Denver housing costs skyrocket while supply lags. What's the fix?

DENVER — Elizabeth Williamsberg once dreamed of a detached house, an acre of land and space for animals to run around.

But as the years went on and housing costs in the Denver metro area continued to increase, Williamsberg continually adjusted her dream: A house with a smaller backyard. A house with no backyard. A townhome.

Even a small condo to call her own sufficed for Williamsberg, so long as she could beat the cycle of skyrocketing rents, having to move each time a lease was up and the crushing weight of knowing a rental was simply making someone else richer, rather than building her own equity.

“As time has gone on, the dream has gotten less and less,” Williamsberg said. “It's not even the American dream of the white picket fence. I don’t care about that anymore, it's just wanting something that I can call my own, and that doesn’t even seem possible now.”

Williamsberg currently lives in Louisville, but after a $200-per-month rent hike for her apartment, she scrambled to find a place she could afford and move into quickly to avoid couch surfing or homelessness. After weeks of searching, Williamsberg found a place in the Denver Technological Center, which is on the opposite side of the metro area from where she built a community in Louisville.

A dying dream

Marilyn, a single mother, recent college graduate and a Denver resident who asked not to have her last name identified to protect the privacy of her child, wants nothing more than to provide a space for her two-year-old to run around, meet other kids and play in the backyard.

“I don’t think I’m asking for much,” Marilyn said. “Two bedrooms and a backyard; that’s all I really want.”

After years of moving every six months to keep up with rent increases at the end of each lease term, Marilyn grew fed up and began saving for a house. By the time her savings crossed the threshold of what many realtors told her was necessary for a down payment, the bidding wars began.

The pattern seemed to repeat itself: Marilyn found a home that suited her needs, she scheduled a showing and before she even had a chance to see it, the house sold for nearly $100,000 over the original asking price.

As a single mother, Marilyn feels the odds are stacked against her.

“I'm competing with so many people who have dual incomes and they just continue to outbid,” Marilyn said. “It's sort of a hellish process that you can't win unless you have $500,000 lying around.”

The latest report from the Denver Metro Association of Realtors shows the median home price in the metro area is $575,000, a 21.5% increase since this time last year.

Tiffany Everett, an Aurora resident who has lived in various parts of Colorado over the last decade, first paid $700 a month for a two-bed, two-bath apartment in Colorado Springs when she moved to the state in 2011. Everett has noticed subtle increases each year, but the rise in rent was dramatic when COVID-19 hit the state in 2020.

“It’s just been impossible,” Everett said. “It feels like there’s no light at the end of the tunnel.”

Everett also uses medical cannabis to help manage her chronic pain, and she one day dreams of growing her medicine from home, though that goal is often impossible as a renter, as many landlords she has found explicitly ban cannabis usage, let alone cannabis growth.

Everett now works three jobs, making more money than she ever has before. That has allowed her to save money for a down payment on a house, but every time she thinks she’s crossed the threshold for affording a home, her dream is crushed. She said she had been repeatedly outbid on home offers, which has killed her morale and made her wonder if staying in Colorado is feasible.

“It just feels like a rat race where nobody wins, and it feels worse than a rat race because you can never get ahead,” Everett said. “I genuinely feel like I’d have to win the lottery in order to be able to buy a house.”

Trying to do the impossible

Despite the income from three jobs, Everett said her financial status feels worse than ever before.

“It’s heartbreaking,” Everett said. “It’s really depressing to know that I make more money than I ever have in my whole life and I'm just barely getting by because rents keep going up.”

Many people attempting to buy a home for the first time feel the task is near-impossible because rents in Colorado have shot up over the last several years, making it difficult to save for a down payment.

The Zumper National Rent Report — which measures housing cost increases across the most popular cities in the United States — estimated Denver is the 20th most-expensive city in the country, right behind Sacramento, California. The report found the average two-bedroom apartment in Denver costs around $2,290 each month, a 14.9% increase since 2020.

“It’s a nasty bidding war out there, and people are just getting outbid,” Everett said. “It’s a lose-lose situation … and I’d have to pick up another job if I had any hope of saving up.”

Everett also recognizes she has a privilege many in her shoes do not: she has received several promotions at work and if an emergency were to come up, she could rely on family members for help.

Without that added income each year and the comfort of knowing a trip to the hospital would not bankrupt her, Everett knows she likely would no longer be able to afford her ever-increasing rent in the Denver area.

“If you’re not getting increases to your income, it’s pretty much impossible to save,” Everett said. “That isn’t feasible for a lot of people.”

The problem and the solution

Between 2010 and 2020, Denver grew by nearly 20%, adding 115,000 residents to the city, with the surrounding counties seeing their own explosive growth, according to the 2020 United States census.

Affordable housing advocates and the city's planning staff members say the census data backs up their hypothesis as to why Denver’s housing costs have boomed: too much demand, not enough supply.

You can explore Colorado's 2020 census data below:

- Create and preserve 7,000 homes

- Preserve 950 income-restricted rentals

- Measurably end veteran homelessness

- Reduce unsheltered homelessness by 50%

- Increase the number of people who exit shelter into housing from 30% to 40%, and families from 25% to 50%

- Reduce the average length of time residents experience homelessness to 90 days

- Reduce eviction filings by 25%

- Increase households served in rehousing and supportive housing programs from 1,800 to 3,000

- Help address gentrification with policies that prioritize affordable housing for residents at risk of or who have been involuntarily displaced

- Increase homeownership among low- and moderate-income households, with a focus on households that are Black, Indigenous, and People of Color

- Reduces contract and procurement times

“The biggest thing we need is just more supply, preferably in places where people actually want to live,” said David Pardo, a lead at Yes In My Backyard (YIMBY) Denver, a group that advocates for affordable housing and better public transit. “Adding more dwelling units would mean that our rents wouldn’t keep going up.”

Researchers from the University of Denver’s Daniels College of Business also found Denver had a vacancy rate of just 3.8% in October 2021. The researchers also found Denver has had a $204-per-month rent increase year-over-year since 2020.

Pardo, who lives in the River North Art District and has advocated with Denver City Council for more dense housing in the city, said revamping the city’s zoning codes to allow for more density would solve much of the supply problem. Density, he clarified, doesn’t have to mean high-rises in residential neighborhoods.

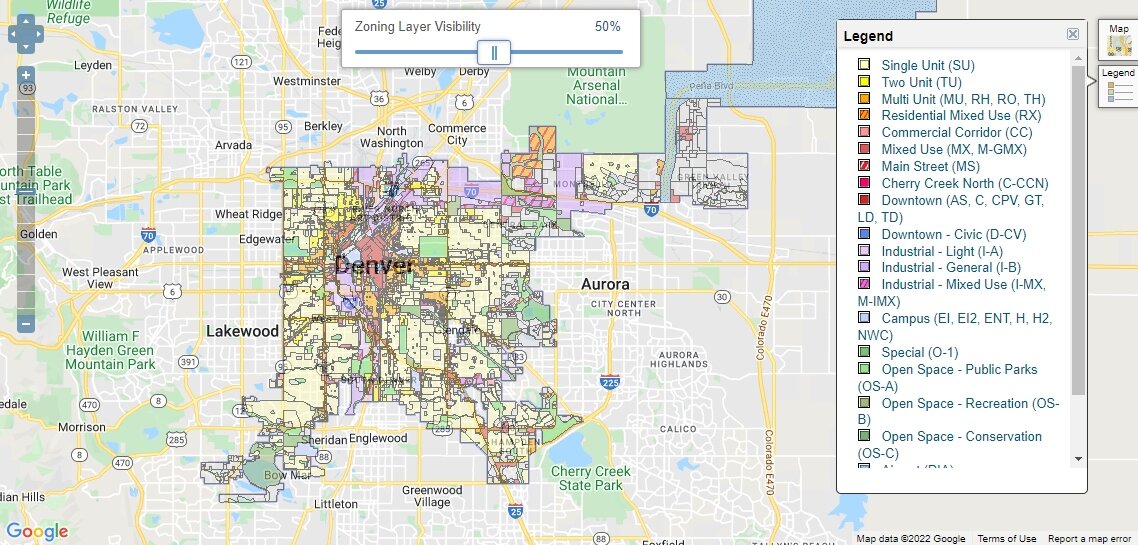

According to a zoning map on the city’s website, much of the land in Denver is zoned for single-unit residencies, which typically means detached houses with individual backyards.

“Most of the city is effectively stuck when it comes to what can be built,” Pardo said. “When I talk to developers, they would love to build townhouses or a few condos, but instead, all they can build are these giant houses that only a few people can afford.”

Pardo pointed to Denver’s Capitol Hill neighborhood as a model the rest of the city could follow, with historic mansions and charming, old houses being modified into multifamily housing units with six to eight condos. This form of density, Pardo added, would ease the housing crisis and create density that fits the neighborhood’s character, as opposed to skyscrapers.

Though the white picket fence and detached backyard may have been the dream decades ago, Pardo said many young people would gladly live in a condo with an individual living space but a shared front yard and hallway.

“Not all of us want a three-bedroom single family home and are going to have two children and want to drive everywhere and need a huge garage,” Pardo said. “It’s those sorts of things in the zoning code that are restricting our housing supply and preventing people from getting the type of housing they want.”

Pardo encouraged people to adopt a “yes in my backyard” mentality, welcoming newcomers with open arms and pushing for the city to build more housing, rather than building a theoretical wall around the Centennial State.

“There are people moving in from out of state,” Pardo said. “But this isn’t their fault; it’s the city government’s fault for not planning for the realities of what this city would become.”

The role of the city

The Denver Department of Housing Stability recently released a five-year strategic plan aiming to put a dent in the city’s housing crisis. The plan envisages “a Denver where race no longer predicts outcomes for involuntary displacement, homelessness, homeownership or cost burden.”

More specifically, the plan intends to accomplish the following:

Britta Fisher, the Department of Housing Stability’s executive director, said the goals came after city officials found that 115,000 city residents are spending more than 30% of their income on housing. More than 48,000 of those residents are spending at least half of their income on housing costs.

“Those pressures really stress all other economic spending on one's budget and life,” Fisher said in an interview with Rocky Mountain PBS. “We really have a vision of a happy, healthy and connected Denver, and in order for that to happen, we need to get people into housing.”

While Fisher said the problem is much more complex than supply and demand, she agreed that the city should revisit its zoning and land-use codes to allow for more density.

“We need housing diversity and a range of housing choices in every community in Colorado, not just Denver,” Fisher said. “There’s a question of what land remains to promote that supply, so we do have to look at land use.”

“Lowercase a” affordable

City planners and affordable housing advocates often use two terms to describe affordable housing. One of them, “lowercase a,” refers to housing that is naturally inexpensive because of its size or location.

As Denver continues to grow, areas that traditionally held “lowercase a” affordable housing have begun to disappear, as units fill up and costs increase across the board.

“If you had a time machine, went back to 2005 and walked down a block in Denver and told people what their houses would be worth today, they would laugh at you,” said Adam Estroff, YIMBY Denver’s president. “But when you see that around you, it feels like everything is kind of out of reach.”

Because almost no first-time buyers can afford Denver’s traditionally expensive neighborhoods, younger people have been pushed into what used to be “lowercase a” affordable neighborhoods.

Gentrification, Pardo and Estroff added, often occurs when people in wealthy areas can no longer afford their neighborhoods. At that point, wealthier people move to lower-income neighborhoods, effectively forcing out those who’ve historically lived in such areas.

“The best way to fix that is to provide housing in the places people want to live,” Pardo said. “Because if you don’t, people have to live somewhere, and people with less money end up on the streets.”

"Capital a" affordable

While “lowercase a” affordable occurs naturally in a free-market housing system, “capital a” housing is built and deed-restricted by city governments as affordable housing.

To put a small dent in Denver’s housing crisis, the Denver Housing Authority recently received $120 million in bond proceeds, with a goal of building 1,300 deed-restricted affordable units by 2024. Haley Jordahl, senior development manager with the Denver Housing Authority, said the $120 million will help expedite the city’s building process.

“We know that growing the supply of affordable housing is critical, because demand is only growing,” Jordahl said. “We’re working to meet rising demands.”

Who ends up in affordable housing is dependent on the housing and the person’s circumstance, but Jordahl said the goal is for no individual or family to be spending more than 30% of their income on housing costs.

Still, advocates believe deed-restricted affordable housing is only a Band-Aid solution for the bigger problem, which is that rents are too expensive for many people, and only a small portion of the population will have access to such housing.

“Rents should be lower for everyone,” Pardo said. “That’s the bottom line.”

Alison Berg is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at alisonberg@rmpbs.org.