Lifelong activist shares family legacy through Artivism

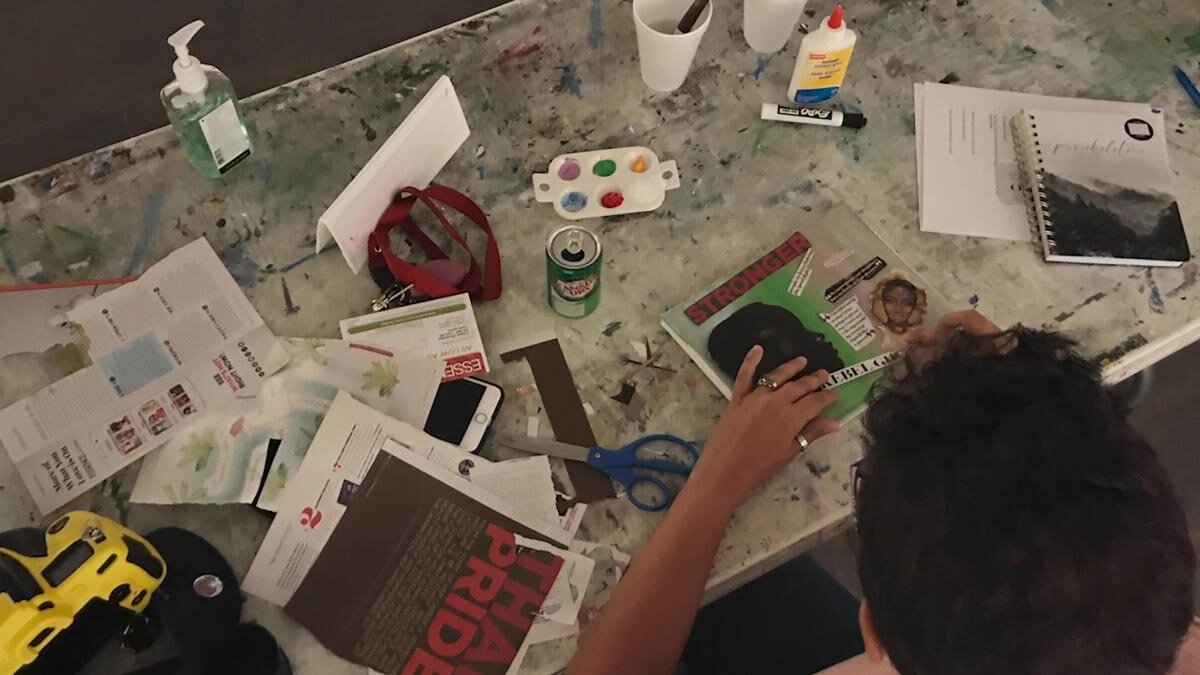

In a downtown studio in Colorado Springs, artist and educator Lisa Villanueva organizes years of artwork.

Jewelry, paintings, collages, sculptures large and small, and found and repurposed items vividly portray her life experience — all through the lens of a lifelong activist. Through almost any medium, Villanueva’s work expresses a range of celebration, culture, rage, grief, and the emotion of human rights violations of the Black experience.

Related Stories

Villanueva, originally from Chicago’s housing projects, remembers vividly one of her first experiences combining art and activism in a movement known as Artivism. She was in the sixth grade, and it was February.

“I went to the principal and asked if we could celebrate Black History Month. And she said, ‘We don’t do that here,’” Villanueva recalls.

“So I went home. I was heartbroken. In those days, there used to be a little cardboard that came in pantyhose. We were very poor, and my mom would give me those pieces of cardboard to use as sketch pads. I drew on them. I drew Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass. I drew many different posters, and on each, I wrote a little blurb.”

Villanueva arrived to school early the next day and hung the posters up and down the hall.

“My principal came down the hallway and saw them. She took them all off the wall, and tore them up,” Villanueva said. “I was so hurt.”

Her mom was called to the school for disciplinary action.

“The principal told my mom what happened, and they went into her office. There was a little ruckus,” Villanueva remembers. "And ever since then, the school celebrated Black History Month. And they did a special program just for us.”

“I think that was my first spark, where I saw that I could combine art and activism,” Villanueva said.

She now teaches Artivism coursework to people of any age, background, and skill level. It’s a method she has incorporated into curriculum — and her own practice — for over 20 years.

In her career in education, teaching math, science, and writing, “I noticed that when I incorporated art into other subjects, the kids caught on better,” she said. “A lot of my students came from oppressed areas, and they were shy, but could express themselves just wonderfully though art. I found out so much about them through their art.”

Through mediums like graffiti and journaling, Villanueva connects students to their emotions, experiences, and feelings. She has taught at all levels of school, and in facilities for incarcerated youth.

“I come in and put a piece of paper in front of them, and some colored pencils. I say, ‘Talk to me. Tell me what you want to tell me. But tell me on this paper. Any way you can,’” she said. “And it’s not just a K-12 thing. It’s intergenerational. I will teach anyone who comes to sit at the table.”

Divided into four areas, Villanueva’s Artivism course covers a spectrum of rights, including Environmental, Human, Civil, and Animal. Students get to know each other, watch presentations, listen to lectures, read, journal, and talk about their personal experiences. While students talk, they also work on assignments including drawings, sculptures, collages, and paintings.

“It’s a place where you don’t feel bad about what you say or about contributions,” Villanueva said. “Students learn to address real issues through conversation. There’s nothing like sitting across from a person and having them tell their intimate story to you. And telling them how important that story is,” Villanueva said. “It changes lives.”

She said she loves to see what students are inspired to make during these sessions.

“So much beautiful art comes out of it,” she said. “Talking while making art helps people feel comfortable. It allows us to open a line of communication about historic things that we have done to each other and to our environment that have been wrong for so long — and through this physical action, we realize we can change.”

She begins the course with a conversation on Civil Rights. Villanueva tells her students a very special story. It’s the story of her grandfather, a preacher and sharecropper who organized a strike against a plantation owner who refused to pay fair wages.

“My grandfather’s name was Owen Whitfield. He was a preacher, and married to Zella Whitfield, my 4’ 11" Black and Native American grandmother,” Villanueva said. “My grandfather met her on a reservation. They got married and became sharecroppers. Sharecropping is still like being an indentured slave. They still picked cotton, tended to farming, and worked a plantation for other people.”

Her grandparents lived in a shack with holes in the roof, and had fifteen children.

One winter, her grandfather went to retrieve his annual pay. Instead, the plantation owner handed him a used suit.

“When my aunts describe it, they say it was the first time they had ever seen him cry,” she said. “It was the end of the year, almost Christmas. And he got nothing. Nothing. They didn’t even have money for food.”

For the next year, Whitfield traveled on foot, recruiting for and organizing a strike of sharecroppers to walk off the plantation. It was 1937.

“They knew that they would lose a lot,” she said. “But they had to show the plantation owner that they needed to be paid.”

She said the KKK often came to the house looking for her grandfather.

“My grandmother always had some biscuits and a pair of socks ready out the back door, because he had to literally go into the water where the dogs couldn’t smell him and stay for a few days until the KKK left. He would have biscuits to eat, and a dry pair of socks for when he came out,” Villanueva said.

In 1939, Whitfield led the Missouri Sharecropper Roadside Demonstration, with Black, white, Asian, and Native homeless sharecropping families camping and demonstrating to raise issue with the social injustices of sharecropping. The strike was ultimately successful, capturing national attention.

“President Roosevelt sent word to my grandfather and grandmother. My grandfather met with the President, and my grandmother met with Eleanor. The President signed a bill to give the sharecroppers subsidies,” she said.

At the signing of the bill, “My grandfather wore that used suit,” Villanueva said.

Her grandfather went on to purchase land for sharecroppers to ensure they would not have to live on plantation lands, and continued to be a vocal advocate for human rights for his entire life. He passed away from cancer at home after being refused medical treatment because of his background in activism, Villanueva said.

“Every time I share his story in class, my heart is overwhelmed. I am a part of this legacy, but I didn’t start this,” she said.

She keeps a photograph of her grandparents close by in her art studio at Cottonwood Center for the Arts.

“That’s my boost,” she said. “When I learned his history, and I learned what he had done — a man with nothing, to change the world like that — I said, ‘I have to make him proud. I have to do what he did, and more.’”

Villanueva continues her grandfather’s legacy as a change agent — and in other ways.

“I’m told from my aunts that I’m just like him,” Villanueva said. “They always tease me. When I hold a book and wear a certain jacket, they say, ‘Look at her! She looks just like him!’ I take it as a great honor.”

In 2021, as communities struggle to reconcile dialogue surrounding racism in America, Villanueva said Artivism and practices like it are needed more than ever. “A lot of times we’re too afraid to really talk about what is going on,” she said. “We’re afraid to talk about violence, about this happening in our own communities. With the taking of Black lives — especially as a mother of three boys — I can’t afford to be afraid to speak.”

In her artwork, Villanueva says, “I want to evoke emotion, to remind people about the issues. I want to talk about it — to talk about what’s going on.”

These conversations, she said, are at the heart of Artivism.

“I see the transformation of people in the class. I see them come into an honest dialogue, and become comfortable with each other,” she said. “I see them become more aware. They know they have been put on this earth to do something — that we’re not here by mistake,” Villanueva said.

“Artivism is about creating a change agent. Because when they leave this class, they know that they can make a change.”

Links:

- Artivism class information at Cottonwood Center for the Arts.

- Lisa Villanueva's bio and classes at the Fine Arts Center.