Dearfield once thrived in the plains of Colorado. A new effort plans to bring it back.

DEARFIELD, Colo. — In 1910, Black homesteaders settled into a community on the eastern plains of Weld County they named “Dearfield.” It became one of the few self-sufficient homesteading communities for Black Americans seeking opportunities in the West.

Today, the Dearfield Preservation Committee hopes to turn what remains of the town, which is already on the National Register of Historic Places, into a National Historic Site. Doing so would place Dearfield under the protection of the U.S. Park Service, who would impose tighter preservation regulations and provide more support. The National Register of Historic Places designation, in contrast, is largely honorary.

“To own your own land and to be able to farm it and make money and pass down to your family and so forth, that was an ideal situation,” said George Junne, who is part of the Dearfield Preservation Committee and a professor for Africana Studies at the University of Northern Colorado.

According to the National Park Service, Black settlers of the American West tended to homestead in “colonies” to pool resources between families. After the 1866 Civil Rights Act opened up homesteading to Black Americans, 3,500 claimants succeeded in obtaining titles from the General Land Office, researchers found. All together, Black homesteaders owned roughly 650,000 acres of land across the West.

Roughly 15,000 people lived in these communities, with Dearfield becoming one of the largest. Of the six largest Black homesteads–in Nicodemus, Kansas; Sully County, South Dakota; DeWitty, Nebraska; Empire, Wyoming and Blackdom, New Mexico–only Nicodemus survives as a town.

Although it’s no longer inhabited, Dearfield is the only other Black homestead with buildings that are still standing, according to the National Park Service.

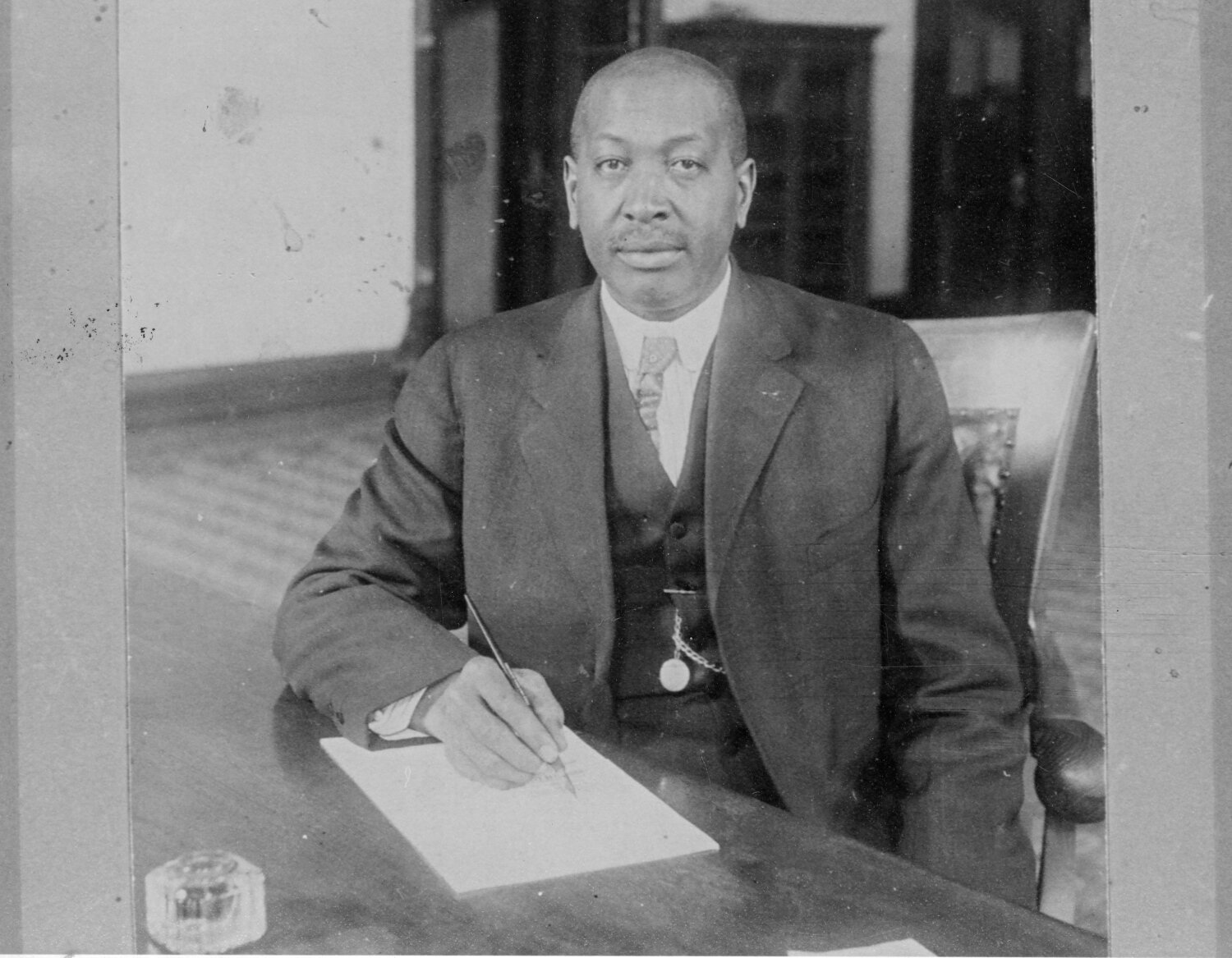

Oliver T. (Toussaint L’Overture) Jackson, a Black entrepreneur born in 1862 to parents who escaped enslavement, founded the town.

O.T. Jackson founded Dearfield.

Photo courtesy the University of Northern Colorado

Jackson promoted land ownership and homesteading to Black Americans, aiming to create wealth and a haven free from racial discrimination and economic hardship. Dr. Joseph H. P. Westbrook, a Black physician in Denver, gave the town its name at an organizational meeting in 1909. He proclaimed that the fields “will be very dear to us,” thus giving Dearfield its name.

In 1921, 15,000 of the community’s 20,000 acreage were used for farming and livestock grazing. Between 1919 and 1923, Dearfield had between 100 and 200 full-time or part-time residents and up to 70 families. According to the Weld County historical record, the town’s net worth that year was appraised at $1,075,000.

“Dearfield was an area where Black people could live and not have to worry about things and settle down,” said Junne.

The Black American West Museum and Heritage Center in Denver today owns 80% of Dearfield and is part of the preservation committee, along with local government, nonprofit organizations and the University of Northern Colorado.

The remaining owners are private families. It is unclear if these owners have any ties to the Dearfield settlers.

The Dearfield Preservation Committee hopes to start working towards rehabilitation and restoration through grants and state funds. The committee has yet to determine the exact cost of the restoration.

“I come from the position of an archeologist and a historian. And I think that the better you understand our past, and [when] I say ‘our,’ I mean all of our past, the better the future will be,” said Bob Brunswig, another member of the preservation committee and a retired University of Northern Colorado archeology professor.

One of the leading restoration goals is stabilizing Jackson’s home, which is located in the heart of downtown Dearfield, with additional plans to turn the “Filling Station,” the only gas station in town, into a visitor center.

Cleaning out his home in 2022, Richard Borys, a Greeley antiques dealer, came across his wife’s history collection containing five ledger books detailing Dearfield’s expenses and private loans, all written by Jackson in pencil.

Borys knew about Jackson’s significance to Dearfield and subsequently donated the ledgers to the Greeley History Museum.

Photo courtesy the University of Northern Colorado.

“The beauty of this project is that things literally turn up out of the woodwork,” said Chris Bowles, manager of the City of Greeley Museum.

Jackson chronicled his life expenditures and business activities in the ledgers. These included his management of the Chautauqua Hotel in Boulder in 1898 and his various loans to Dearfield residents who didn’t have enough money to put down on their homesteads.

In 1910, the Dearfield lots cost between $10 to $25, which would equal $788 in 2024, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Other details from the ledgers include which townsfolk used the one phone in Dearfield, who they were contacting and how many times they called.

There were also letters preserved in the ledgers. One was from a woman in the 1920s who took up work at a farm in Roggen, Colorado. In the letter, the woman wrote she believed that her letters were being read by the farmer and others.

She finished her correspondence with, “I don’t mind work, but I hate slavery.” The word “hate” was underlined three times.

Bowles said he doesn’t believe many documents countrywide detail a Black colony of the early 20th century in such detail.

Despite its success, Dearfield became a ghost town after the Dust Bowl– severe dust storms that significantly damaged agricultural ecology–and the Great Depression. The combined disasters devastated the town’s finances.

“I am really moved by the scale of what [O.T. Jackson] was trying to achieve, and he was very nearly successful if it wasn’t for the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression,” said Bowles.

The Dust Bowl decimated the high plains, making Dearfield no longer viable as an agricultural community. Residents started moving out during the Great Depression, and by 1940, only two homesteaders remained. Many houses, which widely lacked foundations, were sold or collapsed.

“[Homes were] built pretty much on the ground,” Junne said. “They had maybe some bricks and [other materials] under them.”

Junne said Jackson remained undeterred and was starting a new phase to rebuild his town. He hired a man to start plowing fields, but, while the man was working, documents show a plow went through his chest and killed him.

Jackson finally gave up on Dearfield after the man of hire’s death.

“O.T. Jackson lived in [Dearfield] as long as he could,” said Junne.

Jackson stayed in Dearfield until 1942, when his wife died, and moved to Greeley once his health became too poor, Junne said.

The founder died in Greeley in 1948 and was buried at the Linn Grove Cemetery.

“The more that we become acquainted with Dearfield’s past and all of these varied ways that we’re trying to understand it,” said Brunswig. “It’s telling the story of people who lived such interesting and challenging lives.”

Volunteers behind the preservation push hope to have an official answer about Dearfield’s National Historic Site protections by 2025.

Lindsey Ford is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. Lindseyford@rmpbs.org