Hard drugs create harder problems requiring community-wide solutions

CARBONDALE, Colo. — It’s not a “warm and fuzzy” topic, as Garfield County Commissioner Tom Jankovsky pointed out during an April meeting following a presentation by High Rockies Harm Reduction Executive Director Maggie Seldeen. At that time, Seldeen had only founded her nonprofit a few months prior, in November 2020.

But she’d spent her entire life learning the hard-earned lessons that went into the HRHR mission. And she’s living proof that, whether officials want to acknowledge it or not, the Roaring Fork Valley is not immune to the substance abuse issues sweeping the nation and in particular the state of Colorado. It never has been.

“I grew up here in Carbondale — I have lived all across the valley — and was both blessed and cursed to have a mother who was open and honest but also an addict and an alcoholic,” Seldeen said in an interview over coffee at Bluebird Cafe in Glenwood Springs, a city that is both a tourism destination and an access point along Interstate 70, known for being a drug-trafficking super highway. “I lost my mother to an overdose when I was 15 here in Carbondale. I was basically on my own at that point; the people that I do have in my life still struggle with addiction. I went out into the world and just really struggled with mental health and alcoholism for a long, long time.”

She was expelled from Yampah Mountain High School in Glenwood Springs her freshman year and was homeless for several years as a young teenager. When a man in his 20s, who was frequently in and out of the criminal justice system, would give her Valium, she took it and didn’t ask questions. Thinking about it today, it terrifies her. After all, with the infiltration of fentanyl, often as a white powder easily put into just about anything without a user’s knowledge, that same scenario could have killed her.

“I didn’t know if it was his prescription — I didn’t ask to see his bottle. And that’s what we’re seeing: pills of all kinds that are actually fentanyl,” she said.

According to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Education, the number of drug overdose deaths due to any opioid per year has, with a few exceptions, steadily increased each year, going from 110 in 2000 to 612 in 2020. The numbers are bleaker when accounting for overdose deaths due to any drug, from 351 in 2000 to 1,062 in 2020. Tracking county-specific data is much more difficult, Seldeen pointed out.

“We’re only seeing part of the picture,” she said flatly. “One issue is testing drugs in the ER — a doctor from San Francisco was telling me, ‘It’s all about clinical relevance.’ But if a family member is there asking you to test the drugs, then test the drugs. And they’re not doing that. We have no idea what’s going on with a lot of these overdoses.”

Additionally, county-specific data is often collected only for the county in which an incident occurs. So if someone from the Roaring Fork Valley goes to Denver, for instance, and overdoses, that data doesn’t reflect back to Pitkin or Garfield counties, she continued.

“I’ve seen people who are lifelong valley residents, they go to the city, they use in the city, and not only is it going to take [longer] to get our toxicology back, but they’re not going to be counted in our data,” she said. “My mom died in Adams County in a hospital. This data isn’t even part of our picture.”

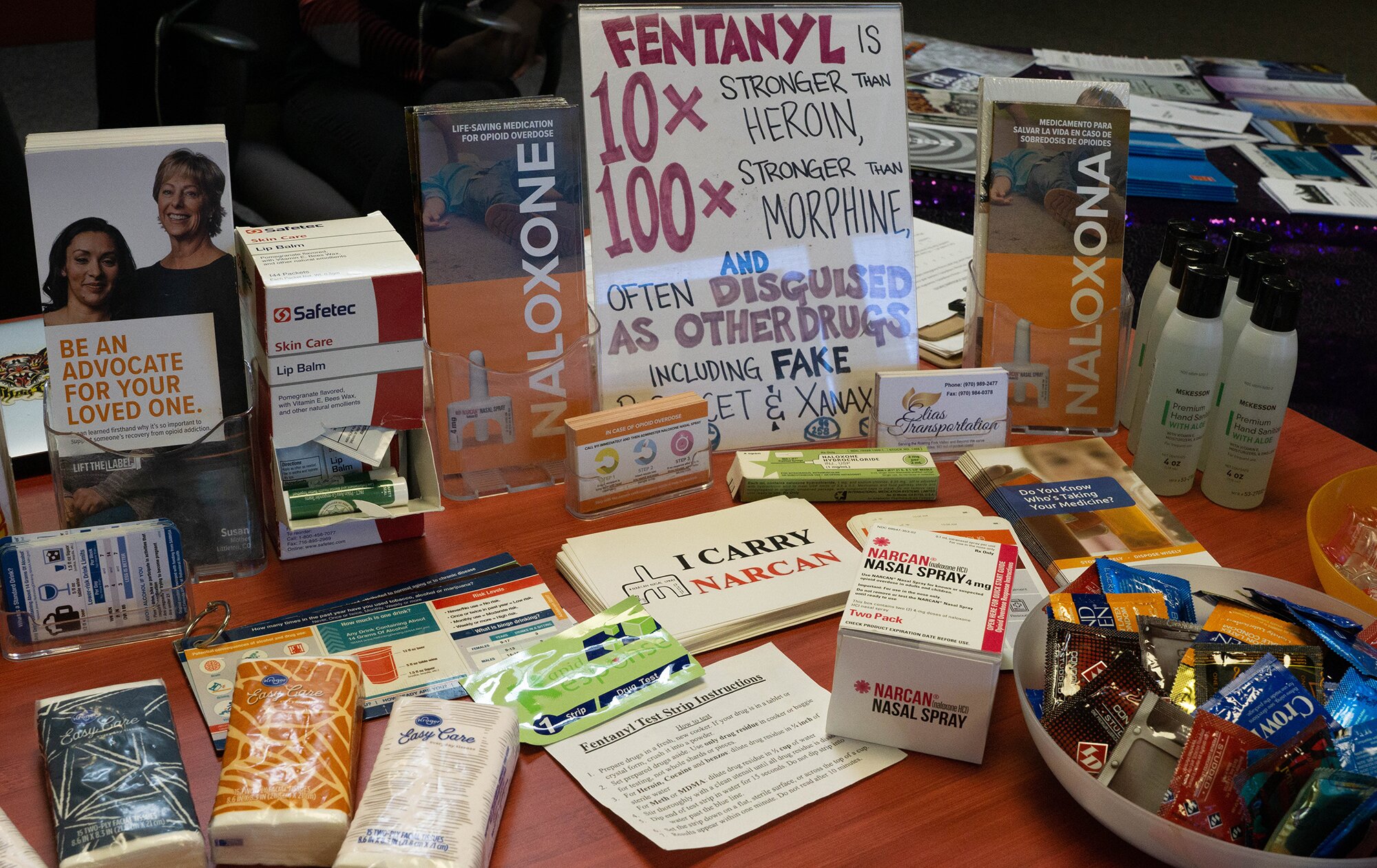

But the data she’s collecting via her nonprofit, now funded with a two-year grant from the Colorado Health Foundation, is showing at least a snapshot of the communities that comprise the valley. Among HRHR’s “three-pronged” services, as Seldeen describes it — safe syringe exchanges, peer recovery support and education and advocacy work — is fentanyl testing and Narcan trainings and administration. The sheer volume of fentanyl-testing strips her organization has distributed paints a picture of substance use.

“We just were able to aggregate our first six months of data. … Since June, [we] have given out 50 fentanyl-test strips a month on average from Aspen to Rifle, which is great, but people want full drug panel tests. So we want to do that,” Seldeen said.

And her personal experience — not to mention that of police officers with whom she collaborates — shows the very real overdoses that occur locally.

“I work with specifically the Rifle and Carbondale police departments all the time, and they call me when we have overdoses, and we use Narcan,” she said. “We are saving people’s lives in the street and in our communities. I know three people who would have been dead were it not for Narcan that I gave them. I know it would’ve been worse if we weren’t here doing this work.”

Fortunately, Aspen Valley Hospital isn’t seeing an uptick in overdose hospitalizations, Chief Marketing Officer Jennifer Slaughter confirmed after checking with both CEO Dave Ressler and Chief of Staff Dr. Catherine Bernhard, but that doesn’t mean substance use issues don’t present a real risk.

That’s what makes HRHR’s peer recovery work so critical, Seldeen said — it’s not just about saving someone from an overdose, but managing life more meaningfully as an addict. Right now, HRHR has two staff members including Seldeen, though she’s hoping to hire a third next year and continue bolstering her board of directors and volunteer base. She’s committed to ensuring that at least a 51% majority of board members and staff come from the recovery community personally.

“We’re also a recovery community organization; we have our own project board and our staff and our board are all people affected by use: either in recovery, personally affected or active use,” she said.

Empathetic and nonjudgmental communication is the only way to effectively help anyone in the throes of addiction, Seldeen said. And that means meeting people where they are and not demanding sobriety as a qualification for receiving help.

“It can be anything from getting them a social security card, getting them to their court appointment, or a lot of times just venting for an hour. We always say that an hour we spend with somebody is an hour that they’re not getting into trouble, regardless of whatever else is going on. And we also support friends and family — because we really see, behavioral health is the root of all of these issues.

“Addiction manifests in a million different ways. It can be drugs and alcohol; it can be shopping; it can be overeating; it can be undereating; it can be exercising. To me, they’re all kinds of forms of OCD,” she continued. “And all these labels, that’s not necessary. The point is, regardless, you are you and we want to meet you where you are and improve your quality of life. And we don’t necessarily think that means getting sober because a lot of people use medications that are psychoactive; a lot of people choose to continue using cannabis. A lot of people have an issue with one substance and not another.”

For her part, Seldeen’s demons reside in a cocktail. She’s been sober from alcohol for three years — but she still smokes cigarettes and occasionally uses cannabis, so she doesn’t describe herself as sober.

“It’s not about, ‘Alright, let’s get you sober.’ It’s about, ‘Let’s get you meaningful involvement — let’s get you the medical care you need; let’s get you the ID you need so that you can get the apartment.’ Whatever it is,” she said. “It’s also friends and family — we are trying to strengthen and expand craft programming, which is community reinforcement and family training. When one person is affected, the whole family is affected. And also, these are often hereditary issues. And [with] Narcan, if we save one person’s life, we just saved the whole family’s lives.”

HRHR has grown significantly since Seldeen made her presentation to the Garfield County commissioners in April. Instead of trying to offer a safe syringe exchange option in parks, which came with its own safety and security concerns, HRHR offers those services four days a week, from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., from Rifle to Aspen in facilities that believe in the organization’s work: Rifle United Methodist Church, First United Methodist Church in Glenwood Springs, the Third Street Center in Carbondale, MidValley Family Practice in Basalt and the Aspen Chapel.

“Disposal, sterile equipment — we also do pipes and safe smoking, safe snorting equipment,” Seldeen said. “Whatever your route of administration. … We have fentanyl strips. We have mail-back ones with CDPHE where you can just mail it back yourself. Hygiene products, referrals, all that kind of stuff.”

For people who cannot take part in the programs on site, Seldeen said HRHR will make delivery arrangements.

“If you can’t make it from 10 to 2 or if you’re homebound or extremely rural, call us — we’ll figure out a time to set up to come visit you,” she said.

Safe needle exchange programs are hugely important in combating another, albeit related, public health issue that’s swelling in the Roaring Fork Valley and the state as a whole: upticks in HIV and hepatitis C. In 2019, Pitkin County ranked sixth in the state for highest per capita new HIV diagnoses. In the case of Pitkin County, that meant two new diagnoses.

“It is hard when a county is smaller than 100,000 people because that data can be skewed,” Seldeen acknowledged. “We do believe, because it’s in young people, that that is because of the opioid epidemic in injection drug users. I know in my friend group, we had an outbreak of hepatitis C when I was a kid from drug use. These are definitely real issues in our community. Every life is precious — I think we can all kind of relate to that, right? Even one is too many.”

Jankovsky’s concerns that he expressed in April — that syringe exchange programs like the ones HRHR is facilitating serve as an unspoken condoning of illicit drug use — aren’t uncommon. Despite all school districts being eligible in the state of Colorado to receive Narcan through the CDPHE bulk purchasing fund created two years ago, only two have taken advantage of it: Boulder and Clear Creek in Idaho Springs.

“The general response is, ‘We don’t want to endorse people doing this,’” Seldeen said. “That’s fine, but in the event of an emergency … I don’t want to wait for somebody to die before they decide that we need it. These risks are very real, and this is the reality of drug use. And specifically, what really scares me in our adolescent communities are these adulterated pills. Xanax is a hugely popular drug right now in adolescent and rap culture, and it alone is lethal. A bar is four doses. Xanax overdoses are a thing.”

Seldeen’s goal is to build a permanent, fixed home for her organization in Carbondale. She said that with a fixed location, HRHR would be able to more easily accommodate the community’s requests — such as providing full drug-panel testing in addition to fentanyl-specific strips — while still operating satellite services. She uses a fiscal sponsor that offers administrative support and liability insurance in exchange for a small percentage of donations, which helps ensure that her and her staff’s and volunteers’ efforts remain squarely on mission-driven services, but fundraising is a central need in order to realize her dreams for the organization.

In addition to a fixed site, Seldeen would also like to see a 24/7 HRHR hotline, she said, especially so that people getting released from jail at odd hours have an immediately available resource. “My dream is to get some sort of 24/7 on-call peer support service. How can we facilitate a more coordinated re-entry for these individuals? So having somebody who’s available [is a goal]. We’ve got lots of dreams, and we’re doing lots of amazing work already.”

If it sounds like her nonprofit is a particularly sophisticated operation to be founded by a former addict who experienced homelessness and dropped out of school, that’s because while those chapters were important for forming Seldeen’s perspective, they were far from the end of her story. She later got her GED and, several years later, at 23, she went back to college. It took her eight years to complete her bachelor’s degree in psychology and sociology, which she earned in May 2020 from Colorado Mesa University.

“It took a long time and it was really on and off — and there was a lot of loss, too, and transitions and battling and getting to the root of my mental health issues,” Seldeen said. “I moved back to Colorado [from Santa Fe] in 2015 after the death of a very close friend. That kind of put college on hold for a little bit, but then I ended going back to CMU.”

It was worth the wait and the journey. It was actually a course Seldeen took during her last semester at CMU before graduating that became the foundation for what became HRHR: a political activism class.

“The final project was to develop a campaign for a social justice issue. And I had never really thought about addiction and the rights of drug users as a social justice or civil rights issue before, but it absolutely is — everyone has the right to basic health care; everyone has the right to food and shelter and clean water,” she said, adding, “to bathrooms.”

She got a job as a peer recovery coach with Mind Springs Health out of college as she also got to work founding HRHR, and it wasn’t long before the latter demanded her full-time energy.

“I think studying activism is really fascinating because you get to study the pitfalls, and there needs to be intersectionality. We can’t just say the police aren’t working and cut them out of the conversation — you have to work with the systems that exist,” she said. “And we’re lucky because we have small communities where it’s relatively easy to build positive relationships. We have positive leadership, we have great collaborations. There are amazing players and amazing work going on, and it does take time, but we are definitely moving in a good direction.”