The Great Pueblo Flood, 100 years later

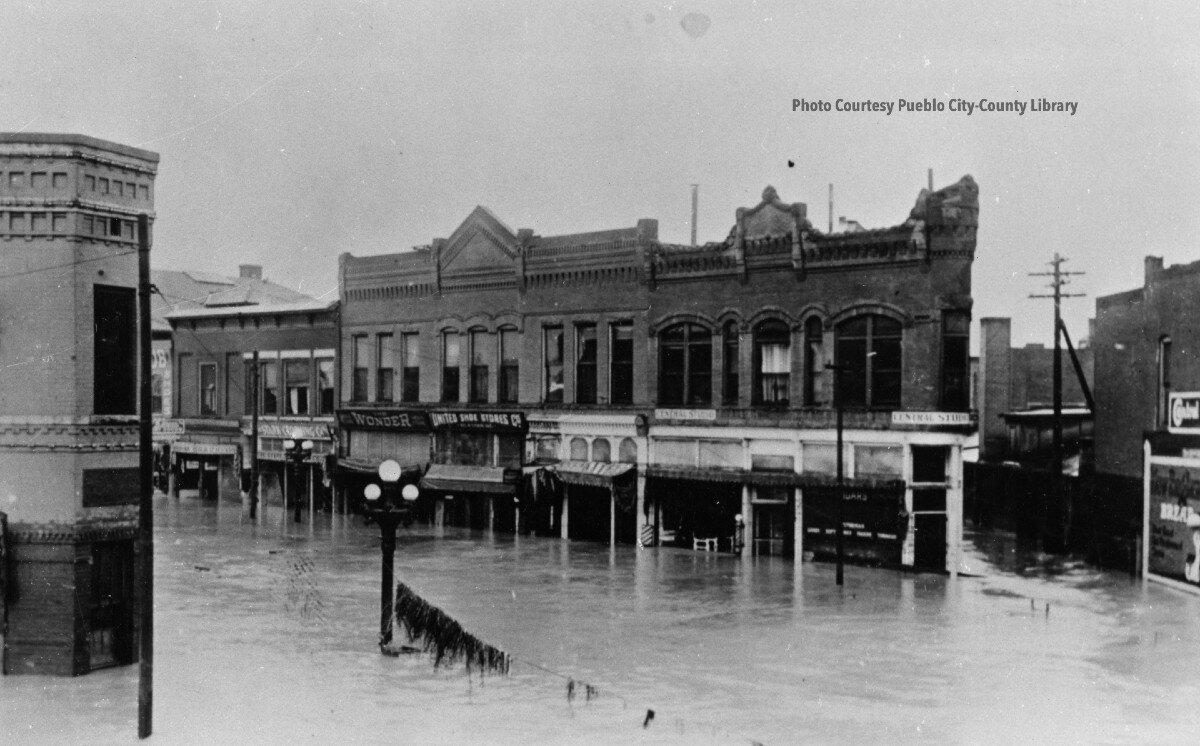

PUEBLO, Colo. — Thursday, June 3 marks the 100th anniversary of one of the deadliest natural disasters in Colorado history. In early June of 1921, Pueblo experienced a devastating flood that destroyed much of the downtown area. The very river that formerly brought life and sustenance to the region now left death and destruction in its wake.

Cora Rockefeller survived the flood and described the devastation. This excerpt comes from the June 9, 1921 edition of the Western Star, later reprinted in the Pueblo Lore:

“Read the worst you can and believe it. I shall not try to describe it except to say the stricken district is utter dissolution. The newspaper writers with their facts cannot give you half the picture. No one can say with certainty whether 500 or 5,000 lost their lives. It probably never will be known. Bodies are being brought in everyday from miles down the river. The rush of water was so terrific that hundreds must have been washed downstream and never will be found.”

Without weather forecasts and sirens to warn people, the flood’s devastation was massive. Two passenger trains, with an estimated 200 people on board, were caught in the flood. Floating rafts of burning lumber moved through the city, spreading fire and destruction. Pueblo was placed under Martial Law. About 1,500 local men were deputized, and Colorado Rangers and military units were brought in to ensure security. Orders were given for looters to be shot on sight.

A century later, the river has been tamed by a dam and a levee, and the Historical Arkansas River Project is the centerpiece of a development effort that is changing the face of the city.

When Justin Bregar suggested in the summer of 2020 that we produce a documentary about the “Great Flood,” we were both immediately intrigued. We were also aware that the upcoming 100th anniversary meant that we would have to move quickly. We knew little about the flood, but we were fascinated by the Arkansas River’s old and new channels that bisected the city of Pueblo, the levee that protected the city from high water, and the role that the Lake Pueblo Dam played in regulating the heavy flows during the runoff season of early summer and during times of intense rainfall.

The flood of 1921 predated all of these flood-control measures and we quickly realized that these engineering feats were all connected by a desire for safety and security, something that had eluded this city founded at the junction of two rivers. The Arkansas River, which collects snowmelt and rainfall from the largest river basin in the state of Colorado, is joined in Pueblo by Fountain Creek, an unruly stream that, prior to the 1990s, ran dry every summer between bursts of torrential flows that coincided with heavy precipitation.

We shared the idea with Rocky Mountain PBS and they in turn helped us look for underwriting support from the Pueblo Community. Before we knew it, we were on our way researching history of death and destruction, as well as that of recovery, resilience and renewal. The community came together to provide information and resources that we would need to share the experience of individuals who lived through the ordeal; those who shared their experience with family and friends who then shared them with us.

Local historians and historical societies were quick to lend their expertise, photos, and other memorabilia for the documentary. Almost unbelievable historic film footage shot by two filmmakers who just happened to be in Pueblo at the exact time of the flood was located by the local library staff and digitized. Local business owners whose parents and grandparents lost everything to the rushing water shared stories about their will to rebuild what had been washed away by the raging torrent. We learned about Lucky the Horse, a horse mannequin that belongs to a local saddle shop. We also discovered that prohibition was temporarily lifted in Pueblo for medicinal purposes.

Joseph Koncilja, an attorney who appears in the documentary, explains that in the early 1900s, “you could get free passage to Pueblo from your country of origin if you agreed to sign on to work at the steel mill. And so thousands of people, from all over the world, came to Colorado with the understanding that they would work in the steel mill.”

Lawrence Green, a Pueblo Historian who also appears in the documentary, explains that “one of the reasons why [Colorado Fuel and Iron] was located in Pueblo, is that it's in the middle of the basic materials needed to make steel: coal from the fields in Florence and in Trinidad, iron ore was mined in Orient in the San Luis Valley, water was fairly readily available; and CF&I grew at a time when railroads were in need of building materials. It all came together at the same time.”

Pueblo’s population of immigrants, who came to work for the largest steel mill west of the Mississippi River, were accustomed to facing adversity. But nothing could have prepared them for the challenges they faced when the full force of nature was unleashed on the city in June of 1921. Over 600 homes were destroyed in Pueblo by The Great Flood, while another 350 were so badly damaged that they were condemned. Estimates of property damage approached $20,000,000.

Stories about heroes were plentiful, including the telephone operators who stayed at their posts, calling everyone they could reach who lived downstream of the raging waters. But despite the heroic efforts of many, the flood claimed hundreds of victims. Debates continue to this day over just how many lives were lost, with estimates ranging from the low hundreds to thousands.

The number of train cars lost to the flood was well documented, as was the property damage, but the human toll was woefully neglected. At that time, people of color weren’t counted correctly, and families were lumped together and counted as one, i.e. “1 family of color,” with no count of how many people in the family actually perished. Wade Broadhead, an Historic Preservation Specialist who appears in the documentary says, “Probably a lot more people died in the Pueblo flood than will ever be documented because they weren't documented. They were undocumented immigrants. They couldn't speak English and whole families were washed away. Sometimes we have no record of those people. In that respect, it's horrible. And then it's also horrible because we don't even know what we lost in some ways. And we'll never know.”

Jonathan Rees, a history professor at CSU Pueblo who appears in the documentary elaborates: “The first thing you have to understand when you talk about casualties is that the people who were running Pueblo had no interest in documenting the exact number of casualties. You can take that statement and say that it must have been much higher because they must have been covering something up. Or you can take that statement and say, well, they're not really interested in it because they're more concerned about fixing the economic damage.”

The railroads were an essential component in the early success of Pueblo. A central hub for both east/west and north/south traffic, rail lines in and out of Pueblo linked Colorado with an expanding Western region. And in the process of researching and producing this program we learned that Pueblo’s delegates decided to broker a deal with legislators from Northern Colorado that, in time, led to the economic decline of Pueblo. Donald Banner, a Pueblo attorney who appears in the documentary says that “after that flood and after everything that occurred after that flood, Pueblo lost its prominence throughout the nation as one of the largest rail yards and intersections of rail lines in the whole United States. That changed the commerce in the United States. It changed the way people did business in Pueblo, Colorado.”

We also discovered the devastating effect of redlining in Pueblo. This New Deal policy targeted poor neighborhoods across the country. In Pueblo, these neighborhoods were often occupied by minorities, and were in the low-lying areas in the rivers’ floodplains. Rees explains that “redlining is something that comes out of the New Deal when the government begins to subsidize loans to people to help them stay in their homes during the Depression. They created maps that suggested what are the best neighborhoods in every city in the country for banks to loan to.”

The maps were color-coded: Green (“Best”), Blue (“Still Desirable”), Yellow (“Definitely Declining”) and Red (“Hazardous”). Blue areas were explicitly white homogenous, while Red areas were described by the Home Owner’s Loan Coalition as having an “undesirable population” (historically, African American residents) and were ineligible for FHA backing. The effects of redlining persist in Pueblo today.

We also learned that the original levee and the movement of the river channel was a tremendous undertaking that resulted in long-term protection and economic stability for downtown Pueblo businesses. Restoration of the original levee, as ordered by FEMA, and redevelopment of the original river channel are opening up new opportunities for a historic downtown and river that, once again, enhances the quality of life for those who live nearby.

Banner shares, “I think we're a community where we're not afraid to roll up our sleeves and meet the challenges that the future will bring up. I think that started with the 1921 flood.”

Indeed, this documentary could only have happened as a community effort. We received photos, footage and support from The Pueblo City-Country Library, Pueblo County Historical Society, Steelworks Center of the West, Watertower Place, Pueblo Memorial Hall, CSU Pueblo, Denver Public Library and History Colorado. The film features many Puebloans, who graciously lent us their time and expertise. I thank them publicly here (in alphabetical order):

- Susan Adamich - Historian, Pueblo Heritage Museum

- Don Banner -Attorney, Banner & Bower

- Wade Broadhead - Historic Preservation Specialist

- Lucille Corsentino - President, Roselawn Foundation

- Michael Cuppy - Principal VP, NorthStar Engineering

- John Ercul - Former Deputy Police Chief, Pueblo

- Lawrence Green - Historian

- Greg Heavener - Meteorologist, NWS

- Gregory Howell - Creative Consultant, Watertower Place

- Joseph Koncilja - Attorney, Koncilja and Koncilja

- John Korber - Historian

- Spencer Little - Outreach Coordinator, Pueblo Heritage Museum

- Jonathan Rees - Professor, CSU Pueblo

- David Rush - Owner, Rush’s Lumber

- Therese Simony - Pueblo Native

- Mike Strescino - Artist

- Peter Strescino – Former Journalist

Susan Adamich, an Historian with the Pueblo Heritage Museum who is featured in the documentary says, “We're taking a bad piece of history and turning it into a positive place. That would be a thing to tell people about Pueblo's flood. Come see what we've made of the disaster. Come see the beautiful river walk we have today.”

“The Great Pueblo Flood”, a one-hour episode of Colorado Experience premieres June 3rd at 7pm on Rocky Mountain PBS. It was generously funded by Pueblo County, Pueblo Urban Renewal Authority, The City of Pueblo, PB&T Bank, Wilcoxson Wealth Management, Sangre de Cristo Arts & Conference Center, Historic Pueblo Inc., The Ceres Foundation, Deanna E. La Camera and Hassel and Marianne Ledbetter. The community engagement event was generously sponsored by The Rawlings Foundation.

Samuel Ebersole (writer/producer of "The Great Pueblo Flood") has been a professor in the Media Communications Department at CSU Pueblo since 1990 and has written and produced several documentaries that have aired on Rocky Mountain PBS.