Coloradans discuss the 'friends, family and neighbor' network of child care

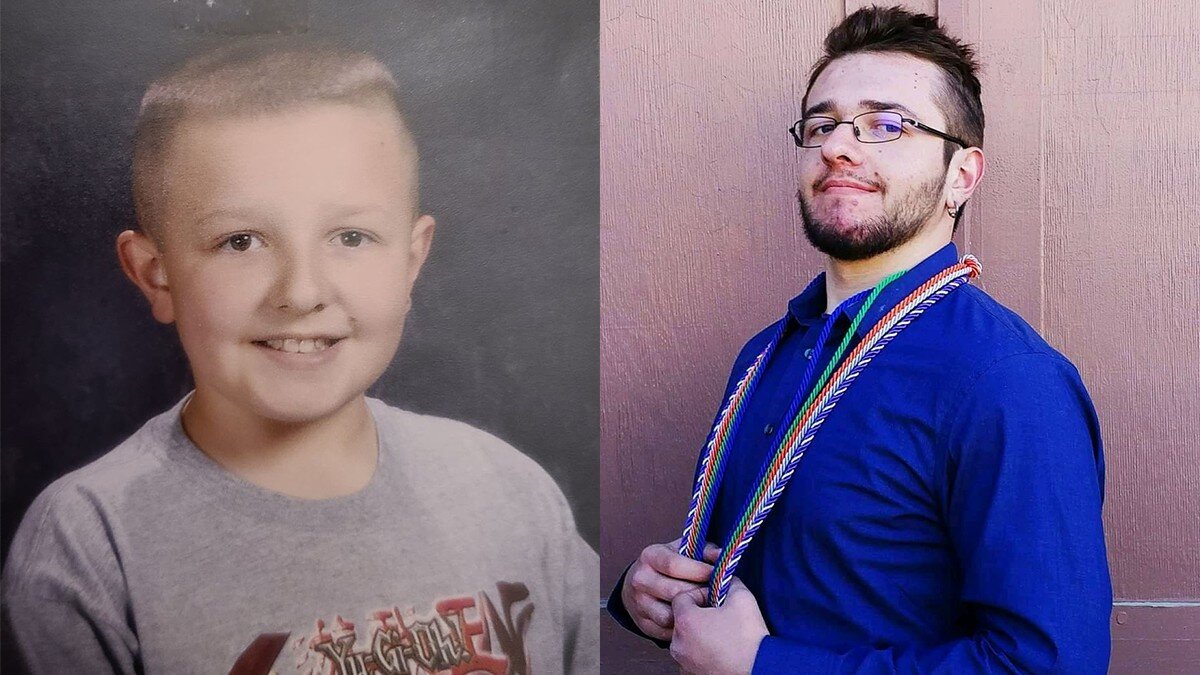

DENVER — Michael Villafuerte remembers being 5 years old when his parents first started leaving him at home alone. Sometimes, his mom would take him to work, but for the most part, Villafuerte watched PBS Kids and animal shows, or played video games.

Villafuerte’s younger sister was in daycare until she was 3 years old. After that, she started staying at home with him, too.

For food, they would have a bowl of cereal for breakfast; for lunch, they made sandwiches. Their parents were home by 5 or 6 p.m. to make them dinner.

When families in Colorado don't utilize daycare centers, they often turn to the family, friend and neighbor (FFN) caregiving network.

A report by Mile High United Way, which studied the impact of COVID-19 on FFN caregiving, stated that FFN caregiving is the most common form of nonparental care in the United States. FFN caregiving gives families a trusted, affordable and flexible child care option. Child care is often prohibitively expensive in Colorado. According to the governor's office, "infant care costs nearly 10 percent more than the average rent." Moreover, a recent fact sheet from the Biden administration reported that the annual cost of a child care center for a toddler in Colorado is $14,300.

But when families don't have access to daycare or FFN support systems, they don't always have a choice but to leave children home alone.

The biggest reasons why they were left home alone, Villafuerte said, were financial constraints, the long distance to daycare and their parents’ trust to take care of themselves.

According to a blog post by CO4Kids, a state-run campaign to raise awareness of ways to prevent child abuse and neglect, there is not a specific age in Colorado when a child legally can stay home alone, though Colorado has generally accepted the ages of 10 to be alone and 12 to babysit as a standard based on the state's Child Labor Law.

Looking back, Villafuerte isn’t sure if he would consider his experience being left home alone as child neglect, as he said always felt safe. He and his sister walked to school because the school was only three blocks away from their home. And after school, their mom always called to make sure that they got home safely.

“I know nowadays people try to not leave kids alone … but looking back on my life, I was like, that was kind of it. You were taught when someone knocked on the door, you don't answer it. You turn stuff down and pretend you're not home. You don't look outside,” Villafuerte said.

More trust in family than daycares, police or child protective services

Marco Esquivel said that he and his younger sister started watching their cousins when they were around 8 years old.

Esquivel told Rocky Mountain PBS that, normally, he and his sister had no problems watching their cousins. They watched TV and sometimes went to the College View Elementary School playground nearby. Esquivel’s mom and aunt always made sure that the kids had food to eat before they left.

Esquivel added that while he believes that children that are too young to watch themselves shouldn’t be watching other children, he thinks that they did not go to daycare because daycare was extremely expensive for his mom, a single parent.

Growing up, Esquivel also knew several friends with similar childhood experiences being left home alone at around 6 years old because they did not always have someone to watch them.

“I always thought that was kind of normal, but I do now see how dangerous that can be,” Esquivel said.

Once, a neighbor called the police on the kids. The police visited the home and urged the kids to let them inside. None of the kids opened the door.

“We were just sitting there in the quiet — in the dark — for two, three hours. They kept trying to get in the house and get us to open the door,” Esquivel said. “But we couldn’t do anything because we knew as soon as we opened the door, a lot of people were gonna get in trouble.”

Looking back, Esquivel thinks that he still wouldn’t have opened the door if he had to go through that experience again.

“I knew there were a lot of issues in the house, and this would have just been another one that would have made things much harder for us. It was scary, but it was not worth upending our lives over this – something I’d done a hundred times and kept doing way after,” Esquivel said.

For Esquivel, now 25, the police, the foster care system and the threat of being taken away from his family were scarier than caring for his cousins at a young age. He believes that, a lot of the time, police officers are tasked to find something wrong in a household and expressed concern about parents being unnecessarily punished.

He added that sometimes parents also deal with difficult circumstances, like having to work overnight to make ends meet, that leave them no choice but to have their kids home alone at night.

“Even in the case when I was there alone with my sister at night, all night, I don’t think anything wrong was necessarily going on,” Esquivel said. “We were just watching Sailor Moon.”

Utilizing community and family relationships to support children

Phuong Tran grew up familiar with the FFN caregiving system. Because her mom had little money and support resources when Phuong was growing up, she was either taken care of by a Vietnamese neighbor her mom trusted or left home alone.

Because Phuong grew up with FFN care, she said that she would prefer relying on FFN care rather than daycares for her future children.

"If I had kids, I would send my kids to friends or family," Phuong said. "I know I can contact them. They can be honest with me."

According to the Mile High United Way report, families choose FFN care for a variety of reasons, such cultural responsiveness, desire for nurturing care, cost and convenience.

Phuong herself has also been a FFN caregiver. She started taking care of her niece when she was around 18 years old and also worked at Strive Prep - Ruby Hill, a nearby K-5 school, and took care of children there. Phuong said because she loves kids, she didn’t mind taking care of children, going to work and going to school at the same time.

Phuong also regularly tutors two children: 7-year-old Jayden and 12-year-old Tiffany Tran.

Jayden, Tiffany and their younger five-year-old brother don't live with their parents, who work long hours and cannot always see them. Instead, the kids all live in a house with their two aunts on their father’s side.

On Sundays, the kids attend Sunday school at a local Vietnamese church for three hours; they take karate classes on Tuesdays and Thursdays; on Saturdays, they meet with Phuong to work on their math, reading and writing. The kids see their parents every Monday, and the family spends the day together.

At home with their aunts, Tiffany likes to draw and take naps while Jayden prefers playing Roblox or making parks out of Legos.

Tiffany emphasized that she is happier staying with her aunts rather than going to a daycare. Staying with her aunts means staying in a trusted and secure home.

"I prefer the way they do things," Tiffany said.

Theresa Ho is the RMPBS Kids digital content producer. You can reach her at theresaho@rmpbs.org.