Measuring indoor air quality helps to calm nerves as in-person learning returns

DENVER — Our snowy and wet spring may be top-of-mind now, but the destructive wildfires of last summer are a close memory, and their impact on air quality was far-reaching.

Many Coloradans who suffer from asthma (or other lung sensitivities) were breathing the results — more fine particulate matter — measured in (PM2.5) levels.

“2.5 microns - that's the actual size of the particulate [found in the air] and we know that the finer particulates get deeper in the lungs and have longer health impacts and more severe health impacts,” said Denver Department of Public Health and Environment air quality program manager, Michael Ogletree.

By taking a closer look at school-wide statistics Denver, Ogletree identified what he called a pressing need concerning children’s health.

“In our case we looked at asthma rates at public schools and we found that we had a higher than national average of asthma in our Denver Public School kids,” he added, explaining that particulate matter can come from things like car exhaust, industry emissions, wildfires, and construction.

Innovation competition via Bloomberg Philanthropies inspired DDPHE to apply for grant

Ogletree and his peers within the DDPHE imagined a way to improve air quality by installing air pollution sensors around schools. The sensors would provide real-time data, educating and inspiring students to utilize easy-to-implement tools and campaigns for reducing air pollution: things like creating idle-free zones for cars and encouraging walking and biking to school.

In 2018, DDPHE applied for and won a $100,000 initial grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies to launch the idea. Then came a $1,000,000 US Mayors Challenge grant to get the "Love My Air Denver" program up and running. Its goal? To address high asthma rates in Denver’s youngest generation.

“We tried to figure out how are we going to solve this problem or work towards solving that problem,” he adds.

That’s when the team reached out to local schools, many located near highways and industrial areas with higher pollution levels.

“We really wanted to have an equity focus on that, so looking at asthma rates as well as free and reduced lunch rates as an economic indicator to make sure that we had an equitable distribution in our school partnering program,” said Ogletree.

In the past two years, the "Love My Air" team built this program from concept to reality while engaging with the community throughout the process.

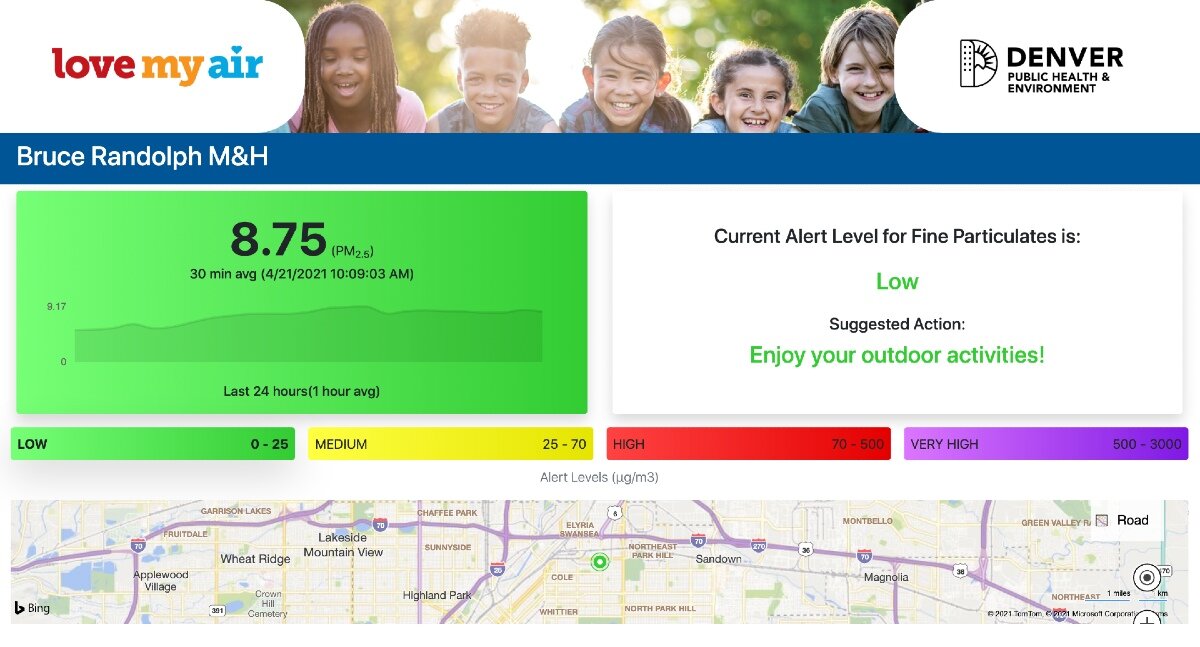

“We developed the sensor with a local aerospace engineering company,” said Ogletree, adding that parents were key in designing a useful online dashboard to display results in real-time.

To date, 20 schools are part of the program. They have plans to double that number by the end of the year.

Each school receives an air monitoring sensor to be placed in a location where students regularly interact with it — places like playgrounds and school entranceways. Schools also receive resources from Ogletree and the "Love My Air" team, including the interactive dashboard and teaching tools to engage the community.

Education around the meters and what the results mean are the first step.

Then, schools can take it from there.

“We have tools to implement an anti-idling [of cars] campaign but some schools may want to take it to the next level and do an art contest where the kids could design anti-idling campaigns and then we can get those printed and then put those up at those schools,” Ogletree said.

There is a menu of options that allow for flexibility within each school and the surrounding neighborhood.

Pandemic focused need to examine indoor air – north Denver school leads the way

Bruce Randolph School in north Denver is located near Interstate 70 and the congested Central 70 Project currently underway. Traffic and industry can create high levels of pollution for this community.

That’s why school principal, Melissa Boyd, was excited to be one of the first to join the Love My Air Denver project. She also saw this as a way to promote the deeper mission of the 6-12 grade school.

“Bruce Randolph School is a very special place. We are named after Daddy Bruce Randolph who was a local restauranteur and philanthropist,” said Boyd.

Look around the hallways and the B.R.U.C.E. (Brilliance. Respect. Dignity. Character. Efforts.) values are infused into the school’s atmosphere.

“As we think about like what Daddy Bruce Randolph did for his community, he was all about giving back,” Boyd adds while discussing the importance of addressing neighborhood needs. “We're really looking to what we can do as a school to give back more.”

The entire school was part of the pilot program – administration, the school nurse, teachers and students. One teacher felt a need to take it to the next level.

“My passion for science is infectious diseases. My background is in immunology and infectious disease. That was what I studied in college,” said 11th grade science teacher Sarah Peterson.

Peterson recalls being intrigued by the power of science from an early age. While preparing for her next unit class, she stumbled upon an old high school lab book. In it, the message she highlighted from a favorite teacher during a lesson about the pandemic of 1918: “Pandemics. We are living on borrowed time.”

The message was eerily prescient. Peterson’s upcoming scientific research course needed to adapt. It would address the pandemic head on. She’d been reading research pointing to COVID-19 being transmitted by airborne particles more often than by surface touch.

“What I realized is that our kids were scared, and their families were scared because everyone was. And part of the way to counter that fear is just to think about, what do we know? What do we not know? And where does our power lie,” said Peterson. “How can our knowledge help keep us, our staff and our families as safe as possible?”

Measuring a virus in the air is difficult. Tracking CO2 helps

“You cannot measure virus particles in the air very easily so instead what you can do is measure carbon dioxide levels, because the virus particles can enter the air through speaking, laughing, singing, coughing — things like that. And that's also how carbon dioxide gets into the air because we exhale carbon dioxide,” she considered, while connecting with Ogletree.

The "Love My Air" team shared handheld CO2 monitors and Peterson’s class of 30 juniors got busy testing the indoor air flow in more than 20 classrooms throughout the school. There was good news.

Most days, the strong air flow from opening windows, doors and a robust ventilation system were working. On the CO2 meter, Peterson taught students to recognize safe levels typically between 400-800ppm for indoor spaces.

“What we found is that our building is phenomenal and that most days our levels were between, like, 480 and 600 because we have very strong airflow,” she added.

As students and teachers started returning to in-person classes, they shared this data in hopes of calming apprehensions.

“If we can track the likelihood of aerosol transmission in our school and if we can lower those potential rates, then that could have a lot of power in both students feeling good about coming back and then teachers feeling okay that they're safe to be here and teach,” said Peterson.

Hands-on learning from this class is helping students understand science and assess data for accuracy.

Rebecca Romero is a junior at Bruce Randolph School. She is one of Peterson's students.

“For me as a student, safety is my number one priority. Learning is my second priority. I'm trying to keep everyone in my family, and my friends and the staff here [at school] safe,” she said while discussing her passion for science and her plans to attend college to continue that learning.

Her classmate, Wilson Guzman, feels lucky that their teacher decided to provide this class.

“It’s not just about coronavirus that's affecting us. There's much more in the air than we know, and it could be dangerous to a certain point. Having ventilation — it’s saving lives,” he explained. “I want to be safe and try not infect my family or myself and to not endanger anyone else. [Learning about CO2 in class] made it more reassuring for me to come back to class.”

Peterson and her class are connecting with other Denver Public Schools, offering help to monitor their indoor air quality and share simple tips to improve that flow.

“We can add air filters to individual rooms. We can create strategic airflow through opening windows and doors,” she adds, highlighting low-cost ways to improve indoor air quality.

What’s next for 'Love My Air Denver?' Nationwide outreach and a phone app for all

With education and community engagement leading the way, Ogletree and the "Love My Air" team are building a program that municipalities and schools across the country can replicate. A partnership with the University of Colorado Boulder is helping them study the accuracy of the low-cost sensor measurements.

The Bloomberg Philanthropies grant funds will stretch through 2022. Ogletree is confident the programs will continue long after that.

“The real cool part is — the curriculum is something that will be able to continue and be to hub around all of the mitigation strategies,” he added, highlighting the benefit of sharing the collection of data from DPS schools. It will ensure future schools are set-up for success.

“They'll have data to support their request for change.”

This summer, "Love My Air" will be releasing a free smartphone app, allowing anyone to access the network of data and resources, sparking ongoing conversations of air and health safety.