Unexpected path led Colorado woman to serve

COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. - City Council Member Yolanda Avila says she had three strikes against her when she decided to run for local office: “being a woman, being Mexican-American, and being blind.”

Though each, she said, provides its own obstacles, “I wouldn’t trade it for anything. The challenge, and working through it — the reward is even bigger at the other end.”

This reward has been tangible for Avila and her constituents, who live in southeast Colorado Springs in what she calls “overlooked” neighborhoods. Avila has fought for local infrastructure improvements, increases in accessibility, and more robust public transportation.

“I have such a sense of purpose serving the Colorado Springs community and my district,” she said. “Things have been moving forward for us, and I’m so grateful. There’s truly no place I’d rather be.”

Yet it’s not what she expected.

Avila was diagnosed in 1998 with retinitis pigmentosa.

“I was told the prognosis was complete blindness. I kind of lost it,” said Avila in an interview in Council chambers with Rocky Mountain PBS. “I was thinking, what am I going to do? What can a blind person do? All I could see was a loss.”

Yolanda was working as a criminal defense investigator in Orange County, Calif., when she received her health news.

“It was the job of my dreams. I was so happy,” said Avila. “I could not wait to go to work in the morning. And I was getting promoted. I was moving up.”

For several years, Avila struggled as her vision deteriorated. She feared her boss’s reaction to her condition, and that she’d lose her occupation — her livelihood. What’s more, her job offered a direct connection to public service — and her sense of connection to her community.

When she told her boss she was losing her eyesight, her workplace was beyond supportive, Avila said. They supported a role change, helping shift her dreams instead of letting them all go. Avila adapted from working predominantly in the field as an investigator to a more internal role. She soon found an aligned passion in helping reunite children with deported parents.

“When the parents were deported, their parental rights were being immediately terminated,” said Avila. “More and more kids were ending up in the system.” She combined her own skills with the Mexican consulate, social workers, and attorneys to make a plan for parents to reunite with their children and bring them from California to Mexico.

Avila was relentless in pursuing rights for unification. When she began, she said, 80% of the parents deported back to Mexico permanently lost rights to their children. By the time she left, that statistic was flipped, with 80% reunited with their parents.

“That is the best work I ever did,” said Avila.

The work was close to her heart.

Her father, born and raised in Garden City, Kansas, was one of 14 children, and working class. Her mother was born and raised in Ario de Rosales, Michoacán, one of eight children, and wealthy.

In 1933, when her father was 18, America reinstated “Mexican round-ups,” Avila said, deporting not just immigrant workers, but also American citizens with Mexican heritage. “And so my dad, the youngest kids, and my grandparents were deported from Kansas to Mexico — even though they were all American citizens.”

Her father had just graduated high school. He found himself “sent back” to a place he’d never lived. Now a resident of Mexico, he attended a teacher’s college with the hopes of working in education. There, he met Avila’s mother.

And in 1944, more than a decade later, her father got a a different letter from the United States — a draft notice. He was now being required to serve in World War II. Seeing it as a chance for opportunity, he answered the call, bringing his wife and eldest two children back to Garden City, Kansas.

“My dad was drafted into the Army,” said Avila. “He went to serve in World War II and on to serve in the Korean War.”

Not only did Avila never know her father had been deported before she was born — it was a family secret she stumbled upon by chance.

“I was attending Colorado College studying U.S.-Mexico relations. I was reading about the deportations and the round ups that happened during the Depression. I went to go visit my parents that night, and I said, ‘Hey, did you know they deported American citizens that were Mexican Americans?’ And my dad got this really serious look on his face. And my mom looked at me and said, ‘De digo despues.’” Which means, “I’ll tell you later.”

“Nobody knew,” she said. “I think it was important for him to prove that he was American. He was born and raised here.”

Avila came to Colorado Springs at the age of three in 1958 when her father was stationed in Fort Carson. Seeing the mountain peak, her mother was reminded of her childhood home in Mexico. “She told my father, “This is where I want to live,” said Avila.

“I truly grew up in a bilingual household. My dad didn’t want us to have an accent, so he only spoke English to us. And my mother only spoke Spanish to us,” Avila said.

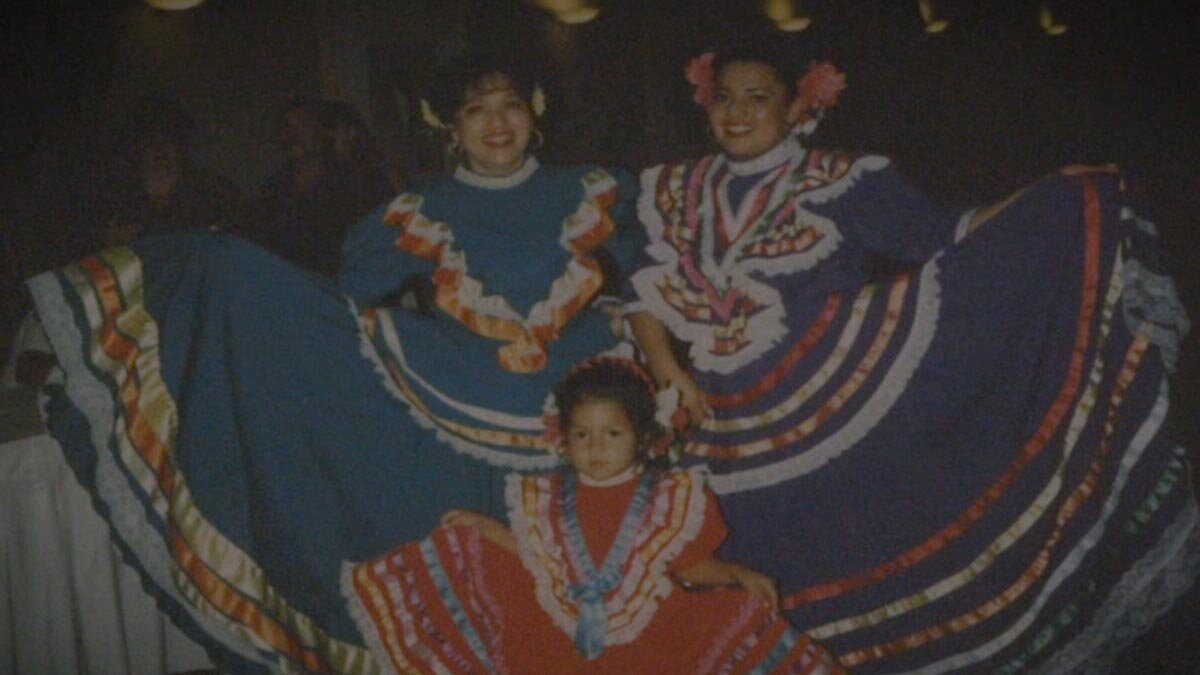

Her mother got involved in the Colorado Springs community, helping to organize festivals and strengthen the local Latino scene. Her mother taught traditional dance, and Avila grew up performing throughout Colorado Springs.

Her elementary, middle, and high school years, she said, “were tough. The students would tell me to go back to where I came from,” she said.

When visiting Mexico, her mother’s family laughed at her Spanish, calling her “gringa.” “You’re not one of us,” was the message.

“Growing up in America, it’s like I wasn’t American, but in Mexico, I wasn’t Mexican. It was tough.”

Eventually, Avila came to understand how unique and inspiring her multi-faceted heritage is. “I am both American and Mexican, and I’m going to take the best of both worlds and combine them,” she said. “I became very proud of being Mexican-American, whereas before I was kind of ashamed and felt I didn’t belong.”

It’s no surprise why Avila may have felt that way. As Mexican Americans growing up in Kansas, her family could not swim in the swimming pool until the day before they changed the water. Discrimination was everywhere.

“Half of my family is lighter complected, green eyed, and the other part is really dark.,” said Avila. “In the theater, they would break up the family. The darker ones had to sit in the balcony, and the lighter complected kids could sit in the orchestra seats.”

This was hard for her mother to bear.

“She refused to be treated less than,” said Avila.

After retiring in 2011, Avila returned to Colorado Springs to be near her mother.

Her homecoming was bittersweet. Though she’d missed home, Avila noticed a stark contrast between the crosswalks and public transportation of California, and the five-days-a-week, limited bus schedule of Colorado Springs. In short, she could no longer rely on public transportation.

“The nearest public bus stop to my house is over a mile away, and inaccessible,” said Avila. “If I call the local mobility service, I wait about forty minutes. I have to justify why I need a ride. I think, ‘If I’m going through this, and I am capable, and I am who I am… then other people must really be struggling.’”

Almost inherently, Avila became a passionate voice for public transportation accessibility. Together with a coalition, relentless education, and petitions, she helped overhaul the curb and crosswalk protocol of Colorado Springs. The buses went from running five days a week, to seven.

When the City responded to the transit needs, “I though, wow, that’s really something,” said Avila. “We really made something happen. And I thought, if I were to run for office, I would have an even bigger voice for improving transit.”

Avila ran for an At-Large Council seat in 2015. She says she didn’t know much about campaigns, and had difficulty filling out all the requests for platform information from public interest groups and organizations. It was frustrating, she said, to participate in forums and media requests, which were also not always accessible. And to get there, she was often taking public transportation with her companion service dog Puma. “I was completely out of my realm,” she said. “Once, when I got off the bus and got home, I cried. I thought, ‘How am I going to do this?’”

Friends, family, and the community encouraged her to continue — despite having no campaign manager.

Avila persisted.

“I said to myself, ‘Yolanda, you have to let people know that you’re just as capable. It’s just going to look a little different,’” she said.

Avila lost the first election. She began preparing to run for her District seat in 2017.

This time, Avila won.

As a Council Member, Avila continues to take on change in improving public transit accessibility and routes, and addressing food deserts, health, and homelessness. Fellow Councilors, she said, can be less than empathetic.

“With a lot of these things, if they haven’t been in that situation, they just don’t understand,” Avila said. “Like how they will only go so far with plans for transit — because many have never even been on a city bus. They just don’t know what it’s like.”

She says she sees the issues as reflecting leadership’s priorities — and it’s not about funding.

“The resources are there,” Avila said. “It’s not about money. And people in my district don’t even ask, because they don’t feel as valued. They don’t know that they deserve everything that the rest of the city has.”

Avila is committed to making sure her community knows their value. She aspires to listen deeply with resolution and focus.

“Ever since I was little, I could feel the energy in the room,” said Avila. “What I’ve learned is, sometimes people’s sight is a distraction. They’re looking at everything around them, and not listening to what’s going on. I am truly listening.”

Avila has been welcomed as a leader by the Colorado Springs community, providing a hopeful, vibrant, and experiential perspective on Council. In 2020, the Colorado Springs Women’s Foundation and Pikes Peak Women honored Avila’s contributions with an event in her honor. Avila was also named a 2020 Colorado Springs Woman of Influence.

“One has to speak out. Speak up, suit up, show up,” said Avila. “You might think that what you’re doing isn’t important. It is. It is so important, whatever it is. I encourage people to step into their own power. If there’s anything I can do to support any woman who wants to run for office, please give me a call.”

And never feel limited by an unanticipated path.

“I don’t think I would be here if everything had turned out as I had planned,” Avila said. “I think being back in Colorado Springs is a calling. And I couldn’t be happier.”