Colorado park ranger reflects on four decades with the National Park Service

MONTROSE COUNTY, Colo. — Handing over your keys on your final day of work after four decades can come with a rush of emotions and feelings. For a National Park Service ranger, handing over those keys means so much more.

“I'm actually turning in the keys to America's heart; that heart has both beauty and wonder held within our hearts, along with the angst and the struggle and the sorrows that we have, that's the sweep of the American story,” said Paul Zaenger, a recently retired Supervisory Park Ranger with Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park.

These are the sorts of statements and revelations you hear from just one conversation with Zaenger. A husband, a father, and a park ranger who has a deep love for this country, its people and even its turbulent past. He plans to continue nourishing that passion for years to come, despite hanging up the gray and green park ranger uniform and flat hat.

His love for the outdoors started at a young age. With YMCA, scouting, or camping with family in Ohio and Michigan, Zaenger found himself outside a lot and dreaming of a job with the National Park Service.

“So what ended up happening was I was out on a date, and this young woman said, ‘Oh, I know a park ranger at a park in Ohio,’” said Zaenger. And he couldn’t believe his luck. Sure enough, he got in touch with the ranger and started what would become a long career at Perry's Victory and International Peace Memorial.

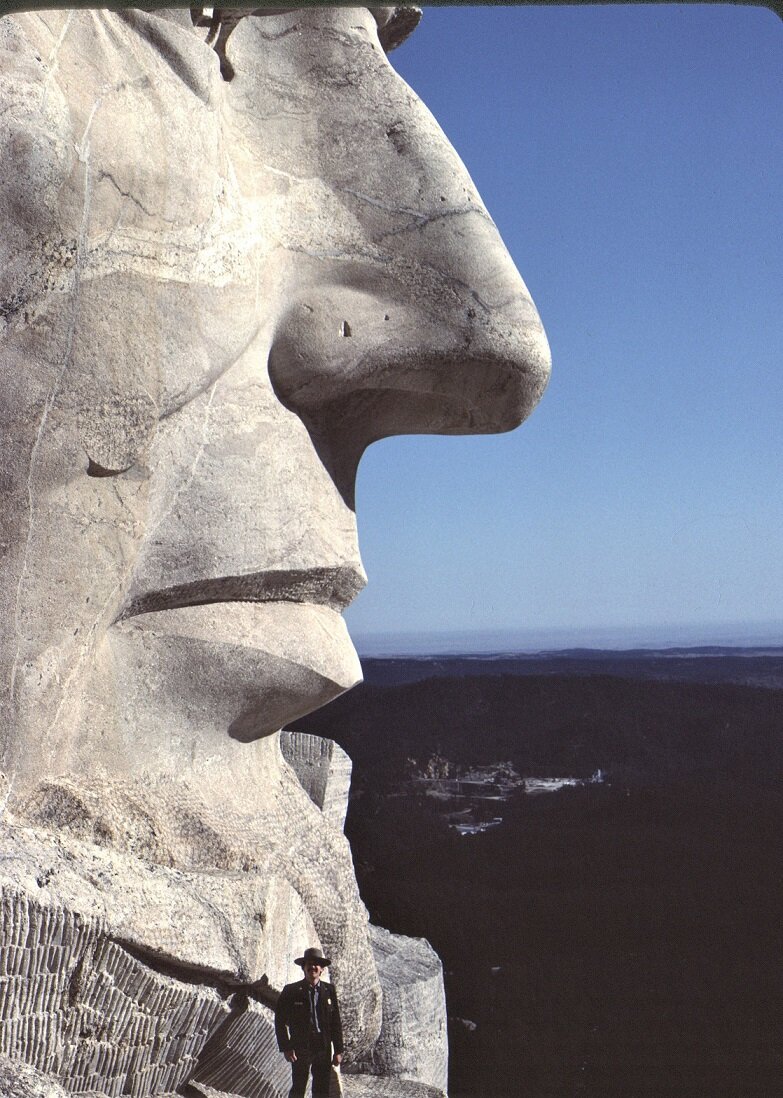

From seasonal and full-time work, he found himself working at some of our country’s most famous landmarks including the Statue of Liberty, Mount Rushmore, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, and Death Valley. Then, Zaenger landed at Black Canyon in 1993 with the title of interpreter, where he stayed for the next 28 years.

“I have been the most visible because I've been involved with interpretation, which is finding a link in language between the stories of the park and the power of that place. And translating that into language that the public can embrace,” explained Zaenger.

And that work has not gone unnoticed. In a social media post about Zaenger’s retirement, Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park wrote how his community building efforts and connections helped lead to successes like achieving national park status in 1999, and how “he has shaped the careers of countless rangers and interpretive programs around the Service.”

From creating outdoor panels to helping make a movie shown in the visitor center, Zaenger has had his hands in a lot of projects. The list could go on and on, or as he puts it, "blah, blah, blah." But those numerous projects are not what he sees as the most valuable part of his time as a park ranger.

“The most important thing, though, with all of that work is that interface between ranger and the place. Whether that's geologic places in the case of Black Canyon maybe ... maybe the big trees at Sequoia National Park, the Saguaros... in Southern Arizona,” explains Zaenger. “It's that interface between ranger and the public and that place. The public can be really engaged in our heritage and in these places. And that's what makes it really worthwhile.”

That special connection between place and the people is something Zaenger continued to emphasize and protect during his time as a ranger. He said that often, national parks can be a place of great wonder and reflection for people. Rangers can act as those patient listeners people sometimes find in religious leaders, hairdressers or bartenders.

“There is this honesty that is there; the honesty of mistakes that we've made, as well as the triumphs and the successes that we've had,” said Zaenger. “Sometimes visitors talk to us in uniform with a lower guard; they share things that maybe you're probably not going to share anywhere else.”

Those immensely impactful moments often happen at places like Black Canyon. With the Gunnison River spending thousands of years carving through the rock, looking down the cliff sides can take your breath away—something that never really gets old, even for a longtime park ranger who speaks of his relationship with the park like one with a romantic partner.

“I have had the benefit of being at Black Canyon for a very long time, 28 years,” explained Zaenger. “And so that doesn't mean that the thrill of being with Black Canyon has diminished, but that the relationship in that love of the places is kind of grown and changed and altered and evolved."

He continued to describe some of the power behind that relationship:

“So that when I'm out there in a false storm, where the clouds hang low over the rim of the canyon, or they actually rise and fall, and those mists rise and fall and wrap around the columns and the towers and the pinnacles that are out in the canyon, or up against some of the big cliff faces like Wild Bill's Wall or the Painted Wall that...it's an enriching experience. It's enriching my relationship. And when rangers have that, it really brings out a greater public service that we can connect people to the power that exists in all of these places.”

The power of a place like Black Canyon also comes at night. The park, which is also the Colorado's least-visited national park, is part of the International Dark Sky Places Program, an organization that encourages communities, parks and areas around the world to preserve and protect dark sites through responsible lighting policies and public education. This means you can see the countless stars easily and have an experience like none other.

“When you get to the latter part of June and the Milky Way starts coming up earlier in the evening... the sweep of that galaxy overhead as it lies directly overhead of the length of the canyon ... When people are out at a couple of the overlooks it completely steps them back,” said Zaenger.

Zaenger said doing the work of a park ranger is a lot different now compared to how it was in 1979. From electric typewriters to copy machines to the "cloud," the way park staff communicates to visitors has changed a lot over the decades. But the true essence of the land hasn’t changed at all.

“If you go to any park—that could be Colorado National Monument, Mesa Verde, Great Sand Dunes, Bent’s Old Fort... if I were in plain clothes at those places and just sit at an overlook or listen to people at Bent’s Old Fort in one of the rooms or out on the plaza, just listening to what they have to say, that hasn't really changed. The power of place is as powerful today as it was 40 years ago,” said Zaenger.

His last day as a Supervisory Park Ranger was October 2. Just three days later, Zaenger was already on the first vacation of his retirement and plans for many more with his wife. He doesn’t plan to move away from Montrose for the time being, with his daughter still living in town. But he hopes to explore more hobbies like playing piano or fly fishing.

One thing Zaenger will continue with from his days as a ranger is his writing. For several years, he wrote for the parks as well as in a column at the Montrose Daily Press. He published a final column just last month. He hopes to continue writing about the heritage of Colorado and the country, even the parts of history many people are not so proud of.

“Our heritage has to embody all of that. And we're coming to see that more and better, and maybe communicating with each other and how we come to grips with that better as we head into the future,” said Zaenger. “And that is glorious, I think. And I'm looking forward to just being a part of listening and in the part of sharing that as time goes on.”

Amanda Horvath is a multimedia producer with Rocky Mountain PBS. You can email her at amandahorvath@rmpbs.org.