No security blanket: Rural Colorado jails struggle to provide mental health treatment

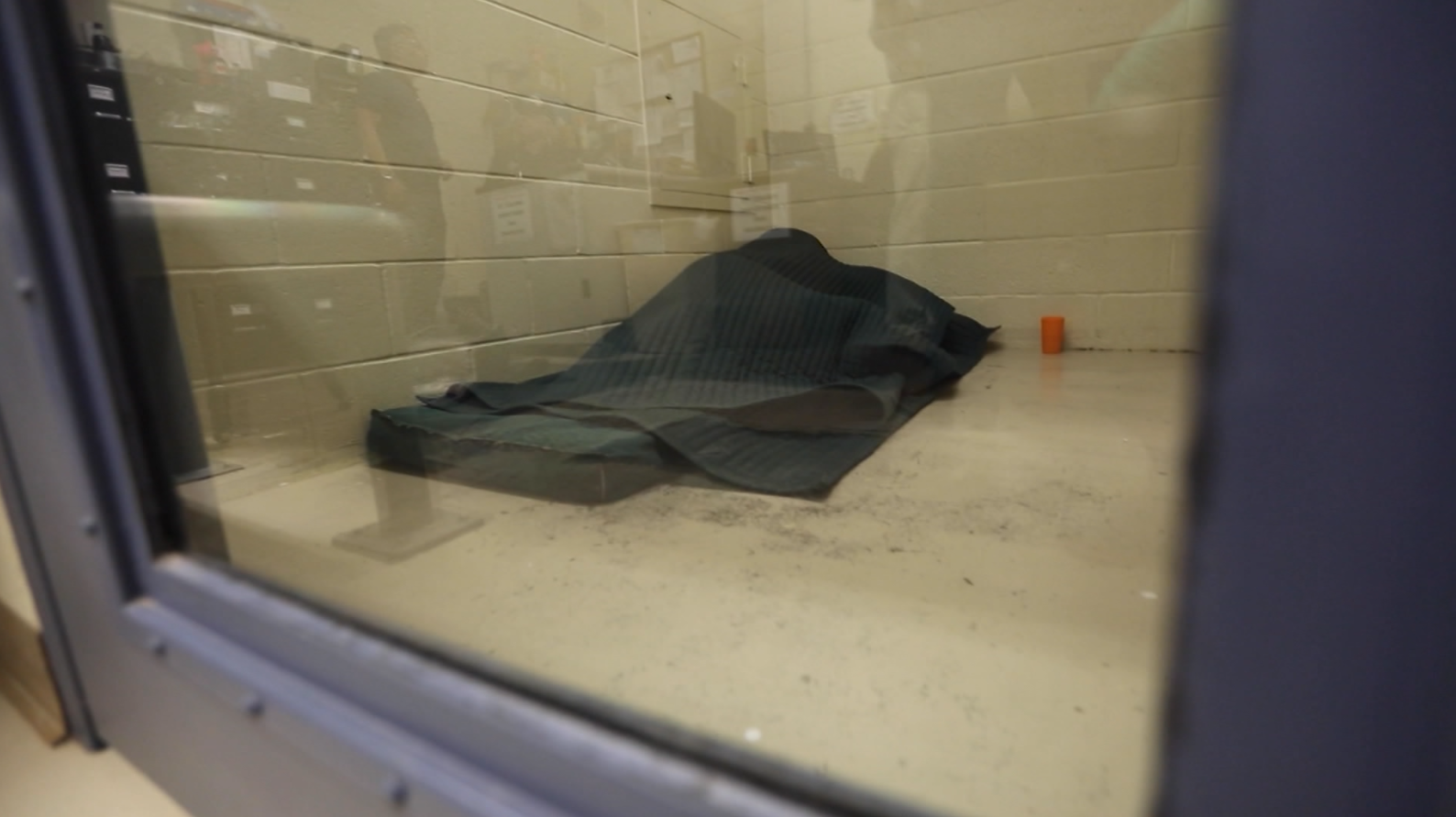

The blanket lay crumpled on the floor of a holding cell inside the Rio Grande County Jail, black and heavy like a quilt.

Every so often, an almost imperceptible quiver jostled the blanket. Only the keen eyes of the jail staff could discern the shape of a human being lying underneath.

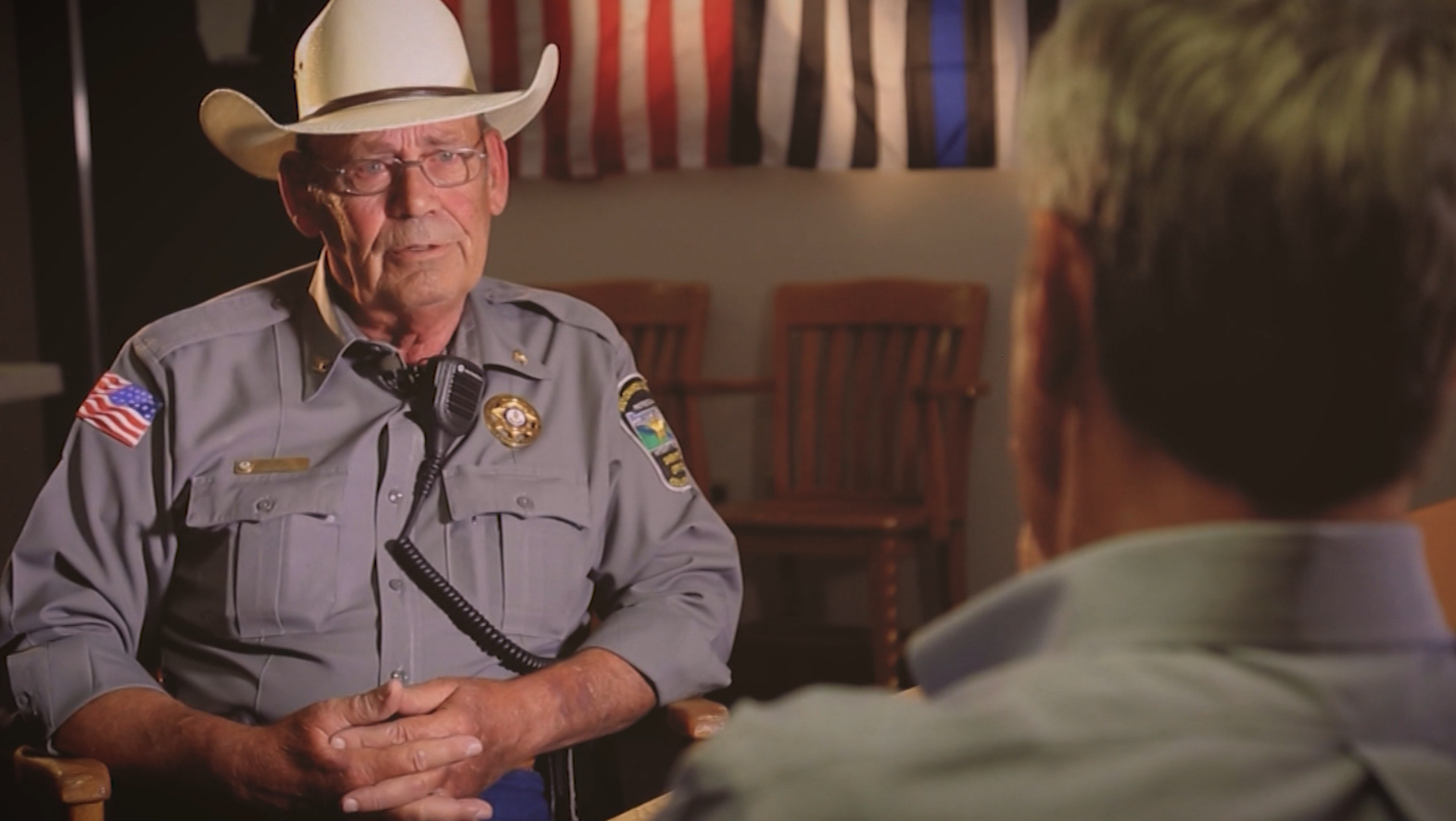

“He started hitting his head on the side of the cell wall there on the concrete cinder blocks and kept hollering that he just wanted to kill his self,” Undersheriff Ed Raps told RMPBS. “He wanted to die. And right now, he's huddled up in the corner with the blanket on top of him, away from everybody.”

A few days earlier, Rio Grande County sheriff’s deputies had transported the detainee to Denver for a mental competency evaluation. There, he tried to hang himself. Now back in the jail, the inmate was still in crisis.

“Right away he's threatened to commit suicide and we caught him trying to hang himself again,” Raps said with a sigh. “We'd give him what we call a suicide blanket ... got him calmed back down. And he'll be that way until we can figure out what else to do with him.”

Privacy laws prevent Raps from disclosing the man’s identity. But Raps said the detainee is a “frequent flyer,” one who has been in custody many times before with mental health issues. This time he allegedly assaulted a family member during a mental health crisis.

Raps and his staff were doing their best to care for him. Keeping him safe and alive was their full-time priority.

But it is not easy.

“We're trained for public safety, trained to help people, to protect people,” Raps said. “But we're not psychiatrists.”

The Rio Grande County Jail sits on a quiet block off the main strip in Del Norte, a small farming and ranching town in southern Colorado’s San Luis Valley.

The modest jail has two holding cells, each about nine feet deep and six feet wide. The walls and floors are concrete. Suicidal detainees get a tear-proof blanket and not much else. There is no padding or helmets to prevent them from harming themselves, and professional medical care is scarce.

It falls to jail personnel to monitor detainees who are in mental health crises. Undersheriff Raps told Ferrugia the suicidal man currently in his custody is just one of many detainees who end up in jail because they can’t get mental health treatment in the community.

Raps says there is no local hospital or emergency room to treat mentally ill detainees.

“We have to take them and transport them all the way to Denver,” Raps said with another sigh. “That's on our dime.”

Denver lies more than 200 miles away from Del Norte. Depending on the route, which is often determined by the weather, the trip can stretch to 265 miles. With no traffic, transporting a detainee to Denver for a mental health evaluation can take four-and-a-half hours – one way.

After factoring in bad weather, traffic delays and the time needed to complete the evaluation, Rio Grande County deputies can spend three or more days transporting detainees round trip. Often, the trips require overtime, plus the cost of hotel rooms and meals.

Raps points out the strain hits more than just the bottom line. It impacts staffing -- and public safety.

“Generally, whenever a person has a mental health hold on him,” Raps said, “we're going to have to have two officers do the transport. When that happens we’re either short back here in the jail or we're short on the road.

“It doesn't matter whether you're San Luis Valley or if you're out on the Eastern Plains, the small rural counties, we don't have the facilities. We don't have the money. We don't have the expertise to turn around and to deal with mental issues like this.”

When a detainee is suffering a mental health crisis, like the man covered under the blanket, Rio Grande deputies and staff keep watch from a desk just steps outside the holding cells. Periodically, they enter the cell to check on the person and offer calming words. But they are not trained mental health professionals.

“He should be seeing a psychiatrist daily,” Raps said in exasperation, nodding his head toward the holding cell. “He should be on probably some medication to keep him leveled out to where he don't want to hurt himself or hurt somebody else. But it don't happen down in rural areas.”

If you need mental health services, contact Colorado Crisis Services for confidential support: 844-493-TALK (8255) or text “TALK” to 38255.