Citizen scientist group warns of rising water temperatures, drought on the Western Slope

BASALT, Colo. — Dry soils topped with a below-average snowpack in the 2020-2021 winter season produced a dire situation for folks across Colorado's Western Slope.

With drought came historically low river flows, and with less volume to cool the waterways of the Roaring Fork Watershed, temperatures rose to life-threatening levels for Colorado's aquatic wildlife. The group responsible for relaying local water temperatures says it is a problem that has become all too common.

Hot Spots for Trout, the brainchild of the Roaring Fork Conservancy (RFC), was created in the wake of the 2002 drought to help collect water data and keep an eye on the health of the watershed's rivers. The group of volunteer citizen scientists record water temperatures around the watershed for the conservancy, which in turn recommends fishing closures to Colorado Parks and Wildlife when the temperatures get too high. Hot Spots has been called to action in three of the last four years.

"We can't say that we’re completely surprised when we’re receiving warm water temperatures in the middle of July, for example,” said RFC community outreach director Christina Medved. “What is surprising is how often the temperatures go above 70 degrees.”

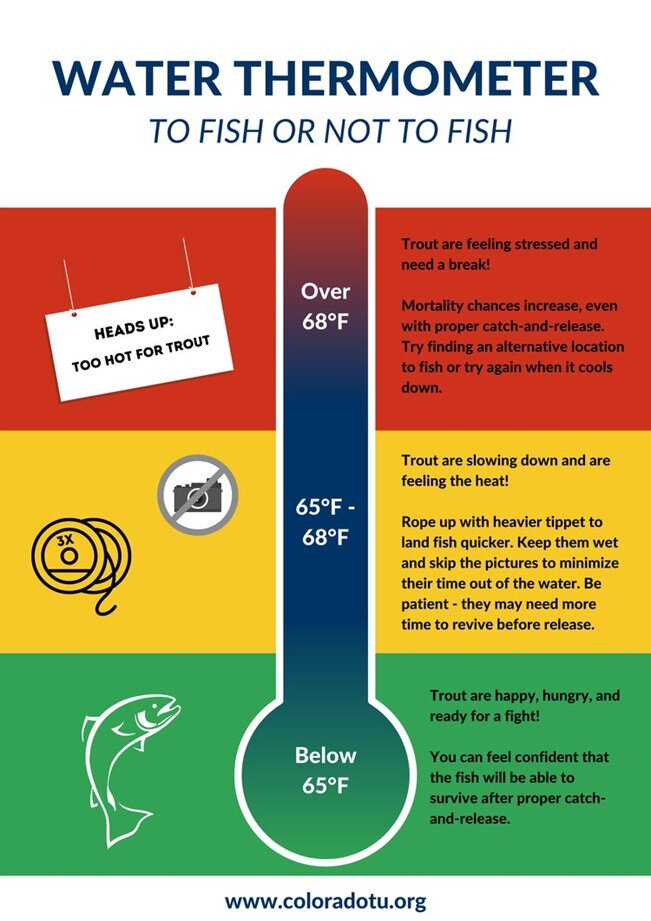

When water temperatures rise to such elevated levels (68 degrees and above), caught-and-released fish struggle to fully recover. Warmer water contains less oxygen, making breathing harder for the fish.

This past summer, 23 volunteers answered RFC’s call for help, including Ted Bhar, a local enthusiast with over 50 years of experience in the outdoors. Rocky Mountain PBS met with Bhar along the Fryingpan River in late September—a world-renowned destination for fly fishing just outside of Basalt. While temperatures were adequate to support healthy fish life when we met with Bhar, signs of drought were hiding just up-river at Ruedi Reservoir.

"The temperatures here are terrific, they’re 48 degrees,” Bhar noted. “If we just said this is all we care about—if we didn’t understand the bigger picture—we’d say, ‘Well, everything is great!’”

As a result of the low flows throughout the Colorado River over the summer, more water had been allocated from reservoirs like Ruedi to meet the demand of an estimated 40 million people downstream.

The Fryingpan, which was being used as an aqueduct to support the Colorado River, remained cool with flows nearly 165 percent higher than normal at the time of our visit.

Related Stories

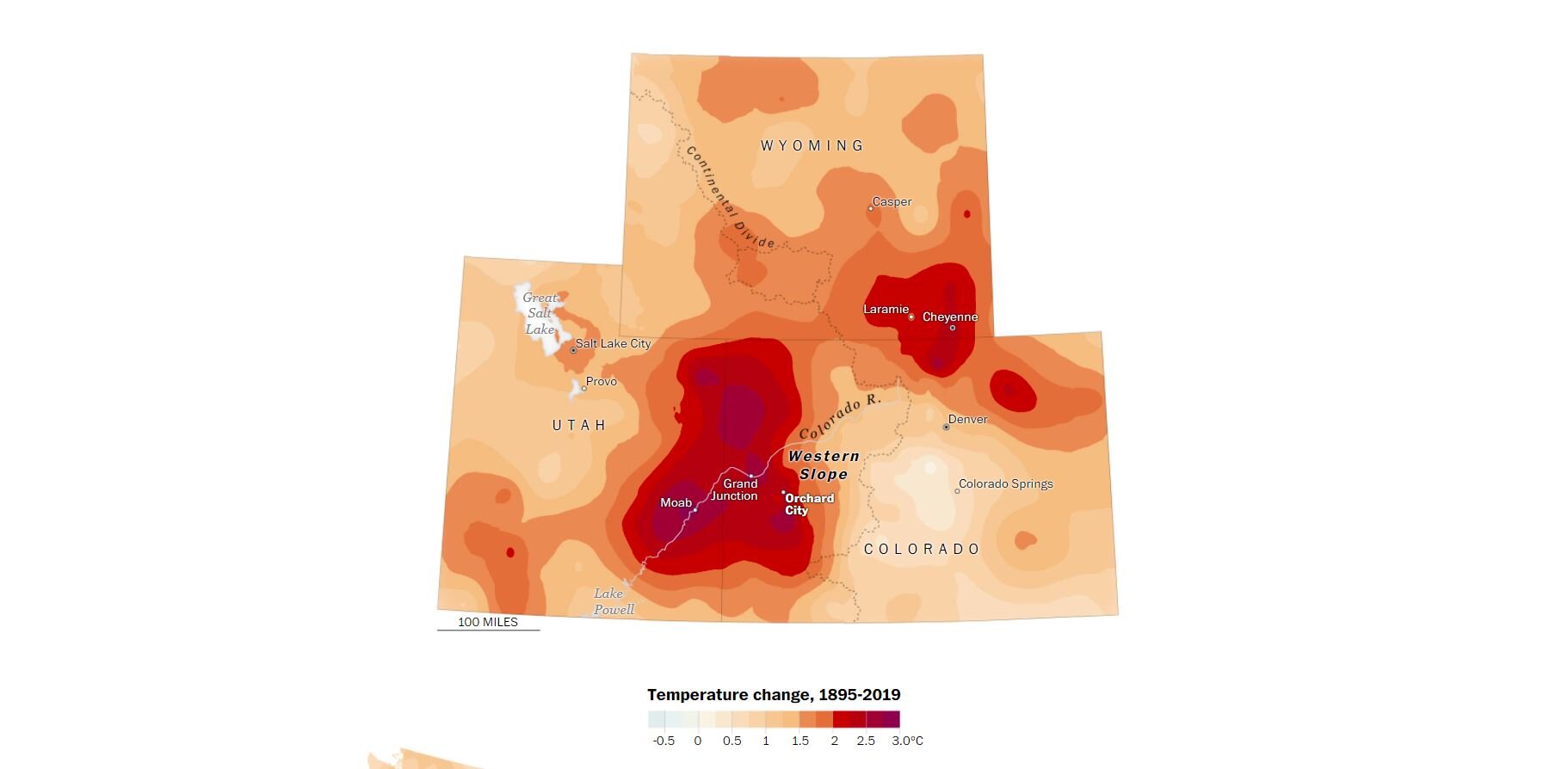

The Natural Resources Conservation Service found that Colorado has experienced decreasing snowpack averages since at least 1984. This coincides with the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) temperature change map which shows rising average temperatures in Colorado. According to data compiled by The Washington Post, parts of the Western Slope have warmed by more than 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit, doubling the global average.

"When we use the word drought, it implies that we’re going to get out of it pretty quickly,” said Medved. “What we’re experiencing here in western Colorado and in the West is that we’ve seen a 20–year pattern of decreased precipitation and snowfall, and so we’re seeing the start of our climate go from semi-arid, to an arid environment. They’re calling it 'aridification.'”

According to the latest map from the U.S. Drought Monitor, most of Colorado is experiencing drought conditions, ranging from "abnormally dry" to "exceptional drought." You can see the latest data—updated with new maps every Thursday—at this link.

The incoming winter season provides an opportunity for Colorado to escape drought in its Western counties. As a headwater state, Colorado relies on snowmelt to produce as much as 80 percent of its total water supply. With a lack of snowfall in the 2020-2021 winter season largely contributing to this year's drought, it will be vital for snow to return this upcoming season and in great numbers.

[Related: La Niña is coming. Here's what that means for winter weather in the U.S.]

“The old adage that 'Whiskey is for drinking and water is for fighting.' The fact of the matter is that water and the access to that water is all about the ability to lead a human life,” said Bhar. “Without water we can’t do any of this: We can’t live, we can’t drink, we can’t survive."

Matt Thornton is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. He is based in Grand Junction. You can contact him at matthewthornton@rmpbs.org.

While the Fryingpan River seemed healthy, the sight at Ruedi was much different. Horizontal descending lines surrounded the perimeter of the reservoir, a result of the lowered capacity due from water allocations and the drought itself. Days prior, the U.S. Forest Service pulled the boat dock from the water, as the water line had crept below the paved ramp and into the mud below. Sights like this have become common across the western slope, where places like Blue Mesa Reservoir also experienced lowered levels and even a toxic algae due to the heat.

“In just the time since I've been to Colorado, I've notice changes, and I've notice that [the] system is under extreme stress,” Bhar explained. “There are some times of the year, and times of the day that I shouldn't be fishing certain rivers when, perhaps, years ago I could have easily fished them.”

According to the conservancy, rivers within the Roaring Fork Watershed have reached alarmingly low levels in summer months, with stretches of the Crystal River running as low as nine percent. To some degree, this is to be expected.