Inside the effort to keep independent, local news alive in Colorado Springs

COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. — One week after firing almost his entire staff Sixty35 Media, executive editor Bryan Grossman published a newspaper with blank pages. It had never been done before — not during the paper’s short-lived stint as Sixty35, and not during its previous 30 years as the Colorado Springs Independent or any associated publication. But in this particular issue, when readers flipped open the News and Arts & Entertainment sections, empty columns stared back.

“We didn’t have a staff,” Grossman said, noting that the blank pages were as much a statement as they were inevitable. “We wanted to be skinny. We wanted to be sad.”

Two weeks prior, the board of directors at Citizen-Powered Media — the nonprofit entity behind Sixty35 Media — had discovered $300,000 in unaccounted-for debt. At the same time, they found more than $280,000 in uncollected payments owed to them by advertisers. The organization made immediate cuts to survive. On March 15, 2023, Grossman fired the paper’s photographer, cartoonist, critics, columnists and all but one reporter.

“I, personally, in this office, laid off seven people. One right after another,” Grossman said. “We had one paycheck per person left when we did those layoffs — one paycheck left in the bank.”

Rhonda Van Pelt, who covered the Manitou Springs beat for Sixty35, was one of the reporters fired that day.

“That had to have been one of the worst days of [Grossman’s] life,” Van Pelt said. “Just all day long, people coming and going. And people were crying.”

That’s when Sixty35 published its shortest issue ever — just 32 pages long, two of them blank — with an all-caps cover reading: “DO OR DIE.” It was a cry for help, and the start of a public reckoning with a financial crisis facing a staple Colorado Springs media institution.

Now, almost two months after publishing their life-or-death issue, nearly everything at Citizen-Powered Media has changed. The staff is completely remote after leaving their offices at a 100-year-old church on South Nevada Ave., prepping to be sold soon.

Meanwhile, the Sixty35 name (a reference to the elevation of Colorado Springs) has been retired after just a few months, replaced by two brands more familiar to local readers: the Colorado Springs Independent, known affectionately as the Indy, and the Colorado Springs Business Journal, or CSBJ.

The board behind both publications now finds itself in the midst of a tireless, desperate fundraising campaign. If successful, the campaign could save several local, independent publications from the brink of death. If not, south-central Colorado will lose an important source of accountability reporting and cultural criticism, and become the latest casualty in a national crisis for local news.

The fundraising campaign began in earnest the week after “DO OR DIE,” when a companion-issue of sorts came out: “DOING, NOT DYING.” This time, the call for help was accompanied by an apology for a rebrand that readers had never asked for.

An editorial on page two read, “get used to not seeing that name [Sixty35 Media] anymore. We heard you — and as of mid-April, we’re resurrecting the Colorado Springs Independent.”

Though it was still shorter than most, the issue contained actual news coverage — and zero blank pages. On the same day “DOING, NOT DYING” was published, management held an open forum at the IvyWild School to discuss the state of the paper with the community.

“There was a big cheer when the announcement happened… that the Indy was back,” Grossman said.

The forum also kickstarted a fundraising campaign focused on a new membership model. The goal of the campaign is to reach 2,500 members at a rate of $20 per month, per member — totalling $600,000 in yearly donations. Since that night, the team has been steadily pushing towards their fundraising and membership goals.

At the time of this article’s publication, Citizen-Powered Media has collected over $160,000 in owed advertising, reduced their past-due debt to $128,000, and raised over $55,000 from a combination of donations, subscriptions, and memberships. More than 230 people have committed to monthly recurring payments — enough for a full-time staffer or several part-timers to return.

A cautious optimism has settled over the newsroom — even as it has dispersed into living rooms and coffee shops around the city.

“I don’t expect it to be easy,” said managing editor Helen Lewis, who joined the CSBJ staff in 2016. “But I think we have worked around something that looked absolutely impossible. And there are more things ahead of us that look impossible, but I think that we’ll keep working around them.”

Grossman works on a laptop in his empty office, recently cleaned out to prepare for the newsroom going fully remote.

Several former designers and writers are back, just weeks after being fired — some returning to the same roles, and some as freelance contractors.

Grossman said that he tried to leave the door open for everyone to return — even while firing them. He assured employees as they left his office that they were not being replaced.

“I [told] them that we would have to put their services on pause until we figured some stuff out,” Grossman said.

Food writer Matthew Schniper, on staff at the Indy since 2006, served as head editor for three years. He said he held no grudges when he was let go.

“I went home with my pink slip in-hand, and finished my copy and turned it in. That’s the relationship we have,” Schniper said. “I’m gonna do my work, even if I’ve been fired already.”

Schniper wasted no time finding a new outlet for his food-centric following. On March 22, one week after being fired, he launched Side Dish with Schniper, a Substack newsletter, to continue his local food reviews and industry coverage.

So far, Side Dish with Schniper has taken off as an independent enterprise, fast approaching 900 subscribers — 120 of which are paid. His average open rate on newsletter emails is above 60 percent, an impressive level of reader engagement for newsletters. Schniper is now syndicating his news articles back to the paper each week. (Food reviews are now solely available to Substack subscribers.)

“I need to be sustainable myself. Just like the Indy, I’m kind of restarting,” said Schniper, who partially funds his journalism habit with AirBnB rentals in his home. “I’m confident, though. Just based on the early launch, this thing has a tremendous amount of support.”

Pam Zubeck, a veteran journalist with the Indy since 2009, was the only reporter to survive the layoffs. The pending cuts were an open secret in the newsroom, and Zubeck said she had some advance warning she’d be kept on.

“March 15, for me, was not perhaps as gut-wrenching as it could’ve been if I had been physically on site,” Zubeck remembered. “But I sort of had a sick feeling.”

Not everyone is coming back. The Indy can’t afford to rehire its entire staff yet, and Grossman said some haven’t been able to agree on freelance rates. But familiar bylines and columns have emerged in every issue of the resurrected Independent.

The old newsroom for Colorado Publishing House, pictured here before being cleaned out, has now gone completely remote and left empty a historic former church building.

Lewis and Grossman have remained focused on one goal throughout the company’s re-staffing efforts: keep the Indy alive.

“It’s so chaotic,” Lewis said. “From time to time I stop and say to myself, ‘Okay, this is how it feels to save a newspaper. It’s okay.’”

Building "a newspaper empire"

For 30 years, the Indy was inextricably tied to its founder and longtime publisher, John Weiss. He published the first issue in 1993, when Colorado Springs was a one-newspaper town.

For decades, the city had been home to two newspapers: The Colorado Springs Sun and The Gazette-Telegraph (now The Gazette). 40 years prior, a group of former Gazette journalists unable to resolve a union dispute with their paper founded the Sun. In 1986, the parent organization of the Gazette-Telegraph, Freedom Newspapers, purchased the Sun and immediately shuttered its operations without retaining any staff or properties.

“The Gazette bought the Sun and basically closed it down, and [Colorado Springs] became a monopoly newspaper town. Astronomical profits, beyond belief,” Weiss said. “This is way before the internet, so they had a dominant control of the media.”

As the only paper in town in the early 1990s, The Gazette was criticized for publishing editorials and opinions in support of Colorado’s Amendment 2, a ballot initiative that prohibited the state from enacting anti-discrimination protections for gay, lesbian and bisexual individuals. The amendment was written by religious fundamentalists in Colorado Springs and passed statewide in 1992. The law, struck down by the United States Supreme Court in 1996, gave Colorado a reputation as “the Hate State.”

Weiss said the main reason for founding the Colorado Springs Independent was the need for a progressive, local voice.

“We created an alternative news industry that would provide a voice for the people left out, both in the news, arts and culture, and opinion community,” Weiss said.

Through the early 2000s, the Indy built itself up into a true competitor of its print nemesis, The Gazette. Even when print publications started feeling the threat of cheaper, faster digital news, the Indy found financial footing through a new state-wide market: marijuana retail advertising.

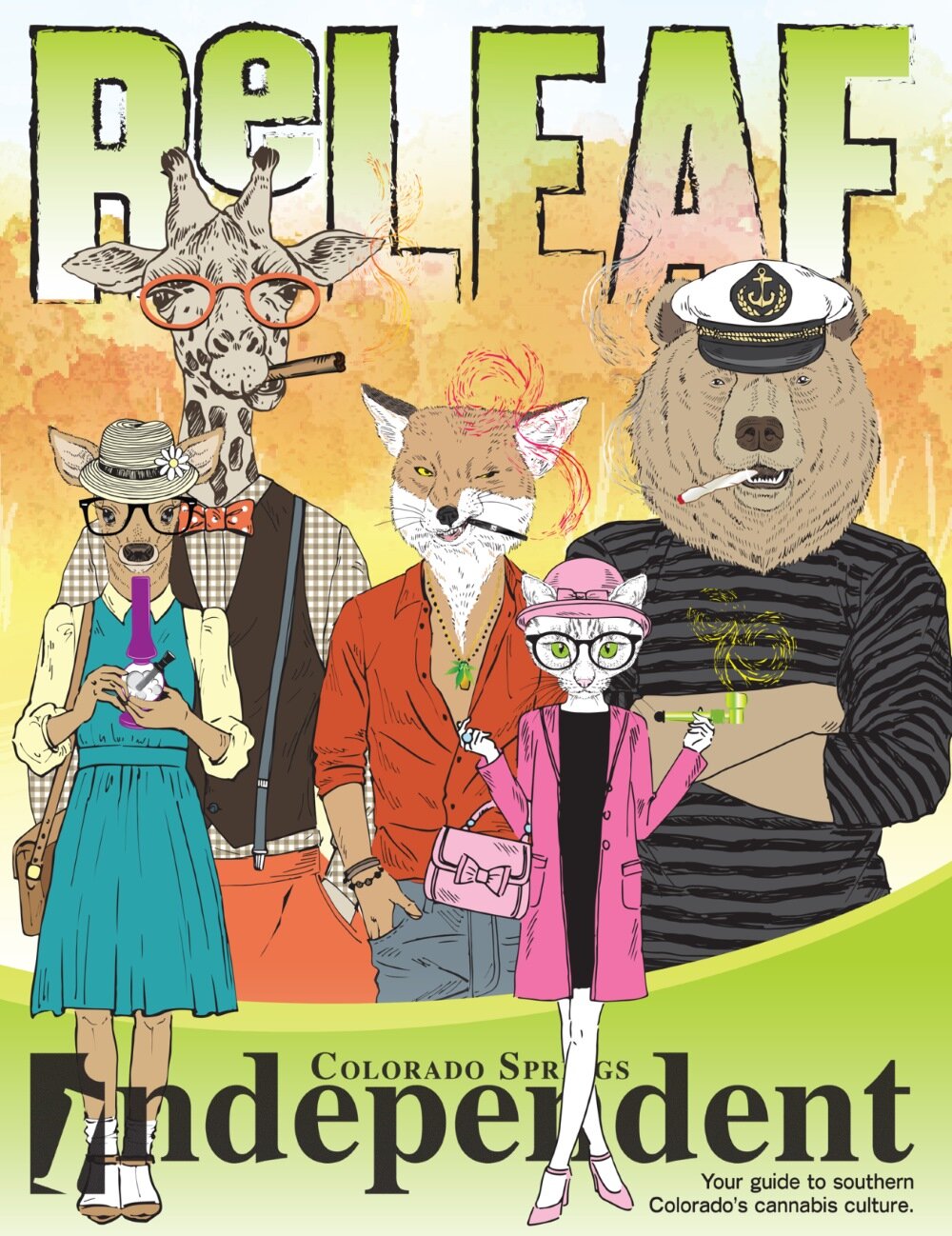

A New York Times article from 2010 cited the Independent as an example of medical marijuana ads being “New Fuel for Local Papers.” Weiss added a marijuana beat writer, a weekly CannaBiz column and a 48-page pullout supplement, dubbed ReLeaf, to the alt-weekly. Full-page cannabis ads were going for $1,100 or more.

“We know that the Indy got second life from marijuana,” said Warren Epstein, a former writer, editor, and critic at The Gazette. “At a time when everything else was hurting the newspapers, they were neck-deep in marijuana and loving it.”

During this period, Weiss accumulated a series of other publications under the banner of his parent company, Colorado Publishing House, and also founded two nonprofits — a newspaper called the Southeast Express (covering historically underserved neighborhoods in Colorado Springs) and IndyGive!, a philanthropic organization.

One unique phase of Weiss’ expansion efforts took place in Hawaii, where Weiss co-led an effort in 2021 to revive the independent, local MauiTime newspaper — now called Maui Times. The Hawaii paper currently publishes monthly issues in print and online, and its website, MauiTimes.news, promotes local events in between each issue.

“I helped revive Maui Times to the best of my ability,” said Weiss.

Under the name J. Sam Weiss, he is referenced in the Maui Times revival announcement as a senior consultant for the relaunch. Weiss is no longer associated with Maui Times, which he said has been run as a nonprofit during and after his involvement.

“I think that John [Weiss] liked the idea of having a newspaper empire,” Epstein said.

Through the years, the Indy became the feisty, left-wing, alt-weekly heart of Weiss’ empire. At its height, Weiss published eight local papers through the Colorado Publishing House: the Independent, Colorado Springs Business Journal (a business-to-business journal), Southeast Express (a nonprofit paper), The Pikes Peak Bulletin (Manitou Springs’ long-running local paper), The Transcript (a legal publication), and three military newspapers distributed at regional bases.

“When we were at our maximum, we had around 50 full-time and around 100 part-time people,” Weiss said, citing everything from delivery drivers and freelance writers to editorial and IndyGive! staff.

But even while growing his brand, many of the papers Weiss acquired were in the midst of a slow demise. CSBJ remained profitable, while others gradually shrunk. By the time of the March 15 layoffs, the editorial staff for the entire operation had been whittled down to just four people: two editors, a copy editor and Pam Zubeck.

It was a far fall from the staff of over 150 that Weiss claimed in the heyday of Colorado Publishing House.

Zubeck, one of the city’s most prolific and well-connected investigative reporters, wrote nearly every story published in-print and online for weeks following the layoffs.

“I knew that my workload would change, and I spent 32 years in the daily world, so I understood how to feed the beast, as we say in the business,” Zubeck said.

The former newsroom was covered wall-to-wall in graffiti writing and art.

Even while publishing four or more stories per day, Zubeck still managed to deliver several in-depth stories with word counts over 3,000. But the paper was destined to miss important coverage if it continued relying on a single news reporter to cover a city with half a million residents.

In Colorado, daily newspapers have suffered losses right alongside alt-weeklies like the Indy. The Denver Post, once the state’s biggest newsroom at over 300, was slashed to just 70 journalists in 2018. Denver’s other big paper, The Rocky Mountain News, closed over a decade ago and stalled in a comeback attempt.

Today, many are turning to nonprofit news as a model to curtail the loss of print newspapers.

Following the example of successful publications in other states — such as The Texas Tribune and Block Club Chicago, both of which have grown in recent years — the Denver-based Colorado Sun launched as a nonprofit in 2018, giving new life to the name of the newspaper once eaten whole by The Gazette.

The Indy and CSBJ’s business transition came after years of financial losses, with the hope that a nonprofit model would provide financial relief.

Schniper said the Indy has needed a cash infusion for a long time.

Matthew Schniper has launched his own Substack newsletter for Colorado Springs food coverage, after working continuously at the Independent from 2006 until his firing on March 15, 2023.

“It was just a constantly shrinking newsroom, and doing more with less, or trying to do the same with less. And it’s just a sad state of affairs,” Schniper said of his seven years as an editor.

During the final years under Weiss, internal conversations had begun to address the idea of an organizational rebrand to accompany the shift to a nonprofit model. There was talk of an “uber-publication” that combined all Colorado Publishing House brands into one paper — an idea that would eventually develop into Sixty35.

"It was a mistake"

As with most financial crashes, it happened over a long time and all at once.

Weiss reached a breaking point with Colorado Publishing House in 2022. The pandemic had only intensified the financial stress from years of declining ad revenues and increasing print costs.

Nobody was laid off during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, but everyone took a pay cut. Advertising revenue was scarcer than ever, and the marijuana ads that were once a lifeline for the paper had all but disappeared.

“The papers, which used to be profitable, were — for a variety of reasons dealing with industry trends and other things — were break-even [or] minus,” Weiss said. “We needed to make some changes, and I didn’t feel like I was the leader to bring us into the print-digital age.”

Weiss stepped down as publisher and, according to Grossman, gave the management an ultimatum on his way out: find a new financial model or close. Weiss and management settled on a nonprofit model, and sought out an established 501c3 in town as a parent company.

Before leaving, Weiss appointed a team of reporters, mostly from the Business Journal, to oversee the transition. Amy Gillentine, former publisher and editor of CSBJ, was named publisher. Grossman and Lewis were appointed as editors, with Grossman taking on the unprecedented role of overseeing all of Colorado Publishing House’s papers simultaneously.

One parent company the Indy considered nesting under was Give! — the philanthropic network that Weiss himself had founded in 2009 under the name IndyGive!, which provided fundraising support for nonprofits in the Pikes Peak region. Give! became an independent nonprofit in 2016, financially and organizationally separate from Colorado Publishing House.

According to its website, Give! has helped 255 local nonprofits raise more than $17.5 million through more than 120,000 donations since its founding.

But despite the philanthropic network’s connection to Weiss and the Indy, their talks never materialized into a new partnership.

“There never really was a solid, you know, detailed proposal or plan for that,” said Barb Van Hoy, former executive director and current board member of Give!

In April 2022, the board of Give! elected to remain a separate organization, but Van Hoy said she could never have predicted what happened next. As the first in a series of dramatic developments, Weiss, Gillentine, and board chair Ahriana Platten published a jarringly critical, yet opaque editorial in the Indy to sever ties with Give! One excerpt read:

“On advice of legal counsel, we are unable to air all our concerns at the present time, but suffice it to say we no longer can vouch for the integrity or honesty of IndyGive!’s current board members. This was a heart-wrenching decision, but the IndyGive! board’s unacceptable and unprofessional behavior leaves us no other choice but to make a public announcement.”

Although the two organizations have been formally separate businesses since 2016, the editorial referred to Give! exclusively by its former name, IndyGive!. The original print article carried the subheader: “Legal options being explored.” (The online posting has since removed that subheader.)

Page 3 of the April 20, 2022, issue of the Independent featured an editorial explaining that Colorado Publishing House would “sever ties” with the Give! Campaign and that “legal options” were being explored.

One year later, Van Hoy remains surprised by the sudden tone shift, saying that the two organizations had an opportunity to retain a “close, cross-promotional partnership.” She insisted that the talks between the two organizations had been “amicable” until that editorial was published.

“The Indy and the Business Journal were the biggest media partners [for Give!],” Van Hoy said. “We were really sad.”

Weiss said that he was sad as well when the split occurred. Reflecting back on that editorial now, however, he takes a far more positive tone.

“In my mind, promises were broken.” Weiss said. “But my hope is that, one day, the Independent will be able to partner with the Give! campaign again… we want the Give! campaign to thrive.”

The breakdown of that relationship has shapeshifted into something more ironic, now that the newspaper itself is a nonprofit in the midst of a fundraising campaign. During their first full year without the Indy or CSBJ as media partners, Give! raised $1.2 million for 74 nonprofits.

Platten hopes that the two organizations can find a way to collaborate again in the future.

“We’ve done some mending of fences,” Platten said. “I can’t speak for Give! I can speak for us and say: hindsight is 20/20… We realize that we could have done some things differently and probably had a very different outcome.”

The Colorado Publishing House did eventually find a home at the nonprofit Citizen-Powered Media, or CPM, originally founded by Dave Gardner in 2006 to support his regional podcasting network.

Gardner was previously the general manager for another local media organization, KCMJ, a now-defunct community radio station that launched on local 93.9 FM in 2016. Gardner left KCMJ just after the FM launch. The station closed in 2021. A user named Davegardner80906 edited the Wikipedia entry for KCMJ-LJ in April 2022 to add commentary about the closure, claiming, “After a group with no radio experience and no management expertise took over the station, it fell into disarray.”

As someone who has worked in media for decades, Gardner helped Sixty35 Media initially launch their podcasting efforts and hopes to do so again in the future, once the Indy and CSBJ stabilize. For now, podcasts are on-pause.

CPM took on a greater scope when it became the home for the Indy and CSBJ, but the acquisition was not a purchase. Weiss donated all assets from the Colorado Publishing House to CPM, who then became rent-paying tenants in Weiss’ building.

“I think that’s a misperception out there is that John Weiss sold, sold this publishing empire to Citizen-Powered Media,” said Gardner, now vice president for the board. “He donated it. He just gave it away.”

The financial implications of Weiss donating the papers are unclear, since the company valuations are not known. Along with being a gift to the community, the donation of the papers could have also been a tax-savvy financial decision.

“We did not do this as a tax write-off,” Weiss said. “The goal was to turn this over to the community to be run by journalists.”

Weiss did acknowledge that he is looking into tax-related elements of his donation, but said that it was not a factor in his decision to donate, and he did not formally determine the worth of Colorado Publishing House before giving it away.

If newspaper ownership trends around the country are any indication, it would’ve been difficult for Weiss to find a buyer outside of one of the hedge fund-backed conglomerates that are decimating local newspapers nationwide. Aside from notable exceptions like The Boston Globe and The Washington Post, very few papers around the country have undergone a sale to individuals with the money, time and interest to become local news moguls.

So, after decades of pouring his own money into the publishing house, Weiss handed it off to his hand-picked successors. Sixty35 published its first issue on January 11, 2023.

“The name-change came out of conversations about that uber-paper. What if we combined all of these properties into one publication?” Grossman said.

Sixty35 had been used internally for years as an example for potential rebranding. Over time, the name became so worked into discussions about potential rebranding that it became difficult to imagine another one, Platten said.

Stacks of old issues of Southeast Express were among the items being cleared out of the old newsroom.

But two weeks after the first issue of Sixty35 hit newsstands, Amy Gillentine abruptly announced her resignation. She served as publisher for just three months. Platten, who remains chair for the board of directors, became the interim publisher.

Gillentine has not publicly disclosed her reasons for leaving, but every person interviewed said they were surprised by her departure.

“My reason for leaving was completely personal,” Gillentine said.

Once Platten stepped in as the interim publisher, the board discovered it had been receiving inaccurate financial reports. According to the reports that the board was receiving, Platten said, they were in the black.

“I honestly cannot tell you how they got the figures that they had,” Platten said.

The debt was attributed mostly to “the transition to a nonprofit,” although mysteries remain around the $300,000 that went missing so quickly and the financial reports that failed to include those numbers.

“I think it would be safe to say, ‘oh, sh*t,’” Gardner said, when asked about discovering the debt. “We did not have a clear picture. And we suddenly began to get clarity that we had a lot of work to do.”

Editors and board members said the financial misreporting was due in large part to an overextended staffer who lacked the necessary experience that a massive business transition required. The previous business manager had left the company earlier in the year, and responsibilities were handed over to “somebody much less skilled,” Platten said.

Once the debt was fully revealed, that person was quickly moved into a minor data-entry job, and replaced by a professional bookkeeper brought in as an independent contractor, a decision reflective of Weiss’ mantra: to be “hard on problems, and soft on people.”

Gillentine did not respond to a question about her own knowledge of financial mismanagement, and others interviewed suggested she was not to blame.

“We are not of the opinion that there was malfeasance; we are of the opinion that things were done wrong, not entered right,” Platten said. “And there were definitely some things that we were not told.”

One source of solace was that the papers had around $280,000 in unpaid advertising dollars waiting to be collected, nearly equal to their debt. Platten said that advertisers had been able to run late on payments as a result of “general goodwill” between local, small businesses.

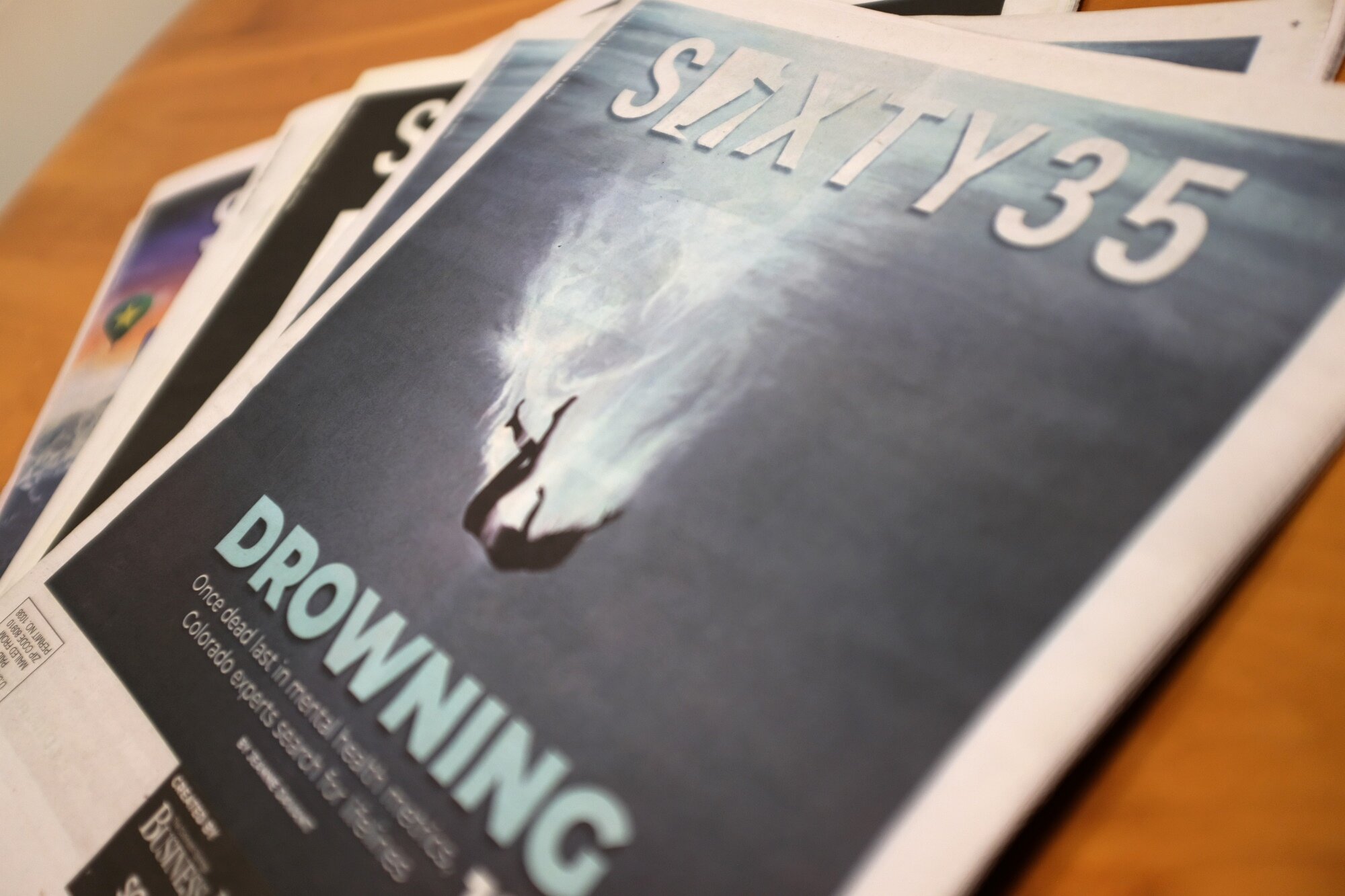

Only 13 issues of Sixty35 were ever printed. The final issue, dubbed “Drowning,” published a long-form cover story about the mental health crisis in Colorado Springs.

Of the total amount that CPM had yet to collect, the board calculated that close to $230,000 was retrievable. (The rest was owed from businesses that had closed down.) More than half of that retrievable amount has been collected so far.

“Now that [advertisers] understand that we are struggling, people are being really good about paying,” Platten said. “Collecting back-due amounts have really made the difference for us.”

Platten’s team has been tremendously successful thus far in staving off the worst financial outcomes, such as bankruptcy and closure. CPM has now paid back most of its debt by cutting costs and fundraising.

But financial mismanagement was only one of the problems at hand when Platten took over as publisher. The new title, Sixty35, simultaneously sent the paper into a branding and identity crisis.

“That rebrand was difficult for a lot of people,” Lewis said. “We lost all the brand recognition that we had… Our goodwill took a bit of a hit.”

The intention behind combining all Colorado Publishing House papers into Sixty35 was two-fold: to save on printing costs, and to bolster the amount of content included in their flagship publication.

But readers were never convinced that they were actually getting more. Some saw the name as a knock-off of Denver’s 5280 magazine, or felt that the combined publication was only a diluted version of each of its parts.

Advertisers were frustrated, too, and doubted that readers would be loyal to an unknown entity.

“We realized that we couldn’t be all things to all people,” Grossman said.

Indy readers were in fact getting more in their weekly issues: a longer newspaper with expanded military, business and neighborhood coverage. They just didn’t necessarily want the extra content they were getting — especially not in a package they didn’t recognize.

Others, like Pikes Peak Bulletin readers, were getting decidedly less coverage of their hometown. The Bulletin, a Manitou Springs-based weekly with a history dating back to the late 1800s, went from its own full newspaper to a mere few pages inside of Sixty35.

“Typically, our issues were about 24 pages,” said Rhonda Van Pelt, the Bulletin’s co-editor. “So we went from that down to one or two pages in the Sixty35 publication. And I kept really busy editing and posting everything else online.”

It wasn’t long before the team at Sixty35 Media relented. The issue was not readers struggling with change, they conceded; the issue was a poorly executed rebrand.

“It was a mistake,” Grossman acknowledged.

The Pikes Peak Bulletin in Manitou Springs has a history that dates back to the late 1800s. (Photo by Rhonda Van Pelt)

When the end of Sixty35 and the return of the Indy was announced on March 23, Grossman and his team effectively abandoned years of work and planning.

Last year, ahead of the rebranding, local marketing agency Magneti was brought in.

During a phone interview with Magneti CMO Ben Robb and Platten, Robb clarified that the rebrand was for the umbrella Colorado Publishing House, not for the Indy or “any specifically beloved brands.”

Robb declined to comment further about Magneti’s work or contract with Sixty35 Media.

“We think that the team at the Colorado Springs Independent and Colorado Publishing House does vital work. And we think that they’ve got many years of crucial contributions to make to our community,” he said.

Platten shared similar praise for Robb, saying she “would work with Ben [Robb] in a heartbeat for anything.”

But others at the Indy shared frustrations with Magneti’s work. One editor described the end of their contract as “drama,” saying that they were denied access to web editing tools after the creation of the Sixty35Media.org website. A writer called the website’s search functions “completely unusable.”

Workflow issues are a given on any new website. But Sixty35 wasn’t around for long enough to work through any of those disputes.

Upon the completion of Magneti’s contract with CPM, Sixty35 amounted to nothing and was ultimately replaced by its own predecessors. Today, the old Sixty35 url gets automatically redirected to CSIndy.com. Neither Sixty35 Media nor Colorado Publishing House are included anywhere on Magneti’s website.

“It just makes you bang your head on a wall,” Grossman said, “because I can’t tell you how much time I spent in meetings for this.”

Weiss reflects on the brief Sixty35 Media era as a blunder.

“I don’t want to go into the details, but I wish we had done the transition differently. Good intentions, but very bad execution,” Weiss said.

Much of the response to the 13 issues of Sixty35 that were printed came down to simply, “I want my Indy back,” Lewis said. But she and Grossman maintain that every issue of their “uber-pub” was excellent in terms of content and design.

“When you put your heart and soul into something, it’s supposed to work out,” Grossman said. “It does in the movies. It does in the books. And maybe it will. It’s just a different ‘work out’ now.”

Return of The Bulletin

In the neighboring city of Manitou Springs, The Pikes Peak Bulletin — another long-time local publication that had been a part of the Sixty35 Media conglomerate — has changed ownership and will return in-print as a separate nonprofit.

Entrepreneur and chef Lyn Ettinger-Harwell is the Bulletin’s new publisher, having taken over the publication in April 2023. The return of the Bulletin is noteworthy in Manitou Springs, a town of around 5,000 residents, compared to nearly 500,000 in Colorado Springs. Without the Bulletin, Manitou would have no locally dedicated news outlet.

“We’re in a news desert,” Ettinger-Harwell said of Manitou Springs. “We need a credible, reliable source of news. There’s misinformation out there right now.”

The team bringing the Bulletin back to Manitou Springs includes Lyn Ettinger-Harwell as publisher (right), Rhonda Van Pelt (middle) and Bryan Oller (left) as co-editors, and Chloe, Ettinger-Harwell’s dog.

Ettinger-Harwell is a managing partner at SunWater Spa in Manitou and has run a number of restaurants and small businesses in Colorado Springs. But journalism will be a new adventure for him.

“I’m a spiritual kinda guy, and I had some rather frank conversations with God or the powers that be about it,” Ettinger-Harwell said. “I’ve been involved with a lot of incredible projects and people in my life. But this is probably the most significant endeavor.”

Veteran journalists Rhonda Van Pelt and Bryan Oller will serve as co-editors of the Bulletin. Both were part of the March 15 firings at Sixty35.

“When my layoff happened,” Oller said, “[Grossman’s] way of doing the deed was heartfelt. I left on a very sad note, but a very good note.”

Van Pelt immediately wanted to bring the Bulletin back in some form. Just hours after both were fired, Van Pelt approached Oller about collaborating to resurrect the paper. In fact, she had already been thinking of starting a Manitou Springs-focused newsletter as a back-up plan, in case things “went south” at Sixty35.

Oller spent 25 years as a photojournalist at The Gazette and almost two as a staff photographer for Colorado Publishing House. Van Pelt overlapped with Oller at The Gazette for a decade as a copy editor and writer, spent five years as a reporter for the Indy, and has served as the sole editor of the Pikes Peak Bulletin for the past eight years.

Despite their credentials, they needed someone to take on the business side, a role that Ettinger-Harwell stepped into eagerly.

Ettinger-Harwell said that the Bulletin will feature familiar bylines, including Warren Epstein, former Indy writer John Hazlehurst, and Ralph Routon, a longtime journalist and one of the four current board members at Citizen-Powered Media.

“We relate to each other through the paper, through the stories, through the coverage,” Ettinger-Harwell said. “It’s the lifeblood of a small community, like Manitou.”

The new Bulletin — slated to be back to weekly installments by summer — will cover Manitou Springs, Old Colorado City, and Lower Ute Pass along the US-24 highway.

With Oller and Van Pelt as the only full-time staffers, the Bulletin will be significantly less expensive to run than the Independent. It’s also continuing a legacy — Manitou Springs has had its own newspaper since before Colorado Springs was founded as a city.

After some negotiation between the two sides, all assets for the Bulletin were donated by CPM, including the old subscription list and website.

“We are very happy to be able to hand that off to a great team of people who really care about Manitou and really understand how important that paper is to that community,” Platten said.

And the project has local support. One anonymous donor has already pledged to match donations up to $50,000. And reportedly, advertising interest is up.

Just like the Indy and Side Dish with Schniper, the Bulletin is starting fresh. There’s excitement for the possibilities of reinvention and an overall expanded mission. But it’ll need community buy-in to become a viable business.

"Not out of the woods"

The words “always FREE” remain painted on Indy paper stands around the city. As far as management is concerned, that’s still true. The $20-per-month memberships are recurring donations, not subscriptions. Members will receive special perks, including early access to the news, free and discounted events, and more.

CPM’s fundraising campaign is focusing on a variety of revenue streams, including grants, one-time donations, subscriptions, memberships and advertisements.

When asked about the most important funding source, Weiss didn’t hesitate.

“Advertisers,” Weiss said. “The most important aspect is advertising. And advertising works when we have readers. And I believe the new format will have sufficient readers.”

According to Gardner, the key to the campaign’s success will be its membership drive.

Indy newsstands around the city bear the phrase “always FREE” on the front.

“The community still does have to get used to the idea that [the Independent] belongs to them,” Gardner said. “It doesn’t belong to John Weiss anymore. And so our community has to step up and become members, subscribers, donors. We have got to support this if we want it to survive and thrive into the future.”

Community ownership is a big shift from the established norm in Colorado Springs, where the Indy has been free for 30 years.

“That has been the biggest change for us, is taking a free newspaper and literally assigning a dollar value to it,” said Tracie Woods, who manages CPM’s events and memberships. “But keeping it free is the goal on the street and online. We’re adamantly opposed to paywalls.”

The board is still hoping to reach their goal of 2,500 members, and membership growth has slowed a bit in recent weeks. Platten thinks that it might be a result of people seeing the Indy back on newsstands and falsely believing that donations are less needed.

“It feels like success when you get that paper in your hands,” Platten said. “And it is success. It was a huge amount of work for us to get there. But financially we are still relying on membership to get to a position where we are sustainable.”

With just 233 members upon last report, CPM is a long way away from the 2,500 that it needs to sustain operations. 2,500 members at $20 per month would add up to $50,000 in recurring monthly funding, and payroll for the Indy and CSBJ is $49,500.

As a nonprofit, CPM cannot rely on grant funding to support operations and staff salaries. They’ll need donations and advertising to cover that. But advertising revenue is mostly needed to cover printing expenses.

“The most important work to getting a new publisher is for people to jump online and become members immediately,” Platten said. “The second [most important] is to use the advantage that the Indy and the Business Journal have always had, which is amazing reach in this market for advertisers.”

Another looming threat is the possibility that the Indy’s former office building gets demolished by its next buyer — a serious prospect, given the rate of development in downtown Colorado Springs.

The building is one of Colorado Springs’ few remaining gems from the turn of the 20th century. It was designed by Thomas McLaren, the Scottish architect responsible for several of the city’s National Historic Register listings. Construction on the once-United Brethren Church began in 1912 and finished in 1917, delayed due to World War I.

For the past century, the building has served a wide variety of purposes, from police training center to the former Smokebrush Theater, and, for the last 20 years, the Indy’s newsroom.

Weiss still owns the building, but will sell it soon.

The old United Brethren Church on South Nevada Ave. is being sold soon, after 20 years as the newsroom for the Independent, and its new owners will need to determine whether to find a creative use for the historic building or to demolish it.

“My hope is that a church, a nightclub… somebody will be able to make magic out of the building like we were able to do,” Weiss said.

Regardless of the fate of the building, staff will remain off-site, saving over $100,000 in rent and maintenance costs each year. Most of their staff was already working remotely. Many stopped coming into the office altogether during the pandemic and never returned.

Lewis and Grossman spoke to RMPBS from the inside of Grossman’s empty office in the building — entirely bare, except for a desk, a futon, a recently cleared-out shelving unit, and a neat stack of framed images that had once adorned the walls.

To visualize their steps toward future success, Grossman and Lewis said they are using the metaphor of “a Yeti making his way across three mountain peaks.”

The first peak represents the ‘Stabilize’ phase — where the Indy and CSBJ currently find themselves — followed by ‘Sustain’ and, finally, ‘Grow’.

Ultimately, the success of this campaign won’t just determine what’s next for a small, independent newspaper. The implications of their membership campaign are much bigger; it will determine the future of the news landscape in Colorado Springs.

As a growing city with an already limited news presence, a total loss of the Indy would severely limit the amount of accountability journalism that Colorado Springs needs. And it would all but extinguish the cultural criticism that the Indy has defined for three decades.

“It’s a critical part of democracy,” Lewis said. “It’s essential.”

Zach Ben-Amots is an investigative multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach him at zachben-amots@rmpbs.org.