the customer. That’s a really, really fun job.”

Nimota prepares a fresh batch of rice. He says that rice is the most important part of quality sushi.

Photo: Cormac McCrimmon, Rocky Mountain PBS

Although he’ll miss his customers, Nimota is eager to have more time for himself.

“I’m 75. My life expectancy is 88, 85, so 10 more years,” he reasons.

He plans to return to Tokyo more regularly to spend time with his siblings and old friends.

The rest of the time, he looks forward to playing golf, fly-fishing and taking his camper to Wyoming.

“We usually would go up two or three nights per year,” said Nimota. “Now we can spend a whole week or the whole season.”

Cormac McCrimmon is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. Cormacmccrimmon@rmpbs.org