For grandson of Camp Amache incarceree, historic designation 'creates permanence'

LOUISVILLE, Colo. — In a neighborhood where families consider themselves incredibly lucky if their family homes and memories were saved, Calvin Taro Hada is grateful another part of his family’s story and the history of thousands of others will soon be permanently preserved.

Hada lives in Louisville in the same home he and his family have lived in for more than two decades. He, like many families around him, recently had to evacuate his home when the quick-spreading Marshall Fire ripped through Boulder County on Dec. 30, 2021. Luckily, Hada's home was spared, despite the fire reaching within a few blocks of his neighborhood.

Now, his story is not just about what was saved in his home, but what will soon be permanently saved in the small southwestern town of Granada, Colorado.

“You know, it came so fast. I still haven't caught my breath,” said Hada about the Amache National Historic Site Act, a bill which he has been a strong advocate for. It recently passed the Senate and House of Representatives in Congress and is waiting for President Joe Biden’s signature. The act adds the Granada Relocation Center, a Japanese internment camp commonly referred to as Camp Amache, to the National Park System.

“Primarily, it creates permanence,” explained Hada. “So for me, it's almost a vindication for my love of country. I think that every time something like that happens, it tells me that my love of country is justified."

Camp Amache was one of 10 internment camps — or, as Hada called them, “concentration camps” — established after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Executive Order 9066 from President Franklin D. Roosevelt created a military zone along the coast of California, Oregon and Washington in which he gave the army the authority to remove anyone that they felt might be a threat — this included more than 120,000 Japanese-Americans.

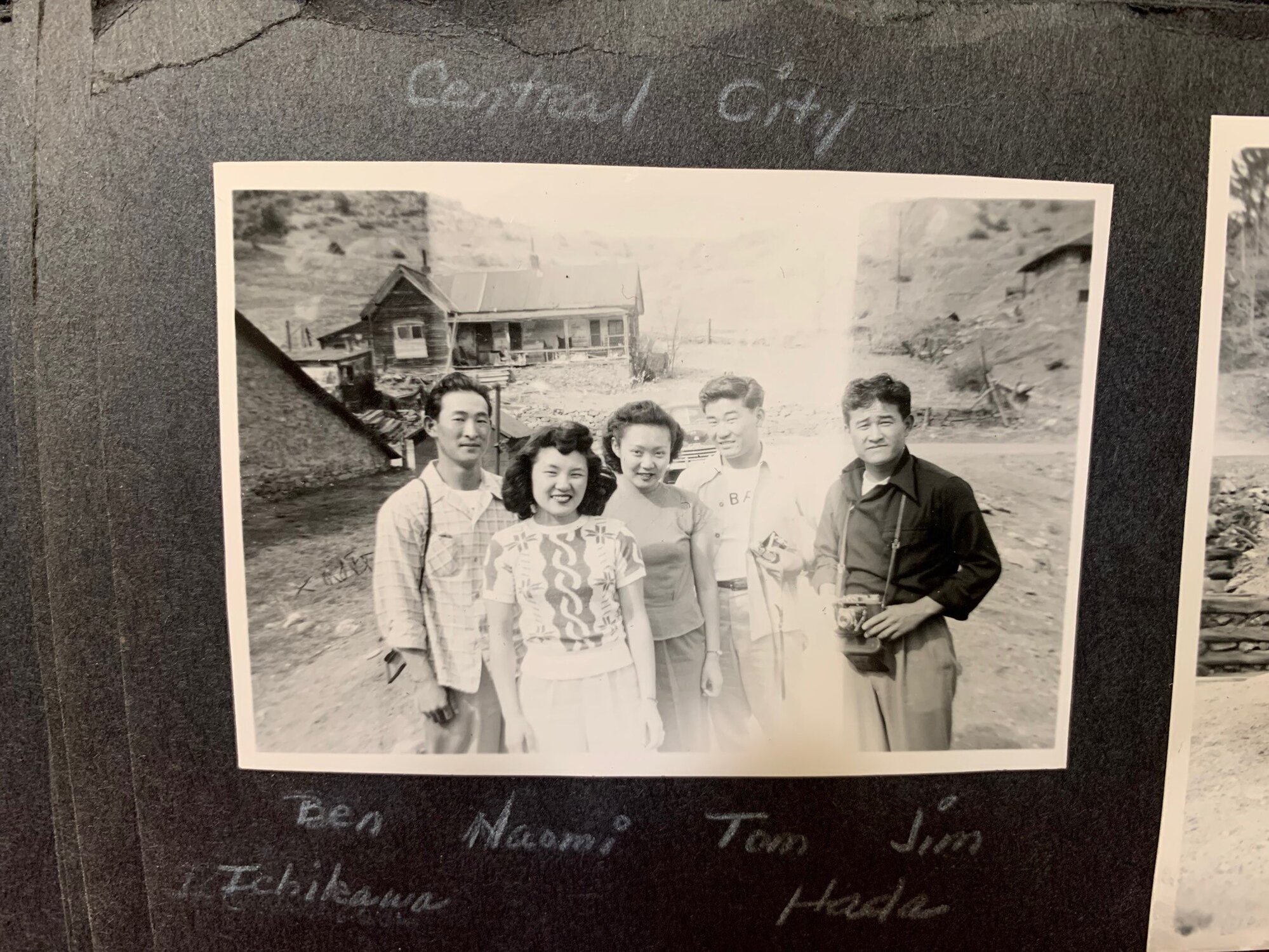

Camp Amache held nearly 8,000 internees, including Hada’s paternal grandmother, Hama Serizawa.

Hada’s grandfather, father and his siblings were living in Fort Lupton at the time of Executive Order 9066. But he said his grandmother had stayed behind in California to look after a family-owned boarding house, and American troops took her into custody and transferred her to Camp Amache.

Hada’s father, James, decided to join the army after the United States entered World War II and went to say goodbye to his mother at Camp Amache before he was deployed to Germany, unsure if he would return.

“The guard at the gate wouldn't let him in, even though he was wearing his Army green uniform,” Hada explained. “So he had to make his goodbyes to his mother through the barbed-wire fence.”

James Hada went off to war to fight for his country, the same one that imprisoned his mother. When the war was over, James returned to Colorado, but his mother was so hurt by the internment that she moved back to Japan.

“It's very hard on my dad and his siblings. I know that they met her a few times before she left. And when she returned to Japan, we had no idea what happened to her. That was a terrible place to be after World War II … So I often wonder about her,” said Hada.

However, Hada didn’t learn about his grandmother’s internment in Granada, or even about Camp Amache itself, until he was a teenager. Growing up in the 50s and 60s, Hada’s parents wanted to raise him and his brother like “any American kid,” he explained.

“I had very little understanding of my racial heritage or culture or anything like that. My parents just wanted to have ‘Leave It To Beaver’ basically. And I didn't know any different until I was about 14,” said Hada.

That is when his dad gave him a book about the internment of Japanese-Americans in World War II. After reading about it, his immediate reaction was anger.

“I couldn't believe that it was done to my family by my country,” said Hada. “So that began me on a decades-long journey of trying to discover my Japanese roots.”

Now, Hada is involved in several Japanese-American community organizations. For the last 12 years, he has served as president of Nikkeijin Kai of Colorado, which was formed in 1907, making it the oldest Japanese-American organization in Colorado.

“We don't have a big percentage of Colorado that are Japanese-American, but we're pretty tightly knit,” Hada said. “I do quite a few other things in the Japanese-American community [which] have been done primarily so I can fill in the void of my understanding of my heritage.”

James "Jim" Hada, passed away in March 2016 at 91 years old. He spent a significant amount of his life advocating for the Japanese-American community, serving as president of Nikkeijin Kai of Colorado before his son. And all of James’ work to help build cultural bridges between Japan and the United States earned him the Kunsho-Order of the Rising Sun with Gold and Silver Rays award. It is the highest honor a non-citizen of Japan can receive from Japan, an award that Hada learned he will be receiving too.

Related Stories

Hada has visited the site several times, as the Nikkeijin Kai of Colorado takes an annual pilgrimage there in May. The trips are just one part of Hada's ongoing reconciliation with the pain of hundreds of thousands of Japanese-Americans and his identity as an American.

“It created a dissonance with my love for country,” Hada explained. “So it was hard to balance the two together. And I don't know if there is a way to do that, but I think the passage of the Amache National Historic Site Act is a good step towards that."

Amanda Horvath is a multimedia producer with Rocky Mountain PBS. You can email her at amandahorvath@rmpbs.org.

Alexis Kikoen is a senior producer at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at alexiskikoen@rmpbs.org.

Today I had the honor to visit the Amache Historical Site, a former Japanese American incarceration site in Colorado. I am grateful to the survivors and descendants of Amache who share their stories to help us all learn about this painful chapter in our nation's history. pic.twitter.com/azFoMZXyLv

— Secretary Deb Haaland (@SecDebHaaland) February 20, 2022

Honored to welcome my good friend @SecDebHaaland to Colorado as we remember lives touched by Japanese internment.

— Rep. Joe Neguse (@RepJoeNeguse) February 20, 2022

Our effort to safeguard the Amache Site will encourage healing and honor for those who lived through this dark time in our nation's history. pic.twitter.com/yvMNRjvbq8

Today marks the 80th anniversary of the executive order that forced the incarceration of 120,000 Japanese Americans at facilities like Amache in Colorado during WWII.

— Michael Bennet (@SenatorBennet) February 20, 2022

I joined @SecDebHaaland along with Amache survivors and descendants at the site to mark this solemn anniversary. pic.twitter.com/T3sd1UxuBF

“I was frankly stunned,” he said about his feelings when he first heard he would be receiving the honor too. He explained other people who have won this award include Kimiko Side, a woman he called the “matriarch of the Colorado Japanese American community.” He said she’s donated thousands of dollars and tons of time to the Buddhist Temple and to Simpson Methodist Church, both of which are Japanese-American churches.

“That's the kind of person that I think of when I think of the Kunsho. And so I guess I received the award because I was the president for 12 years, but I have worked hard to create understanding between Japanese-Americans and other Americans,” said Hada.

Advocating for the Amache National Historic Site act is part of that work for him. Hada said he hears from people of all ages who don’t know about Camp Amache and the internment of the Japanese-American people and believes it's important to preserve and educate people so we, as a country, don’t repeat our mistakes.

“I think it's a constant struggle to combat racism," Hada said. "We have to keep up the struggle, and seeing the repercussions of something like this to an identifiable minority, like the Japanese-Americans, has to be a sobering thought to all Americans who believe in the constitution."

While this internment happened 80 years ago, Hada said the idea of imprisoning a certain group of people has also been a more recent fear. He recalled that after the September 11, 2001 attacks, he met with leaders of the Arab and Muslim who were terrified.

“They were clearly afraid it was going to happen to them and their families,” said Hada. “And I like to believe that the lessons that we learned about the incarceration of the Japanese Americans help prevent a similar activity against them.”

February 2022 marked a significant moment for history of the internment of Japanese-Americans and Camp Amache itself. The 19th marked 80 years since Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, and this year, President Biden declared the 19th as official Day of Remembrance. Along with the passage of the act to make Camp Amache part of the National Park System, many federal leaders visited Granada to see the site for themselves. That included Secretary of the Interior, Deb Haaland, the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary.

"She knows full well the stories of what has happened to her people and continue to happen to her people. In fact, she made the point that the Wounded Knee National Historic Landmark, the site of the massacre, is only about 400 miles and 80 years apart from the Amache incarceration site," said Hada.

Haaland along with Senator Michael Bennet, Congressman Joe Neguse and others toured Camp Amache Saturday, Feb. 19. The site includes informational kiosks, a museum and several commemorations and cemeteries for those who died and who were interned at the site.