'Shoe project' teaches first graders empathy and perseverance through a global lens

ESTES PARK, Colo. — When asking a first grader how they practice empathy in their day to day lives, you’ll commonly hear answers like “I help friends if they fall down” or “I hug people when they’re crying.”

And while these are valuable, touching insights, have you ever heard a first grader say “I use an empathy-based design process to design shoes for children in other countries?”

At Estes Park Elementary School, this might just be the answer you get.

Design thinking

In 2019 computer, science, library and technology integration teacher Polly Greenblatt set a professional goal to implement the design thinking process into classroom curriculums.

Design thinking is a nonlinear 5-step method of innovation and invention, but instead of the goal being success or money, the focus is to create effective solutions for others through the practice of radical empathy.

“I think it’s important to include empathy in curriculums because we’ve become such a global society, but we all still kind of live in our own little bubble, especially up here in Estes Park.We’re a small, rural town. Some of our kids don’t really go outside of Estes Park very much,” said Greenblatt.

Greenblatt decided the best product to develop with this process would be a pair of shoes. She said that she noticed that when first graders tried designing a backpack for a friend, they would focus on their own needs and desires in the design process.

“I was looking for something that they really understood. They knew what it was, it wasn't too far out of the realm of their own little reality, but it was completely removed from themselves,” she recalled.

Greenblatt ideated around the idea of school -- the fact that many children around the world had schools, but that the ways they got there varied greatly. This is where she landed on the idea of shoes.

The concept was that students would research the commute to school children from different regions of the world experienced, then create a shoe design to help the children have a safer, more comfortable way to get to class.

Unfortunately, COVID-19 hit right about when Greenblatt had begun to implement the process. This year, she partnered with first grade teacher Taylor Bodin to try again.

Greenblatt, (left) and Bodin (right) partnered in implementing a 'design thinking' project for first graders.

As luck would have it, Bodin had significant connections in the shoe industry.

“As a teacher, well, a lot of us need extra jobs,” explained Bodin, “So my other life is running. I'm a coach.”

Through his running career, Bodin gained the opportunity to test out shoe brands. One of those was the acclaimed shoe company Merrell.

Bodin tapped his contacts at Merrell and a partnership was formed. Merrell agreed to not only be interviewed by students to share their design process, but also to create digital prototypes of the designs students created.

Soon enough, the students were diving into design thinking. They began by designing something for a friend to exercise empathy practices. Eventually, they were confident enough to help solve problems for kids in other countries -- kids they had never met.

The process started with gaining an in-depth understanding of the day-to-day life of the children in the region the students were focused on.

They watched documentaries, researched and even did an obstacle course where they walked on Legos without shoes to better understand the challenges children in other regions faced on their long walks.

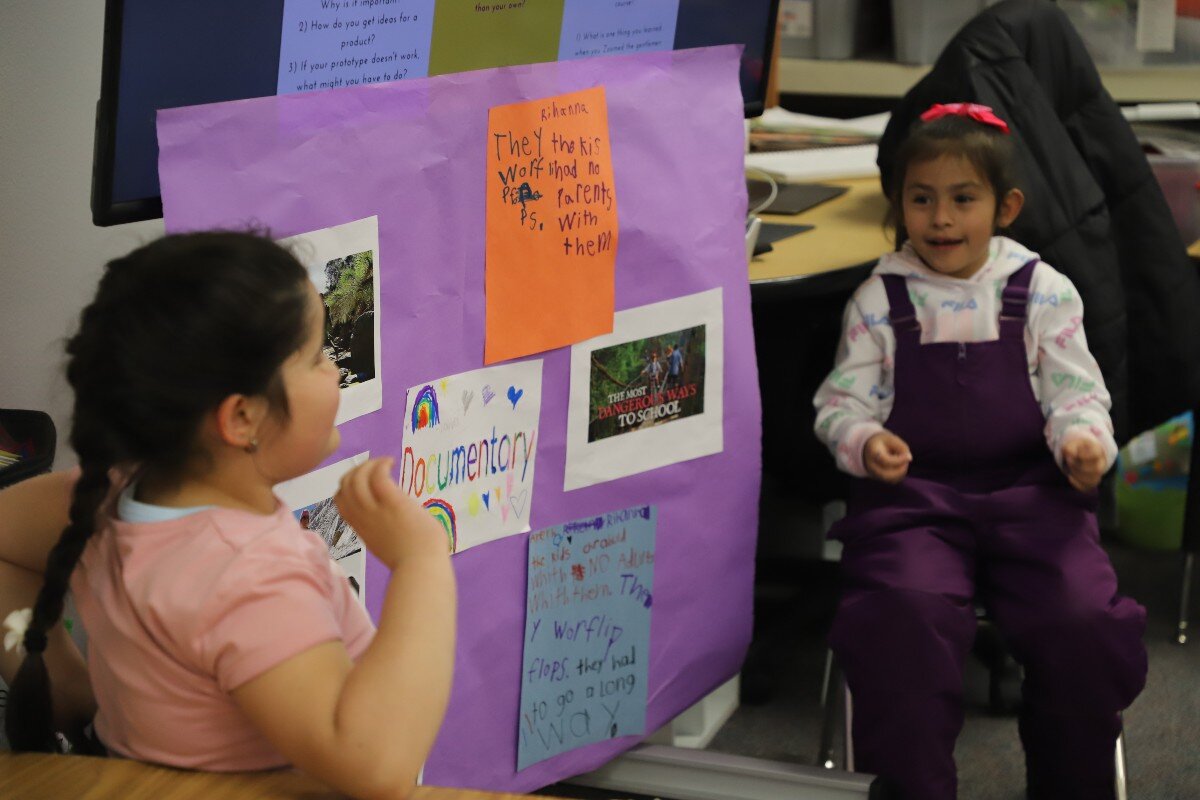

Students excitedly present their research findings to classmates.

Animal adaptability as inspiration

Next came synthesizing the information and determining the specific needs the children in other regions had. Once the students had a good grasp of the issues they wanted to address, they were free to brainstorm to their heart’s desire.

To help guide the process and deepen the learning on a scientific level, students were prompted to use animal adaptability traits to help design their prototypes.This was the part Greenblatt found to be the most inspiring.

“Elementary kids can do way more than we think,” she said. “They really don't have the constraints in their brain of, ‘Oh, that's not possible,’ or ‘That's gonna cost too much money.’”

One example of these limitless ideas in action was a student’s connection to the adaptability of starfish.

“He came up with the idea that like, starfish grow and if we made shoes out of a starfish type skin, that it could grow with the kid as their foot was growing. And just ideas like that, that they might not be possible right in this moment, but they're going to be, and maybe that kid is the kid that's gonna make that happen,” she recalled.

Bodin was inspired by the application of the Komodo Dragon to one of the shoe designs.

“They knew a lot about the Komodo Dragon, its skin, the bacteria in its mouth, and they were able to use their favorite part about it, the armored type skin to lay over top of their shoe, to help that other student feel protected from the elements,” he shared.

Perseverance through prototyping

Once their ideas were generated, the students were able to put them to the test. If an idea didn’t work toward their goal, they were encouraged not to give up, but instead to go back in the process and adjust, or try a new idea.

“Perseverance, at Estes Park Elementary School, is one of our what we call ‘global outcomes,” Greenblatt explained. “It's one of those big ideas that we want kids to have as a skill along with math and reading.”

Rocky Mountain PBS joined the first graders on their “Celebration of Learning,” day, where parents and friends were invited to see the designs the students created, as well as witness the unveiling of Merrel’s digital prototypes.

The event also acted as a launch for an ongoing shoe drive, where shoes can be sent to different global regions in an effort to help impoverished countries generate income.

According to Bodin, turnout and was better than he had expected. The halls were packed with excitement, and the communal support was palpable.

Empathy: Not always an instinct

While the children learned elements of science, geography and even art in the process, teachers were sure to return to empathy as the core element of learning. Although kids can be great at being kind to their friends — like adults — the next level of empathy for those outside their social circles can be more challenging.

“That has been the goal and the biggest challenge,” Bodin reflected, “because students always want to go back to what they know and what they love, but they really, really, have to work to keep other people’s needs at the front of their mind.”

He continued, “If we can teach them and give them experiences where empathy is so valued, then they’re gonna absorb it. They’re gonna start using it in their daily lives. Whether it’s years down the road they realize it, or today they can step forward in empathy, that would be the big goal.”

Greenblatt agreed, stating “Kids everywhere around the world are kids, but they have very different lives and face very different challenges, and for our kids to be able to care about them, and literally put them in their shoes to build that empathy about how someone else feels and the problems someone else is facing, we think that’s gonna make our kids better global citizens for our world.”

And it isn’t just the students the teachers hoped to impact.

As Greenblatt and Bodin had touched on, Estes Park is a rural community. And while many people come into the town from other countries, it’s much more rare for some community members to step out of the “bubble.”

“It challenges — empathy — to really step up in our community,” he said. “Our particular small community is really segmented. With a lot of different ideas. A lot of great ideas, but again, segmented. So if this can bring our community together under one cause or one purpose, or just get us talking more with people who might be different from ourselves, that would be wonderful.”

Elle Naef is a digital media producer at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at ellenaef@rmpbs.org.

William Peterson is a senior photojournalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach him at williampeterson@rmpbs.org.