55 years after leading the Kitayama strike, Lupe Briseño reflects on ‘what we women can do'

For more stories about the labor movement in northern Colorado, watch "Colorado Experience: Cultivating Change."

BRIGHTON, Colo. — Dr. King is slain in Memphis. Kennedy is dead, victim of assasin. Police, protesters clash in an atmosphere of hatred. Black power advocates ousted from Olympics.

These are just a few of the headlines from The Washington Post and The New York Times over the course of 1968, one of the most consequential years in American History. And while the stories behind those headlines are defining moments in our nation’s struggle for civil rights, one of the stories that did not make the front page was a critical point in the story of Colorado — and the country.

Page 58 of the Oct. 20, 1968 Sunday edition of The New York Times includes a near-full-page advertisement for the bygone luxury department store B. Altman and Company. Squeezed into the left-hand side of the page next to a description of Miss Bergen's Moisture Blend makeup, which claimed to “highlight your good features and fade-out your flaws,” was an article from John Kifner. The headline reads “FLOWER WORKERS PERSIST IN STRIKE.”

Kifner was reporting from Brighton, Colorado, on the Kitayama flower plant, where a group of predominantly Mexican-American women was leading a strike against the miserable working conditions at the plant.

Rachel Sandoval was one of the five women who organized the strike, along with Guadalupe “Lupe” Briseño, Martha De Real, Mary Sailas and Mary Padilla. In a recent interview with Rocky Mountain PBS, Sandoval said that the news of assassinations and civil unrest in places like Memphis or Chicago was not on her mind as she picketed while pregnant outside of Ray Kitayama’s nursery.

“We just did what we had to do and that was it,” Sandoval said matter-of-factly.

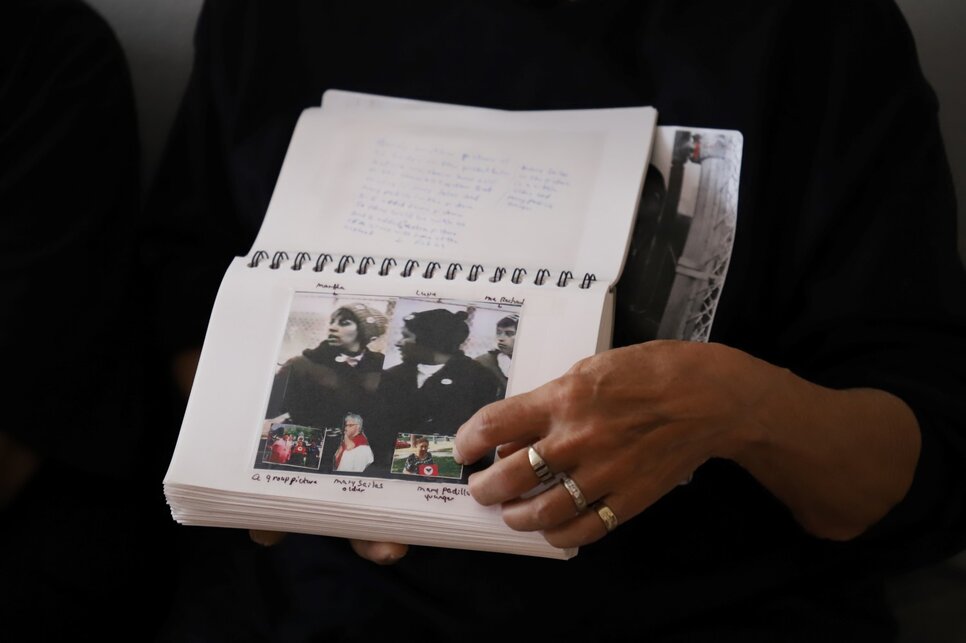

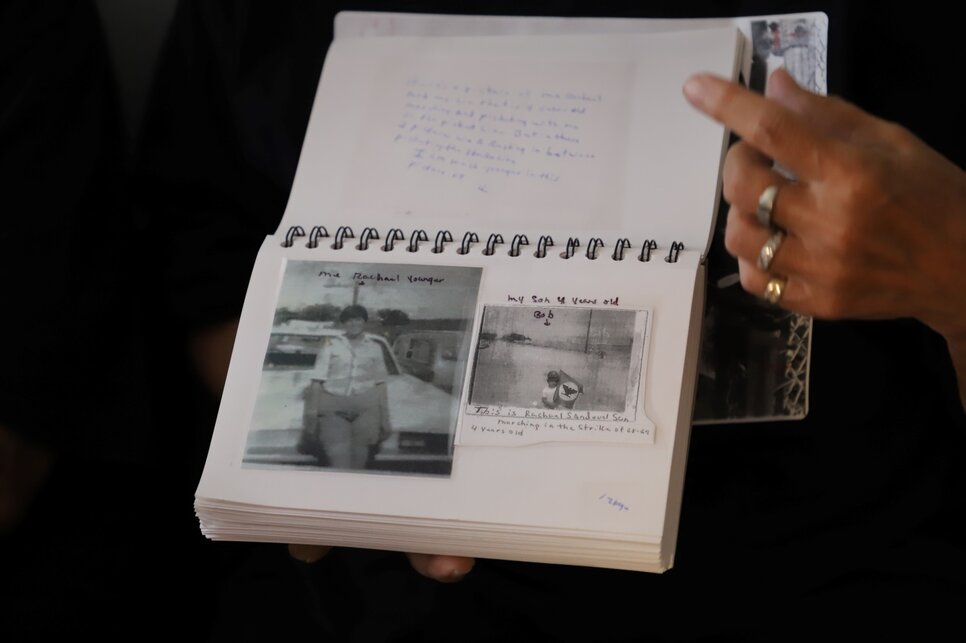

During the interview, Sandoval and Briseño sat in Briseño’s living room wearing matching shirts. The black t-shirts featured the names of the five main organizers and a photo of Weld County police officers breaking up their strike. Sandoval flipped through a photo album that chronicled life on the picket line.

In a way, Sandoval downplayed the impact of the 221-day strike that captured the attention of Cesar Chavez and became a key moment in El Movimiento, the Chicano Movement. Rocky Mountain PBS met with Briseño and Sandoval at Briseño’s home in Brighton, more than 55 years after the two women led the strike. Briseño, 90, is in hospice care but recounts her days on the picket line as though they occurred earlier this year, not more than half a century ago.

“It's something that you never thought could happen,” Briseño said of the strike. “But it did. And instead of the women getting weak, they got strong.”

How the strike came to be

Briseño’s children were not old enough to go to school when the family first moved to Colorado from Texas, so she stayed home with them. When the kids eventually started school, Briseño found work at the Kitayama Flower plant where she worked on the nursery floor cutting flowers and making carnations.

From the beginning, Briseño realized how poorly the management treated the majority-female staff. Sandoval and Briseño recalled the plant’s owner, Ray Kitayama, calling the women “pigs.”

“The way that they treated [the women], spoke to them, I couldn't tolerate,” Briseño said of management.

The physical conditions were just as bad. The women worked unprotected from the insecticide that soaked the flowers. Water leaked from the roof and, combined with the water used for irrigating the carnations, the greenhouse’s dirt floor turned to mud, leading to frequent accidents and creating a “muggy” environment.

“You'd get bronchitis because of the humidity,” Briseño explained. “And you’d have to go see the doctor and they [the managers] would tell you, ‘You cannot see the doctor. You go, you lose your job.’”

Briseño decided that these conditions had to change. With her colleagues, she formed the National Floral Workers Organization (NFWO) and held meetings about the plant’s working environment. At the very first meeting at the community center in Brighton, Ray Kitayama was one of the first people through the door.

“And he said, ‘Everybody go home’ like we were small children,” Briseño recalled. “He said, 'Go home, watch television. If you don't like what's going on on television, go to sleep. See you tomorrow morning.’”

The next day at work, police officers were stationed throughout the plant. It was then that Briseño began talking to her colleagues about unionization. Kitayama caught wind of these conversations and, on a Saturday, drove to Briseño’s house and fired her.

“I said, ‘this is nothing,’” Briseño recounted. “‘I will fight you, win or lose, but I will fight you to the end.’”

Briseño went to the Capitol in Denver to find out what kind of rights she had to form a union. She was disappointed to learn that the employees at the Kitayama plant were technically considered farmworkers, and as such, Kitayama did not have to recognize their union if they formed one. Asked by the Times in October of 1968 if he would recognize the NFWO union if it won a vote from the workers, Kitayama reportedly grinned and replied “heck, no… we’re 100% within the law. Anyway, I think they [the workers] have about shot their wad.”

Life on the picket line

The NFWO strike began July 1, 1968. Made up of about 60 people, the NWFO was more than half of the Kitayama workforce. The picketers marched outside of the plant for 221 days. People took notice.

Priscilla Falcon, a Chicana/o and Latinx Studies professor at the University of Northern Colorado, described the support Briseño and the NFWO received was “amazing.”

“And it was across-the-board support,” Falcon said. “You had SDS from Boulder, you had the United Mexican American Students, you had the Colorado Council of Churches, you had the Teamsters, you had the National Teachers Federation.” Cesar Chavez, the labor leader and civil rights activist who co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) with Dolores Huerta, supported Briseño and the rest of the workers.

However broad the support for the striking women was, it wasn’t universal and it didn’t always last, Falcon explained.

“The community became divided,” Falcon explained. “[Briseño’s] husband suffered a series of beatings. Her children were bullied at school because of the strike … And it became very dangerous for Lupe. She talked about how Kitayama employees harassed her.’”

Falcon said that Briseño is one of her heroes.

“To have her and these women decide that they are going to have a union, that they're going to stand up, that they're going to change things was something that was unheard of,” Falcon said.

As the strike went on, the number of picketers declined. Falcon said that by January of 1969, only about three or four people would be on the picket line at one time. Some picketers returned to work at the Kitayama plant because they needed the wages (about $1/hour). Others found work in nearby sugar beet fields and would join the Kitayama strike before and after their shifts. But Briseño and Sandoval — who was pregnant — stayed strong.

“You'll be surprised what we women can do when we make up our mind,” Briseño said.

In February of 1969, after learning that the National Labor Relations Board officially denied the NFWO’s petition to form a union, Briseño, Sandoval and the other leaders of the strike decided on one last act of civil disobedience: chaining themselves to the gate of the Kitayama plant.

“They met secretly the week before February 15, and they decided that they were going to chain themselves to the fence so that the employees could see them when they walked into the plant,” Falcon said. “So that week, Lupe and her colleagues went to a lumber yard and they bought a logging chain and then they bought a lock.”

Early in the morning of February 15, 1969, Briseño, Sandoval and the other strike leaders locked themselves to the Kitayama gate. They didn’t even tell their families about the plan.

Weld County police officers were called to the scene, where they cut the chain and sprayed tear gas on the women at the direction of Ray Kitayama.

“We couldn't see nothing. We couldn't do nothing because we were so foggy and all gassed up,” said Sandoval, who was pregnant with her daughter as the officers gassed her. “We were coughing and choking and covering our mouths.”

That was the day the strike ended.

The aftermath

The workers never achieved unionization, but Briseño said the workers at the flower plant reported improved conditions after the strike ended. Wages increased, as did the allowance of bathroom and water breaks for workers. Briseño did not reap the benefits of her work on the picket line, but the women who worked at the plant did, and that was a victory in and of itself.

“It's just part of life,” Briseño said. “We have to speak up and protect each other.”

Although Briseño and Sandoval didn’t necessarily think of their strike as part of a nationwide movement, their organizing efforts were undeniably notable in the widespread fight for improved working conditions on America’s farms in the 1960s. For example, while Briseño and Sandoval were on the picket line in Brighton, Chavez’s National Farm Workers Association was in the middle of its years-long strike against California’s grape growers. Just a few years prior, activists like Ernesto Galarza worked to end the Bracero Program, which growers abused as a way to keep farmworkers’ wages low and thwart unionization efforts.

Nevertheless, unionization remained out of reach for Colorado’s farmworkers for more than 50 years after the Kitayama strike. It wasn’t until 2021 when democratic Governor Jared Polis signed the “farmworker bill of rights” that farmworkers in Colorado earned the right to join a union.

The Kitayama plant exploded in 1978. A feeder pipe in the boiler room broke, filling the room with combustible material. A photo from The Denver Post archives shows the sprawling nursery reduced to ruins and covered in ice after fire crews worked more than eight hours in sub-zero temperatures putting out the flames.

Ray Kitayama, who was incarcerated at the Manzanar Internment camp in California as a young man, continued to have a successful career, the eight-month strike and explosion notwithstanding. Kitayama Brothers, Inc. was once the largest flower business in the United States. In 2007 Kitayama passed away at age 83 according to his obituary in the East Bay Times, which made no mention of the strike. Kitayama Brothers is still in business.

Briseño, who was inducted into the Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame in 2020, knows that she, too, is leaving behind a memorable legacy. A wall in her living room is filled with family photos, and a glass case proudly displays family heirlooms and awards, like the Cesar Chavez Leadership Hall of Fame trophy she received from the Denver Public Library after her induction three years ago. Mostly, though, Briseño is proud of the lessons she taught her family.

“I don't feel sorry for what I did,” Briseño said of leading the strike. “My husband and my boys support me all the way. My family is very proud and are teaching the new generation that we shouldn't tolerate anything like that.”

Kyle Cooke is the digital media manager at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach him at kylecooke@rmpbs.org.