In ‘The Dry,’ History Colorado celebrates Black women and the power of photography

DENVER — Consider how many small miracles need to happen to make a film photograph.

First, you need a willing subject and a capable shooter, not to mention a working camera. The lighting has to be right, of course, and the shutter must open for just the right amount of time — not too short, not too long — to allow the light to make an impression on the film’s silver halide crystals.

Then there is the alchemy that goes into the development process, which I don’t have the time (or, if I’m being truthful, the knowledge) to explain in full detail, but trust that it is not a particularly facile process.

Finally, there is the issue of preservation, which fans of “Finding Your Roots” know to be more complicated than simply stuffing photos in an old shoebox. In the case of Alice Craig McDonald, the greatest miracle is her family’s dedication to safeguarding their history, which is now on display at History Colorado.

The exhibit is called “The Dry: Black Women's Legacy in a Farming Community.” It consumes the entirety of the museum’s third floor mezzanine. Film photographs — mostly from McDonald’s family archives — cover the walls, documenting the history of “The Dry,” a predominantly Black homestead in Otero County, Colorado. Visitors can listen to oral histories of the region through interactive kiosks.

“I went all around the state trying to find Black history, saying, ‘What are the stories we know? What are the stories we maybe don’t know but should?’ That was really my first introduction to The Dry,” said Dexter Nelson II, associate curator of Black history and cultural heritage at History Colorado.

Dexter Nelson II is the associate curator of Black history and cultural heritage at History Colorado.

When Nelson joined History Colorado two years ago, his first major project was to develop the museum’s app. The app offers users a “Black History Trail,” a virtual, interactive map where people can travel through time to explore the Black experience in Colorado. In the Southeast Colorado section of the trail, you’ll encounter “The Dry.”

The history of The Dry dates back to the early 20th century. Around 1915, Josephine and Lenora Rucker — two Black women — took advantage of the Enlarged Homestead Act and moved from Nicodemus, Kansas (the first all-Black town west of the Mississippi River) to Otero County with the goal of creating, as Nelson put it, a “Black utopia free of discrimination.” Once they arrived in Colorado, Lenora and Josephine partnered with a white man named George Swink, who had connections in the irrigation industry and offered to help the Ruckers with their homestead.

The Ruckers traveled back to Nicodemus and even went as far as Oklahoma to recruit more families to join them in Colorado. One of the women who joined the Ruckers was Lulu Craig (née Sadler), McDonald’s grandmother.

Three generations, Sanford Craig, Harvey Craig Sr., and Harvey Craig Jr., 1935 (Credit: History Colorado)

What distinguished The Dry from many places in the U.S. at the time was the lack of racial animosity. In a 2020 interview with Colorado Public Radio, McDonald said “there was no racism” in The Dry.

“It was a community. Everyone helped each other out,” Nelson explained. “You couldn’t really afford to be discriminatory … because you needed someone else to survive.”

That survival wasn’t easy. As you may have discerned from its moniker, The Dry — named for the aridity of the region — was not the easiest place to make a living as a farmer. Swink built a dam for the community in the early 1920s; it broke and was never repaired. Not long after that the Great Depression hit, making a livelihood in The Dry near impossible. Many families left, but not McDonald’s ancestors.

“Instead of just packing up and leaving … they stayed here and they survived,” Nelson said. The survival was due in large part to adaptation. He said McDonald’s family pivoted constantly, from farming to dry farming to raising livesocks.

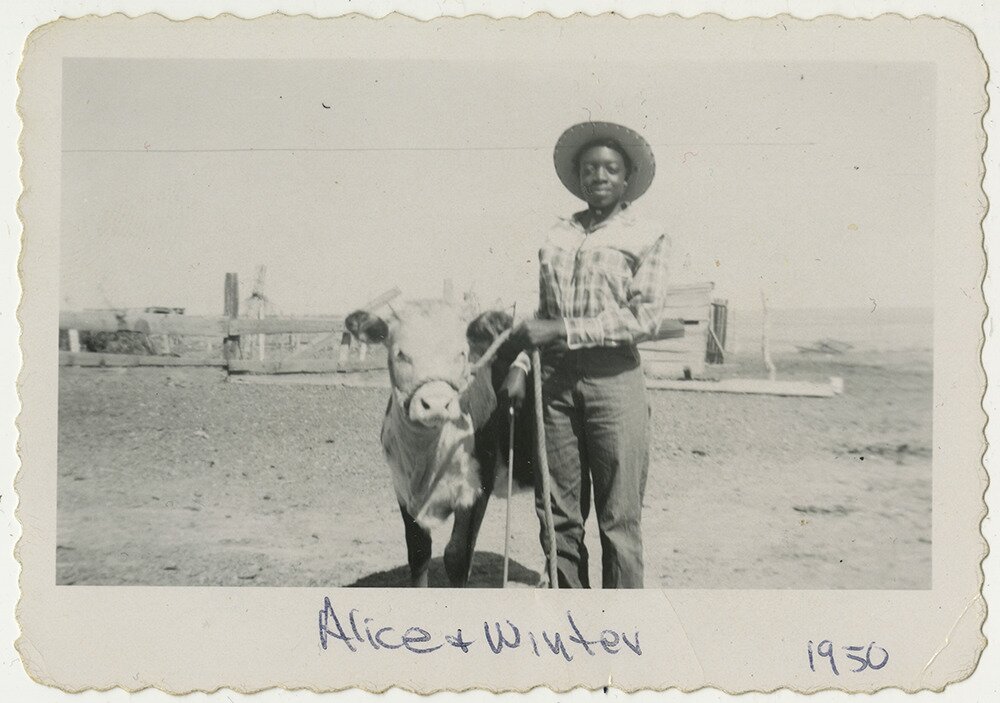

Alice McDonald and her award winning cow Winter, 1950. (Credit: History Colorado)

Nelson can’t help but be proud of the way this exhibit came together.

“This, to us, is the example of a museum in the 21st century really doing their job. We went out into community, were told about this story, now we’re telling this story with community,” he beamed. “That’s a big difference.”

McDonald will turn 90 years old next year. She currently lives just 10 miles from what used to be The Dry. And even though The Dry never achieved town status and the original buildings now only exist in photographs, we know of its history because of the people who stayed. “They’re very much keeping this story alive and well,” Nelson said of McDonald’s family.

Nelson said that McDonald’s “immaculate family records” made his job a lot easier.

“It’s really unique from the historian perspective,” Nelson said. “We’re looking for primary sources, we’re looking for books — anything we can get a hold of. But for this, if I had a question about someone who is in a photo, I could call Alice.”

Walking around the mezzanine, it was difficult not to take pity on the future historians who will one day create exhibits about our modern era. Because how many of us in this age of Snapchat, Instagram Live and other ephemeral forms of documentation are chronicling our lives with the same fastidiousness as McDonald?

“They can trace their legacy,” Nelson said, gesturing toward the tremendous photos of Lulu and other founding members of The Dry. “We are telling the story hand-in-hand with this family. Because it’s their legacy; they’re stewarding over it. And so they are allowing us to tell their story, so we’re providing a platform for that.”

For Nelson, the exhibit is not only evidence of the merits of record-keeping; it’s the continuation of History Colorado’s work in elevating the Black history of our state.

“I mentioned going all around the state, talking to people. And, you know, I would get looks of shock when I would say the African-Americans were here before 1960,” Nelson said. “We were here doing really big things and contributing substantially to the history of Colorado. This is one small part that we hope people can take away from that.”

“The Dry: Black Women's Legacy in a Farming Community” will be on display for one year. More information is available here.

Kyle Cooke is the digital media manager at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach him at kylecooke@rmpbs.org.