Colorado singer recalls collaboration with Duke Ellington and unexpected career

COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. – A dining room table spills over with stacks of photo albums highlighting achievements of a single musician’s life’s work. Amidst programs and newspaper clippings in several languages, the demure face of Peggy Shivers, photographed through the decades, gazes back. Musing about her unintended success as a celebrated soprano, Shivers shrugs.

“I never set out to have a career in music,” she says. “I was just being me.”

Born in 1939 in eastern Texas, Shivers lived first in the small, rural, African American community of Center Point. The unincorporated town was originally settled by emancipated slaves in 1865. “Everything about the community was unique,” Shivers told Rocky Mountain PBS. During a time when many African Americans did not have access to education, Shivers said the academic experience found in Center Point was of particular note. She proudly credits her uncle, Larry Brown Cash, and his wife, Christine, for turning the one-room schoolhouse of Center Point into a full-fledged vocational school. Larry Cash, Treasurer of the Texas NAACP, served as principal of Center Point School. When he retired to become a Baptist minister in 1911, his wife Christine took his place, Shivers said. Christine went on to create the Center Point Training School, a 14-acre accredited K-12 community education facility, growing the schoolhouse into five classrooms and a student lab. Students worked and raised crops on school grounds, utilized an on-site cannery and mill, took college extension courses, and contributed to the building and maintenance of the structures. They were able to earn a living working at the school, which had its own store and gas station. “It was just a beautiful place,” Shivers said. “You had the feeling that you could do whatever you wanted, if you put your mind to it and worked at it. I watched children gain a lot of confidence.” Shivers said these opportunities set many community members on a path to success. “There have been a lot of very successful people to come out of Center Point,” she said. Though Shivers and her family moved to Portland, Oregon, when she was eight years old, to this day she is still in contact with families and descendants from the Center Point area. “Even after we moved, we went back every year for Homecoming,” she said. After two decades as an evolved vocational academy, Center Point Training School closed in 1950, consolidating with the school district in nearby Pittsburg, Texas. “The community then changed completely,” Shivers said. “Since then, white people have bought up a lot of the land.” Shivers recalls that her Aunt Christine, founder of the Training School, was one of the first African American women in Texas to obtain a doctorate degree. “She was not allowed to get a degree in Texas at that time,” Shivers said. “She had to go to Wisconsin to complete her PhD.”As a young girl in Center Point, “Church was very much a part of our lives,” Shivers said. “There was a lot of emphasis on music, and my whole family was very musical. We had wonderful choirs at school and at church.” Her first performance at the age of three involved soloing at their Baptist church with a song her grandmother taught her. “My family really encouraged me with music,” Shivers said. “But I think, whatever I would have done, it would have been the same.” Shivers was surrounded by talent. One of her cousins, Barbara Smith Conrad, was a world-renowned soprano, singing with the Metropolitan Opera. Barbara’s brother Denard was “a fantastic pianist,” she said, “and enjoyed working with singers.”“Each Sunday after church, we would go back to the house and practice,” Shivers said. “Denard was always teaching us something.” Her father was hired in the shipyards in Portland, and the family moved in 1947. There, Shivers further developed her talent into a classical repertoire, appearing in many church and school performances. Though music was her passion, Shivers said she always had another job to cover expenses. She began majoring in music in college at Portland State, and was part of their touring singing group.

Shivers switched her major to education after two years, and after graduating, taught second grade in Portland. She moved to San Francisco a few years later, again teaching second grade. “I continued singing — and continued studying,” she said. “And though I never went out for a music career, and I never looked for a place to sing, I always studied, and was prepared for when something did happen.” Shivers credits many teachers and mentors who looked out for her, took her under their wing, and shared their expertise, leading to further opportunities.“In a lot of my performances, I was the only African American,” Shivers said. “But I was just always committed to being myself. That was all I could do. And things just happened.” One of the things that “just happened” to Shivers was meeting and performing alongside Duke Ellington. While performing in Lost in the Stars at the San Francisco Opera Ring, Shivers was reunited with an old friend from Portland — a boxer named Amos Lincoln. She invited Lincoln and his wife to the show. “The next day, he and his wife came over with an entourage of four of five people,” Shivers said. “We were just laughing and talking, and he was steadily bragging about how good I had been in this play. Somebody in the group said, ‘Well, we should introduce her to Duke!’ I was like, ‘Duke? Duke who?’”Though she had no expectation, Lincoln called back a few hours later, having arranged for Shivers to sing for Duke’s son, Mercer Ellington, as a precursor to meeting his father. “He decided I was good enough to sing for his dad, and told me to meet them at Basin Street West, a club on Broadway,” she recalls. The nightclub was renowned for its jazz shows. Shivers didn’t want to go there alone.“So, I called my minister,” she laughs. “And he went down with me.”

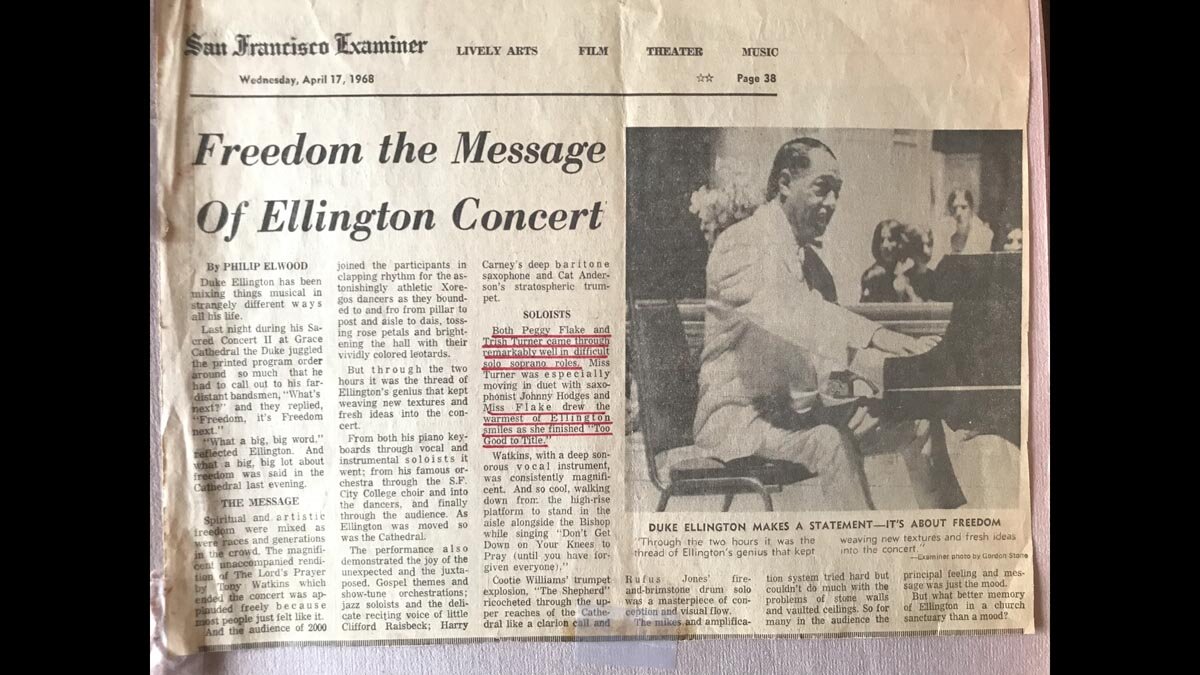

They sat through two intermissions, then through the end of the show, without Ellington acknowledging them. Finally, as the musicians were packing up their instruments, Ellington turned to Shivers.“He said, ‘Stand up, and start singing, then,’” Shivers said. She refused. “I said, ‘If you want me to sing, go to the piano, and treat me like a lady — and I will sing for you.’ Evidently, that made an impression on him. He took me down to the piano.”Shivers nailed the audition by singing intervals. From then on, any time Ellington was going to perform in the Bay area, Shivers said, he would call and leave two tickets for her.“He always called very early in the morning,” she remembers. “One day he called at three a.m. and asked if I was singing anyplace. I just happened to be doing a concert. I will always remember him coming in, and how surprised the audience was.”Shivers said another friend of hers, Dell Graham, mother of bassist Larry Graham from Sly and the Family Stone, also happened to attend that night’s concert. “So, I had these beautiful musicians right there,” she said. After seeing her perform, Ellington invited Shivers to sing at his Sacred Concert at San Francisco’s Grace Cathedral. “It was a great, great experience,” she said. “A lot of people assume that since I was singing with Duke Ellington, I was singing jazz. I wasn’t. For the Sacred Concert, my classical voice fit quite well, because there were many high notes. I think my high range is what impressed Duke.”

Through her brother, she met her future husband, Clarence Shivers. They married in 1968. The next year, Clarence retired from the military. He had made history as a Tuskegee Airman, one of the first Black military pilots in the United States Armed Forces during World War II. “They referred to the program he was in as ‘The Tuskegee Experiment,’” Shivers said. “At that time, it was thought by the military that African Americans could only do menial jobs, like cooking, cleaning, and that sort of thing. There was a movement in the Black newspapers and the NAACP against this, that then pushed the military to decide that they were going to prove that African Americans couldn’t do anything beyond those jobs.” “Needless to say, these men proved them completely wrong,” Shivers said. In 1941, after taking an entrance exam, Clarence received high marks and was entered into the elite Tuskegee Program — the first training for Black pilots. “As a result of how well they did, the military became integrated,” Shivers said. “Then, more integration took place around the country in general. So, they played a big role in the history of race relations in our country. The Tuskegee Airmen were amazing men. They really were. Many went on to do great things.” Shivers said her husband experienced tremendous racism, especially in his early years in the military. “Clarence was a bit disenfranchised as far as the military,” she said. “Can you imagine, being African American in the military before it was integrated? He’d had some… experiences.” After World War II, Clarence went on to finish college, then taught art at Jackson State University until he returned to military service during the Korean War. He remained in the Air Force until 1969, retiring with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. After his retirement, the couple moved to Spain, where they lived for ten years. There, Shivers continued to perform professionally. Clarence, a lifelong artist, was able to paint full time for the first time in his life, as well as teach art. He became well known throughout Europe for his colorful abstract paintings. In 1979, the couple relocated to Colorado Springs and bought a house, Shivers said. It’s the house where she still resides. Although she was sad, at first, to leave Spain, Shivers said about moving to Colorado Springs, “We made the right decision.”

“But Colorado Springs was a very conservative area in the 70s and 80s,” Shivers said. “Historically, the KKK had a big hold in this area. However, somehow, we have gotten just tremendous support. I really appreciate how the community came together for us.” In Colorado Springs, Shivers quickly acclimated to the cultural scene, including an invitation to sing at the Fine Arts Center, and another to become the first African American television host in Colorado Springs history, appearing on KKTV. She soon began working with the Colorado Springs Symphony and the Colorado Springs Chorale, while Clarence maintained an active art practice. In 1985, Clarence was commissioned to sculpt a life-sized statue as a memorial to the Tuskegee Airmen. It was unveiled May of 1988 and stands on the grounds of the US Air Force Academy.In 1993, for their 25th wedding anniversary, the Shivers threw a five-day festival, bringing friends together from near and far for a week of music and art experiences. In the middle of the celebration, Clarence got sick, and wound up in the hospital, Shivers said, undergoing a triple bypass surgery. Afterward, using the money from the sales of the week’s art, they created the Shivers Fund to help bring African American books and materials into circulation at Pikes Peak Library District. The Shivers African American Historical and Cultural Collection now contains more than 400 works. “I wanted the Library to have more representation of African American works of, by, and for African Americans in their collections,” Shivers said. She was adamant the collection be intermixed into the library’s main collection, and that there not be a separate area for the works.And as for the music festival, “All our friends had such a good time, they asked us to do it again,” Shivers said. So, she started the Shivers Concert Series, inviting local, national, and international talent to take to stages across Colorado Springs at events throughout the year. The Shivers Fund and Shivers Concert Series have won numerous awards for community service, philanthropy, and equity, including for work in providing scholarships to young people interested in the study of classical performing and visual arts. Clarence passed in 2007, and since, Shivers has carried on their legacy with the help of the community. “We really found ourselves a wonderful home here in Colorado Springs,” Shivers reflects. “It has just been a joy. I just love it here.” Shivers said she has remained homebound for much of the last year’s pandemic and is looking forward to returning to planning her concert series for the community when the time comes. Her greatest wish, she said, is to solidify the legacy of the Shivers Fund and Concert Series.“I’m getting up in age,” she said. “I would like to start making plans about how it is all going to carry on, even after I’m long gone.”