How adaptive scuba diving helps people with disabilities do much more than walk

DENVER — Isabella Syvertson’s legs dangled in the warm water, the right and the left appearing to wiggle and wobble in the pool’s rippled surface. Her smile reflected in the water alongside them.

Syvertson had been learning to walk again over the previous months. Now, with a wetsuit on and a tank of compressed air strapped to her back, it was time to soar.

“Getting to be in the water, [there’s] not a worry about anything that’s going to happen to me. It’s a very relaxing feeling to me,” said Syvertson. It’s “...relaxing, calming, and exhilarating, all at the same time.”

Syvertson, a multi-sport athlete who became wheelchair-bound after an equestrian accident, was preparing to scuba dive with a Denver Adaptive Divers (DAD), a scuba diving training program that provides Open Water Diver certifications to individuals with physical disabilities.

The program started about seven years ago when John Sherman, the executive director of DAD, along with four other instructors completed a specialized training to teach and certify disabled divers. Ever since, DAD has taken students across the globe to experience some of the planet’s top diving destinations.

Since the program’s inception, more than 70 adaptive divers have been certified, and upwards of 150 adaptive divers and their able-bodied dive buddies have joined these excursions, according to DAD.

Recently, the DAD began a partnership with Craig Hospital in hopes of spreading awareness about therapeutic diving. Syvertson, who was already in the rehabilitation program at the facility, wanted to dive right in.

Syvertson’s first dip, called the Try Scuba session, allowed her to test the waters in the pool before pursuing full certification.

“I’ve been snorkeling in Mexico, but I’ve never been scuba diving before, so this will be my first,” said Syverston. “And I’m very excited.”

Syvertson (center) learned the gear with the help of two adaptive dive buddies.

Photo: Peter Vo, Rocky Mountain PBS

Beyond the thrill and enjoyment of breathing underwater are the many physical and socio-emotional benefits that come with the sport as well.

“It can reduce a lot of pain, even anxiety, because [patients] have so much movement underwater. Scuba diving can decrease that [anxiety] emotionally,” said Kristi Smith, a recreational therapist at Craig Hospital who has been working with Syvertson.

Craig Hospital has been involved in adaptive diving for decades, and after partnering with Denver Divers, Smith believes more will have the opportunity to get to the water.

“Being out of the chair can be freeing,” said Smith. “It’s an opportunity for people in wheelchairs to feel independent again… to feel more like they used to feel before their injury.”

Research into adaptive diving touts advantages for those suffering from motor dysfunctions, who experience feelings of satisfaction and accomplishment associated with the activity.

One study published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health highlighted that diving gives those with disabilities “a sense of belonging to the elite, doing something unusual, overcoming many obstacles and successfully working to improve [one’s] health status”, that might further encourage individuals to approach other seemingly unattainable goals – such as completing rehabilitation and learning to walk again – with similar attitudes of confidence and determination.

Syvertson has faced the steep, sometimes demoralizing challenges that come with rehabilitation. Since starting Craig Hospital’s TRACK rehabilitation program in December 2023, she has been working with teams of support and training staff and learning how to use a variety of assistive equipment, gradually learning to walk again from the ground-up.

Overlying all of the physical processes was the mental process, a coming to terms with a new lifestyle and the changes she would face even when returning home, she said.

“There were a lot of challenges, especially emotionally, physically. Going through was mainly a huge mental process,” said Syvertson.

Upon first entering the Track Program, Syvertson was asked if there were any specific activities she would be interested in exploring. A lifelong swimmer, she decided that getting back in the pool was a top priority.

Syvertson has had the opportunity to swim a couple of times during her time at Craig Hospital. However, she has noticed a distinct difference in the swimming experience before and after her accident.

As she learns to use her legs again, Syvertson often feels unbalanced, and frequently experiences fears and frustrations with falling. Underwater, she has found that balance is not so much of an issue.

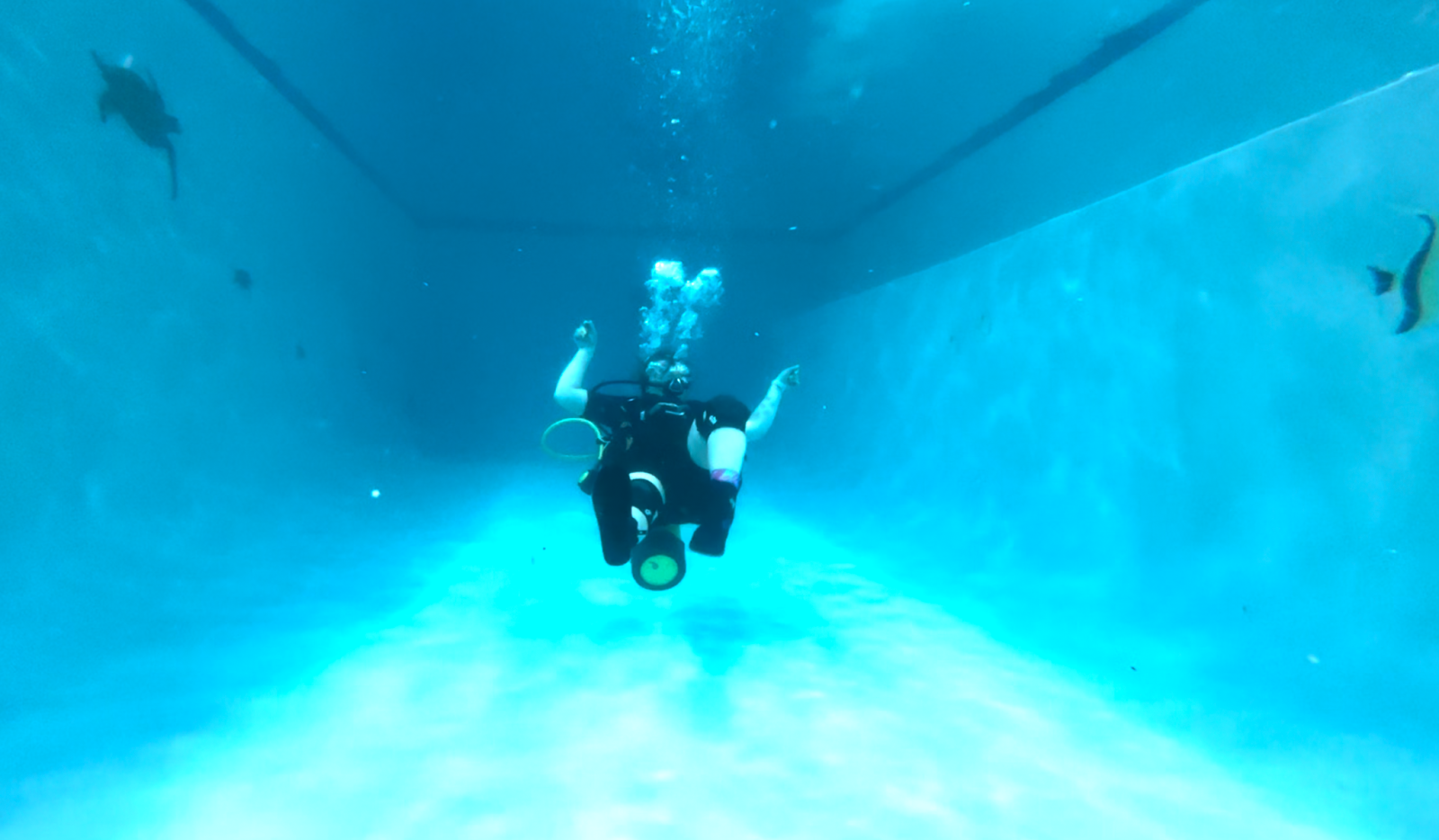

Many able-bodied and disabled divers compare scuba diving to the feeling of floating in space.

Photo: Chase McCleary, Rocky Mountain PBS

“I definitely don't have to worry about what balance I have in the water versus out of the water,” said Syvertson. “I really like being in the water. It calms me.”

Sherman echoed the calming effects of diving, emphasizing that this tranquility extends to the able-bodied as well.

“Regardless of the diver, whether [they] be able-bodied or one living with a disability, the minute their head goes underneath the water… any thoughts about work or stresses or any of that leaves you,” said Sherman. “It’s a sanctuary if you want to think about it that way.”

Sherman, along with dozens of other instructors and adaptive divers, are looking forward to more international excursions coming in the summer.

Syvertson will be completing the final stage of her rehabilitation training at Craig in April. She is looking forward to a highly-anticipated reunion with her dog back home in North Dakota and expects to be back on horseback as soon as she is able.

“I have always been a very active person. My lifestyle is very hectic, very active. So knowing that I would be able to get back to riding my horses was kind of a huge deal for me,” said Syvertson.

Chase McCLeary is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. chasemcleary@rmpbs.org.

Peter Vo is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. petervo@rmpbs.org.