Colorado workers now have paid family and medical leave. Here’s what you need to know

DENVER — When Kris Garcia spun out on black ice on I-25 last year and careened into a concrete barrier, he suffered internal bleeding and a knee laceration that penetrated all the way to the bone.

He had to be on leave for three months from his job as a ramp lead with United Airlines – a job that required him to be on his feet all day on the tarmac at Denver International Airport. Because the injury happened outside of work, Garcia wasn’t paid for the time he needed to take off.

Garcia is his family’s breadwinner, and he says it took nine months for his family to recover financially from the mounting mortgage payments, car payments and medical bills that piled up.

“It's hard to get caught up when you’ve got late fees on late fees,” Garcia said. “When you’re thinking about a person’s well-being, the last thing that should be necessary is to sit there worrying about how you will make your next payment.”

Now, Colorado workers will no longer have to worry about that.

This January, Colorado inaugurated a new social insurance program called Family and Medical Leave Insurance (FAMLI). Workers in the state are now eligible for up to twelve weeks of paid leave per year to bond with a new child (including adopted and fostered children), care for themselves or a family member’s health condition, make arrangements for an upcoming military deployment, or address safety needs following sexual assault or domestic violence.

Most workers who’ve made $2,500 in a year are eligible to apply – including self-employed and freelance workers.

Over the last year, employers and employees in Colorado have paid into the FAMLI program. The premiums are set to 0.9% of the employee’s wage, with 0.45% paid by the employer and 0.45% paid by the employee.

Nearly every Colorado employer is required to comply with the FAMLI Act's requirements – by either participating in the state program or providing a private plan of equal or greater benefit.

According to Colorado’s Department of Labor and Employment, only about 3% of private businesses have chosen not to participate in the program, and are instead offering a similar program through a private plan carrier.

Only local governments, federal employers and some railroad employers are exempt from having to participate in the program.

Colorado joins at least 10 other states with paid family and medical leave laws, including California, Connecticut, Massachusetts and Washington.

Colorado was the first state in the country to pass the law by ballot initiative, Prop 118, which voters approved in November 2020 after similar bills stalled for years in the state legislature.

Family and medical leave isn’t new – the national Family and Medical Leave Act, which took effect in 1993, grants 12 weeks of job protected leave for most employees. But it’s unpaid leave and excludes many part-time workers, workers at small-sized businesses and those who have worked less than 12 months.

“We just don't have a comprehensive solution in this country for allowing people to take time off from work with pay,” said Kathy White, executive director of the Colorado Fiscal Institute.

“There are a lot of people who do have good benefits through their employers, but you shouldn't have to win the employer lottery in order to have this really critical economic security benefit,” White said.

According to a survey conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 24% of private-industry employees across the country had access to paid family leave through their employers in March of 2022, and 43% had access to employer-supported short-term disability insurance policies.

The benefits were most prevalent for full-time workers in high-paying occupations, employed by large companies.

“Low-income workers who have faced lots of barriers just don't have this benefit through their private employers and their earnings are too low to not be paid while they're on leave,” White said.

White and the Colorado Fiscal Institute have been advocating for paid leave in Colorado since 2013. Over the years, other community organizations such as 9to5 Colorado and Good Business Colorado have also supported it.

“The failure of the federal government to come up with a federal and national solution – that would really be the easiest thing, the best thing, the most cost- effective thing. It would be the easiest for compliance purposes, but they just haven't done it. And so I think states are really looking to take the lead,” she said.

Compared to other wealthy countries, the U.S. is alone in its lack of a nationwide paid leave program. All 38 countries in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) offer paid maternity leave except the U.S. – with Greece offering the most leave at 43 weeks.

As of February 12, the FAMLI office had received more than 22,000 claims, approved 12,500 claims and paid out about $37 million.

“The vast majority of claims at this point have been for bonding with a new child,” said Tracy Marshall, division director of Colorado’s FAMLI program. She said her office has brought on nearly 300 staff and set up two call centers to manage the claims.

“It's a very, very large behind the scenes operation and it's been rolled out quickly. November 2020 wasn’t that long ago,” Marshall said.

“To build a start-up within a government agency in three years that is fully functional and serving the public is a really strong feat from the Department of Labor," she said.

The FAMLI measure had the support of 57% of voters in November 2020. Colorado became the first and only state to pass a paid leave program at the ballot box that year.

Photo Courtesy: Colorado Family and Medical Leave Insurance Program (FAMLI)

For small business owners like Katharine Knarreborg, who runs a three-person engineering and manufacturing company, the FAMLI program alleviates the administrative burden that she would otherwise have had to provide.

“I don't want to have to review doctors’ notes to determine: Is this really a disability? I don't have an HR department to do that,” Knarreborg said.

Under FAMLI, workers file claims directly with Colorado and the state manages every aspect of the program.

Knarreborg said she long wanted to offer her employees paid family and medical leave, but couldn’t find an insurance company willing to offer it.

“When I was trying to look on the private market for insurance products, it was very hard to find any broker willing to offer insurance to a business of my size,” she said.

Knarreborg offered paid leave to her employees on an ad-hoc, case-by case basis over the years, but said for some employees, it could warrant an awkward conversation.

“Employees are nervous that maybe if they ask for too much, they will lose their job,” she said. “I think having a program that exists and has some clear guidelines and expectations allows employees and employers to work together.”

Knarreborg was able to provide short term disability insurance for the past five years – but for new parents, it only included four weeks of paid maternity leave.

The cost of FAMLI is about the same as short-term disability, she says, but “my employees get much better coverage and much better time off.”

Despite the program’s promises, some worry it will become too expensive to support. Chris Brown, vice president of policy and research at the Common Sense Institute, said the biggest problem is that the program guarantees benefits, regardless of the program’s financial state.

“If it's a very popular program, then that becomes its own sort of financial undoing. And like any insurance plan, the premium has to support the claim,” Brown said. “There should be a mechanism to moderate those benefits in the event the funds available are not sufficient.”

While the premiums paid into the program currently stands at 0.9% of an employee’s wage, it can rise to a maximum of 1.2% if the program needs more money. Beyond that, funds would have to come from somewhere else, for example, the state’s general fund or taxpayer dollars.

“Other states that have passed these paid leave reforms have put in rules that say: ‘Look, if the cost rises above X, then we will begin to moderate the benefits. So instead of offering, say, 12 weeks, we would offer 11 weeks,” Brown said. “This way you can control the costs.”

Connecticut is one of the states that built in a mechanism to adjust benefits to prevent insolvency.

Washington state’s paid family and medical leave program recently faced significant budgetary shortcomings. The state had to raise the payroll premium twice between 2021 and 2023, and lawmakers set aside $350 million of the state budget to address potential deficits.

Brown noted other potential challenges: “This is a one size fits all model.” Businesses with a lot of shift-related work – like hospitals and restaurants – may struggle to find trained replacements on short notice when employees take leave, he said.

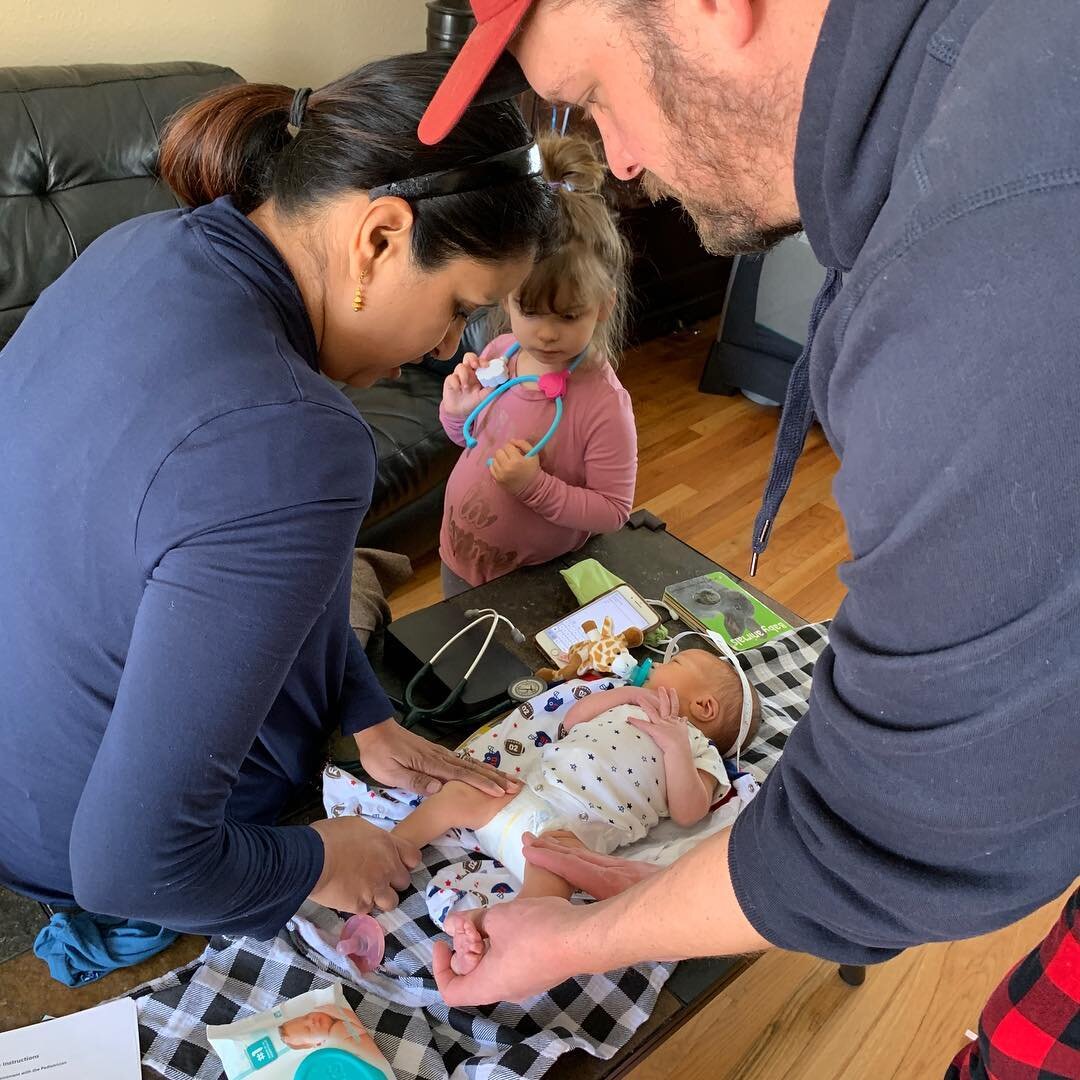

Caption: Dr. Sonal Patel conducts home visits with new parents. Patel, who testified in support of FAMLI with Good Business Colorado and 9to5, said lack of access to paid family leave affects new parents in all socioeconomic classes, irrespective of income.

Photo Courtesy: Dr. Sonal Patel

Dr. Sonal Patel, a pediatrician and neonatologist in the Denver-Golden area, said a paid family leave program is crucial for the health of new parents and the development of babies.

“Countries who invest in paid family leave have a reduction in health care costs,” Patel said. “Those mothers are able to breastfeed longer, have less postpartum depression and have less outcomes related to having an infection.”

Patel’s book, “The Doctor and Her Black Bag,” details some of these findings and argues a new system is needed in the U.S. to reduce maternal mortality rates.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, Patel said she’s seen a lot of new mothers turn to telework in the absence of strong paid family leave policies.

“Some women think: I’ll just go back to work and work on my computer,” she said. “But there's no space to actually recover from what they’ve gone through.”

And working from home shortly after giving birth can limit the amount of time a parent has to bond with their new child.

“A lack of bonding actually results in poor infant development, so [babies] don't meet their milestones in time, and they're not ready for school,” Patel said

Eventually, that lack of development can affect that child’s mental health into adolescence, she said.

Kathy White hopes Colorado’s new leave program will become a model for other states.

“It’s a humane way to treat our people and our workers,” White said.

“I hope we have to work a lot harder to find stories of people who say, ‘I had to talk to my father on the phone from my break room in Colorado while he was dying by himself in a hospital bed in Texas.’ Or people who say, ‘I had a baby and I had to go back to work two weeks after giving birth.’”

To apply for FAMLI or to learn more about the program, visit https://famli.colorado.gov/individuals-and-families/my-famli

Andrea Kramar is the investigative multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. Andreakramar@rmpbs.org