Update: As of February 17, 2022, Denver residents can order naloxone and fentanyl-testing strips through this order form from the Denver Department of Public Health & Environment. The order form is part of an effort from Substance Misuse Program to make the overdose-reversing drug more widely available.

In November of last year, Rocky Mountain PBS reported on the dire need for Narcan in the city. Denver's Harm Reduction Action Center (HRAC), for example, struggled to secure enough Narcan as the city’s overdose crisis worsened.

You can read that original report below.

DENVER — It only takes a few seconds to administer naloxone, but those moments can be life-saving.

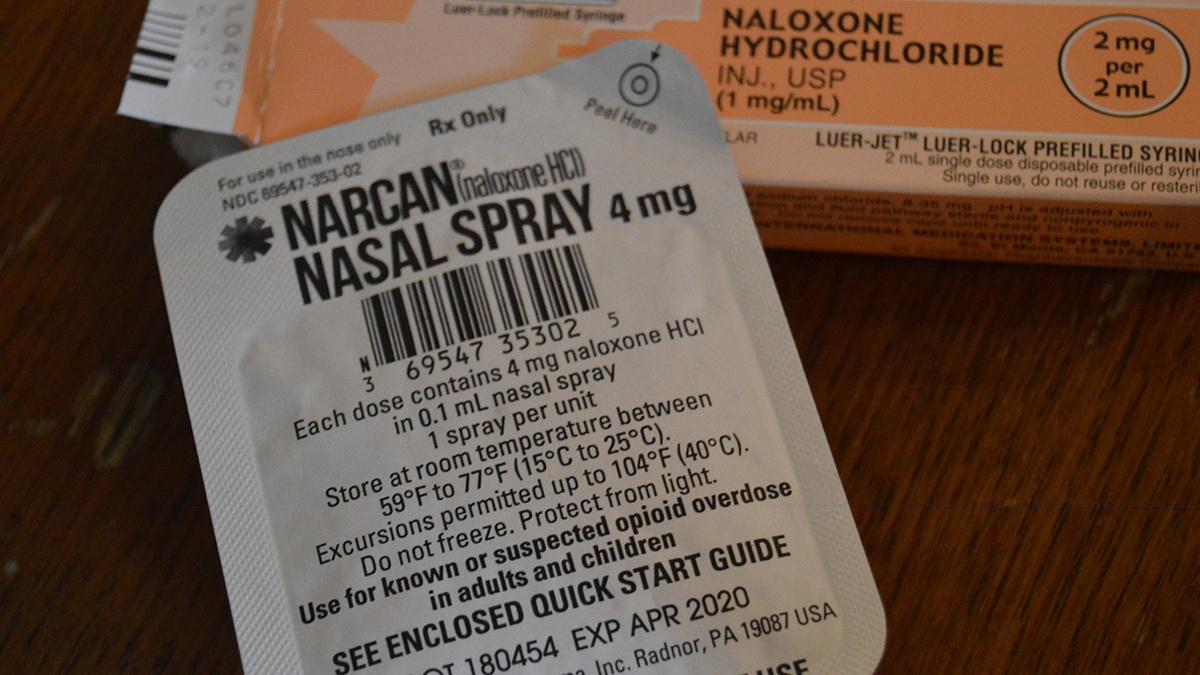

In most scenarios, a spray of Narcan—the nasal version of the drug naloxone—in each nostril can be the difference between life and death. When used correctly, the medication can block certain receptors that opioids bind to and reverse an overdose.

Right now, the need for Narcan is more critical than ever. Over the last few years, an uptick in drug overdose has killed thousands of Coloradans. According to data from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE), from 2018 to 2020 a staggering 864 Coloradans died from fentanyl-related overdoses since the synthetic opioid took a deadly hold on Colorado’s illegal drug market.

So far in 2021, at least 525 Coloradans have died from fentanyl poisoning, more than five times the death toll in 2018 when illicit fentanyl first appeared in the state.

“In 2019, the numbers were terrible. 2020, they are even worse, and we expect we’ll exceed the number of overdose deaths in 2021 in Colorado,” said Dr. Hermione Hurley, who works in Denver Health’s infectious disease clinic and substance-use clinic. Hurley regularly sees people with opioid dependency and substance use disorder.

According to experts, many people who die from overdose don’t even know they have ingested fentanyl.

“Fentanyl looks innocuous. It looks like a little blue pill these days,” Hurley said. “But it actually can be a completely different potency, completely different surprising contents to people.”

Unlike heroin, illicit fentanyl is completely synthetic, making it extremely cheap to produce and easier to sell. State officials say they are seeing the drug trafficked into Colorado from Mexico, where it is manufactured from chemicals made in China. Often disguised as oxycodone and heroin (and mixed with other substances), the drug is 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times more potent than morphine. According to the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), just two milligrams of fentanyl can be potentially lethal.

“People literally don't know what they're using or how they're getting it,” Hurley explained. “Things that are being sold on the street made to look like oxycodone are all fentanyl, some Tylenol, some antihistamine, whatever people can find. What people are getting is completely different from what they used to get, [it's] much more potent and much more variable.”

And overdose doesn’t discriminate, Hurley said. More people are dying younger and overall life expectancy is going down.

“This is an epidemic of overdose, wrapped in a pandemic of a COVID-19. And it's overlaid on decades of racial and social inequity,” Hurley added.

To make matters worse, Narcan is difficult to come by this year. As executive director of the Harm Reduction Action Center (HRAC) in Denver, Lisa Raville has struggled to secure enough Narcan as the city’s overdose crisis worsens. HRAC, the state’s largest health agency for people who inject drugs (PWID), provides fentanyl testing strips, syringe disposal, hygiene products, food, vein care, and typically, access to Narcan.

“We are in the worst overdose crisis we've ever seen in the United States, Colorado, and in Denver,” Raville told Rocky Mountain PBS. “There is a lot of grief happening among people who use drugs among service providers, because people we know, love, and serve are dying of preventable overdoses and it doesn't have to be so.”

While HRAC has had access to naloxone since 2013, the need for larger quantities exacerbated in 2021, almost a year into the pandemic.

Prior to 2021, the organization received the opiate antagonists through the Naloxone Bulk Purchase Fund. Born from Senate Bill 19-227, the fund allows qualifying entities like HRAC to purchase naloxone or Narcan at low or no cost. HRAC is one of at least 25 entities in Denver that receives the life-saving medication from the fund.

But the record-high overdose rates across the state are outpacing the fund and the CDPHE has struggled to keep up with order requests. At the beginning of the fiscal year, $1.7 million was allocated for the Naloxone Bulk Purchase Fund; and by October 2021, the CDPHE processed $466,310 in orders (about 26 percent of the available funding). However, according to Andres Guerrero, manager of CDPHE's overdose prevention, the high demand for naloxone is outstripping the funds.

“The Naloxone Bulk Purchase Fund has not had a consistent source of funding since it was created, and funding through state and federal sources has varied. Colorado has seen an increase in overdose deaths in the last year and demand for naloxone has increased significantly due to the introduction of fentanyl into the Colorado drug supply,” Guerrero told Rocky Mountain PBS.

As a result, Raville spent at least $29,000 of grant money originally intended for other HRAC programs to supplement the overwhelming need for Narcan, which costs about $75 a kit. She even made a call out on Twitter to reveal HRAC’s depleted naloxone supply and encourage community members to donate to HRAC so Raville could purchase more Narcan.

“[CDPHE] just doesn't seem to have enough money. So every time I'm asking them...they're limiting it,” Raville said. “As a frontline service provider, it is not fine. So it's not so much of a shortage of product but that I'm not consistently getting it through the Naloxone Bulk Purchase Fund.”

Typically, HRAC gives out about 300 Narcan/naloxone kits per month, totaling roughly 3,600 per year.

In 2020, the organization conducted 719 naloxone reversals; 67 percent of those were administered outside in alleys, parks, and bathrooms. So far this year, the organization has reversed 759 overdoses—the most ever.

"The last time, I was the rescue breather," Raville said. "Every time I closed my eyes for the next week, I saw his face."

According to Raville, CDPHE fell behind in filling naloxone orders during the second quarter of this fiscal year. When more funds became available this past August, CDPHE had to fill all the back orders before addressing the immediate demand. And when the money started to come in, Raville said, it was still inconsistent.

Consistent supply is key for HRAC as many of the people it supports are unhoused. In mid-October, Raville accepted expired Narcan donations from “colleagues across the country” to help them get by. Luckily, HRAC started receiving weekly naloxone orders in the beginning of November after inconsistent and delayed requests from the Naloxone Bulk Purchase Fund.

In the coming weeks, Raville is hopeful more funding will become available as the overdose death toll is destined to increase. Currently, money for the Naloxone Bulk Purchase Fund is sourced from federal COVID-19 stimulus funds via the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) and the State Opioid Response Grant. According to CDPHE, the need for funding for naloxone has come up in conversations among the Behavioral Health Transformational Task Force, which is chaired by State Sen. Brittany Pettersen (D-Lakewood).

“We have a proposal of around $10 million with ARPA funds to go in for this year and next year for additional funding because of the increased need,” Senator Pettersen told Rocky Mountain PBS. “This is a priority for us. It's unfortunate that we underestimated the need out there because we did prioritize, you know, making sure that we had significant funding for Narcan or naloxone and because of the need out there, they've already run out.”

The Behavioral Health Transformational Task Force created the proposal during the interim committee process so they could “increase buying power to get the most for our tax dollars by pushing it together,” Pettersen explained. Additionally, there is another proposal to make sure emergency department doctors have access to Narcan. The task force will present the report when the General Assembly reconvenes in January.

Until more funds are approved, HRAC is accepting monetary donations, as well as items from their Amazon wish list, and encouraging people to carry Narcan on them. It can be purchased at most pharmacies.

While stigma towards drug use and fear of retribution may hinder PWID from acquiring it themselves, Hurley believes everyone should carry the life-saving medicine.

“Colorado is grateful and lucky to have an open prescription. So we've been strong advocates for everyone carrying Narcan,” Hurley said. “I carry Narcan as I walk to-and-from work. For me, it's a bit like a first aid thing. Anyone can give Narcan to any person that they find unresponsive. If this is not an opioid overdose, you will not make things worse. If it is an opioid overdose, you might save a life.”

If you or someone you know is experiencing an overdose, call 911 immediately. Signs of an overdose include:

- Unresponsiveness or loss of consciousness

- Small pupils

- Blueish, pale or cold skin

- Abnormal breathing

- Fast, slowed, or irregular pulse

- Nausea and vomiting

- Limp body

Have you administered Narcan recently? We want to hear about your experience. Email victoriacarodine@rmpbs.org.

Victoria Carodine is the Digital Content Producer for Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at victoriacarodine@rmpbs.org.