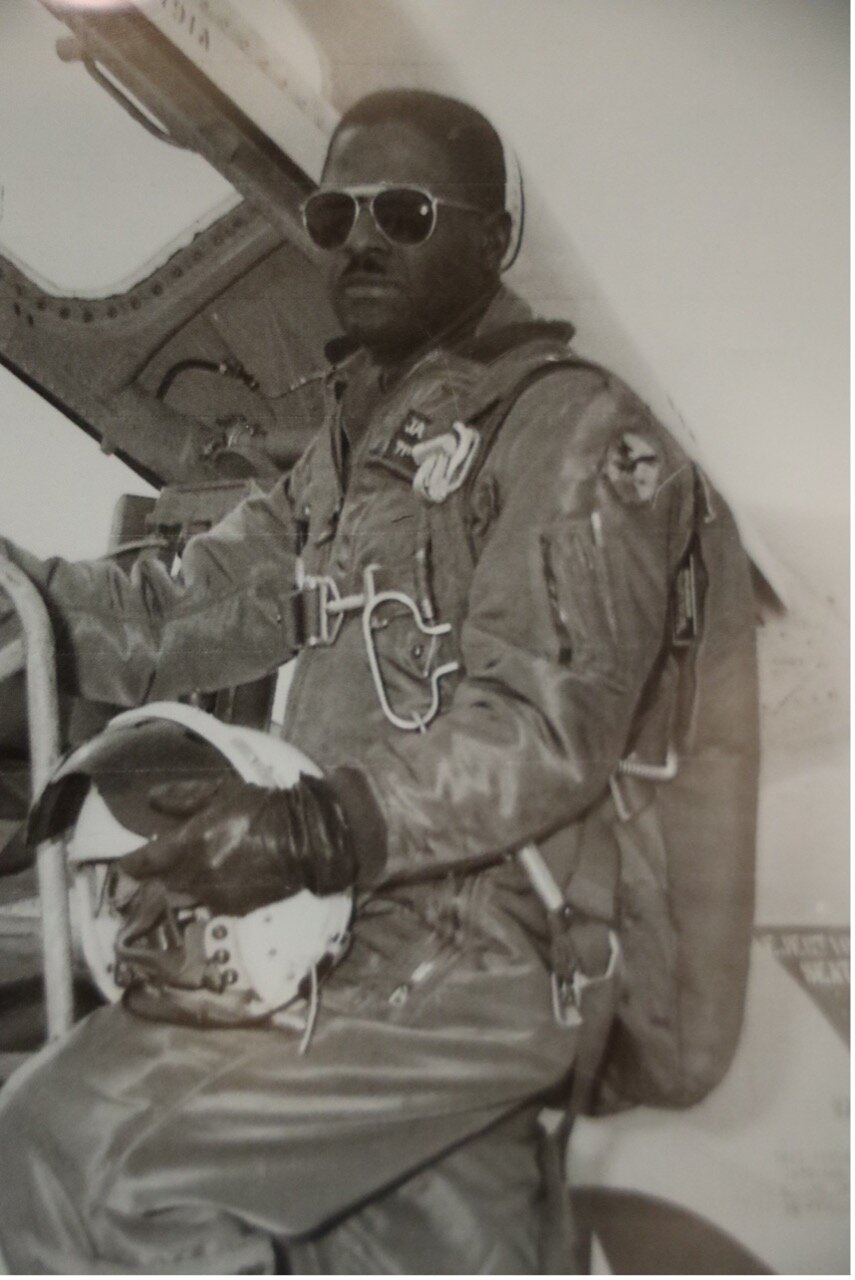

Tuskegee Airman James Harvey celebrates his 100th birthday

LAKEWOOD, Colo. — “I was a perfectionist… that carried me all the way through life really. However, when I got married, I had to knock it off,” joked Lieutenant Colonel James Harvey.

Thursday, July 13 marked Harvey's 100th birthday. When Rocky Mountain PBS met him at his home in Lakewood, he was in a refelctive mood. The past 100 years have seen him from a young boy in Montclair, New Jersey, to becoming arguably one of the most skilled aviators of World War II as a member of the famed Tuskegee Airmen. After spending the afternoon recounting his time in the service and sharing a lot of laughs, Harvey revealed himself as something of an inspirational jokester.

Growing up in a poor, but proud family, young Harvey adapted quickly to an ever-changing world when his family moved to Nuangola Station, Pennsylvania in 1936. Nuangola Station was a small mountain town and Harvey's family was the only African American family there. But Harvey recounted being treated like everyone else.

“There was not any prejudice whatsoever,” he recalled.

However, that sense of belonging would soon shift for him.

When he was at home one day and a flight of four P-40 aircrafts flew over his head, Harvey remembers saying to himself that he would like to be up in the skies one day. He tried to enlist in the Army Air Corps but was told they were not accepting enlistments at that time. He knew that had to be wrong; the military always needed more people.

“They didn't want me because of the color of my skin," he explained.

In 1943, Harvey was finally drafted into the Army and boarded a train bound for Fort Meade, Maryland where, once again, his resolve would be tested. When he arrived in Washington, D.C., he was taken out of the passenger car and transferred to the last car where Black passengers had to ride. Harvey said this was his introduction to prejudice and discrimination.

When asked how he kept his composure throughout his career while dealing with prejudice from leadership and other soldiers in his unit, Harvey said, “If you’re a perfectionist, you can do anything.”

The potential for failure stayed present in his mind and in those of his comrades, but they stayed the course with the mindset that everything they did had to be perfect. The system was designed to make them fail, but Harvey was not the type to let that happen. He set out to prove that he could learn to fly; to prove that African Americans could do anything anyone else could do, and to prove that a strong will to win can take you as far as you want.

Lieutenant Colonel James H. Harvey went on to become one of the most decorated war heroes of his time. Not only did his dream of flying come true, but he served as a member of the distinguished pursuit squadron based in Tuskegee, Alabama: The Tuskegee Airmen. Thousdands of Tuskegee Airmen trained in Alabama, but fewer than 400 were deployed. The airmen flew over 15,000 individual missions — Black airmen flew double the number of combat missions as white pilots, according to PBS — and shot down 112 enemy airplanes in World War II, according to the National World War II Museum.

In 2007, the Tuskegee Airman received a Congressional Gold Medal.

[Related: Who Are The Tuskegee Airmen? The story behind the airmen and their double victory]

Harvey was the first Black jet fighter pilot to fly missions over Japan and Korea, flying 126 combat missions throughout his career. He became one of the best, if not the best, pilots of the generation. His accomplishments speak for themselves. Most notably, being a member of the 332nd Fighter Group Gunnery Team that won the first ever “Top Gun” competition, an honor that took over 50 years to be recognized.

So, as the “ever-joking” Lt. Col. Harvey celebrates his 100th birthday, he thinks back to all the lessons that he has learned. He takes a moment and gives wise words that he believes are the key to a long, happy life: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. That’ll carry you through if you think about it. And always be truthful, have a sense of humor and have a good, good belly laugh at least once a day.”

William Peterson is a senior photojournalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach him at williampeterson@rmpbs.org.