Cases of black lung are surging on the Navajo Nation, but miners lack access to care

KAYENTA, Ariz. — As cases of black lung among former coal miners on the Navajo Nation surge, a new study points to inequality in health outcomes faced by Indigenous people in the western United States.

Alex Osif, a former coal miner and Benefits Coordinator for Canyonlands Healthcare in Chilchinbito, Arizona, says over the fall of 2023, cases of black lung boomed in the area.

“Three months ago, I had only six. [Now] I'm past 50,” said Osif of the increase in black lung cases.

In a partnership with KSJD News in Cortez, Colorado, Rocky Mountain PBS is reporting on respiratory disease related to coal mining in the Four Corners region.

The most recent data from the CDC show there are 10 active mines in Navajo County, Arizona. Neighboring counties are home to dozens more.

From 1973 until 2019, the Peabody Western Coal Company operated the Kayenta mine, which produced million tons of coal per year. However, the electricity generated by the coal was sent out of the region to places like Southern California.

The Navajo Generating Station — the West's largest coal plant — was demolished in December of 2020. Ninety percent of the plant's employees were Navajo. The San Juan Generating Station, a coal-fired power plant in Waterflow, New Mexico (right on the border of the Navajo Nation) burned its last bit of coal in the autumn of 2022. Both closures were part of a wave of shuttering coal-burning plants in an effort to fight climate change.

Today, the relationship between the Navajo Nation and mining remains complex. Many in the area protest drilling and mining, though others argue that jobs in the mines and plants keep people employed on their ancestral lands.

The new study, conducted by National Jewish Health in Denver, found Indigenous miners in Arizona diagnosed with black lung are less likely to receive federal benefits from the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) using current standards for lung function, as opposed to standards specifically geared towards Indigenous people.

The Department of Labor standard measures “forced expiratory volume,” or the ability of the lungs to breathe out, and was created without a “substantial sample of healthy U.S. Indigenous individuals,” according to the National Jewish Health study.

The NJH study says that, based on the DOL standard, 33% of Indigenous miners wouldn’t qualify for benefits.

Black lung is a catch-all term for debilitating respiratory diseases like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pulmonary fibrosis and coal workers’ pneumoconiosis.

Former KSJD reporter Chris Celements, left, talks with Alexander Osif at the Canyonlands Healthcare office near Kayenta.

Photo: Joshua Vorse, Rocky Mountain PBS

Hazardous work conditions can lead to miners contracting these diseases later in life.

The lungs develop scar tissue, called fibrosis, that fights the presence of coal dust particles. That tissue grows thicker, making it difficult for the lungs to absorb oxygen. If the lungs can’t absorb enough oxygen, patients will have trouble breathing or shortness of breath.

Miners in the Kayenta area come to Osif for help applying for federal benefits. His own experience as a miner helps build rapport and trust when having difficult conversations about the disease.

“Thirty-six years at the mine I was in dust probably 75% of the time,” said Osif.

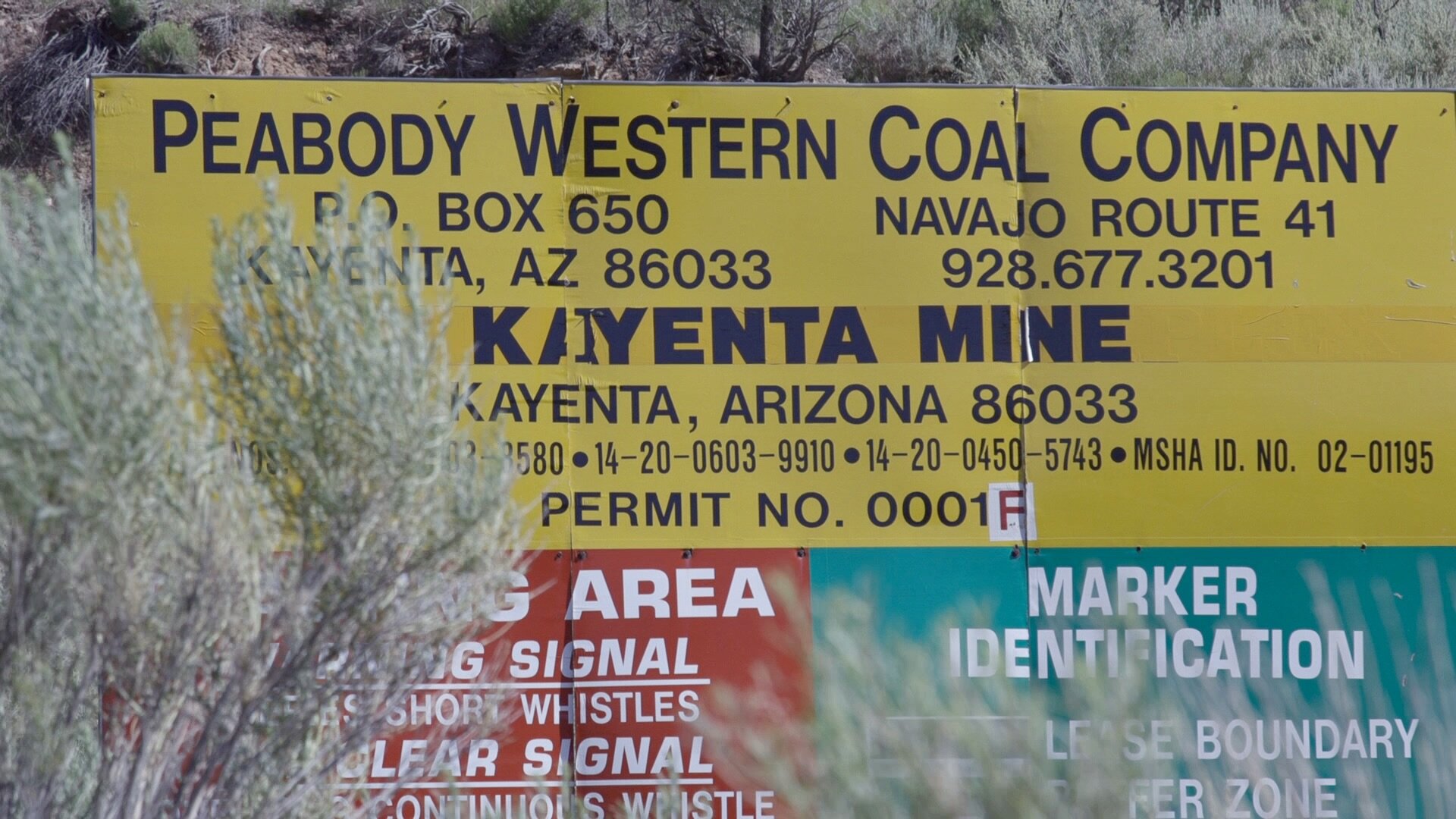

He worked at the Black Mesa mine, then at the Kayenta mine until it closed in 2019. Peabody Energy ran both mines, located near Kayenta, Arizona.

An old sign for the now closed Kayenta mine.

Photo: Zach Ben-Amots

The severity of the miners’ respiratory diseases can be influenced by adequacy of dust control regulations and use of personal protective equipment, among other factors, according to the study from National Jewish Health.

“You got dust filters in your cabs, and it should abide by law, they should be changed out daily,” Osif said.

“They're not. So of course, [there are] shortcuts that the mines take,” he said in an interview with KSJD last year.

Orphelia Thomas, who holds informational meetings for miners to learn about federal black lung benefits, said more education is needed in the region.

“They don't really realize what black lung is, especially with the term of ‘pneumoconiosis,’” said Thomas, Administrator and Community Liaison with Positive Nature Homecare.

“What I do is I try to translate that into Navajo, to fully explain to them the severity of what black lung is,” she said.

Federal benefits for miners with black lung include medical coverage for treatment of lung disease, and monthly payments to miners who are totally disabled and to families of coal miners whose death is attributed to the disease, according to the Department of Labor.

The United Mine Workers of America offers a health insurance and pension program for former miners. The federal benefits are an additional resource for miners and their families.

Oxygen and medications that open lung passages can help with symptoms of black lung, but there is no cure.

Thomas hopes miners get screened for respiratory diseases, despite reluctance to even talk about black lung.

“Many of the miners are stubborn. They don't want to know about it,” she said. "They say that if you talk about it, you'll get it,” she said.

Information about black lung being primarily in English isn’t the only challenge miners face, Osif and Thomas said. Both health officials travel scores of miles across vast distances to talk with miners and their families, and to host informational meetings.

“And I’ll tell you, it's a lot of mileage that I put on,” said Osif. "We have two vehicles here at this facility, and I've racked up, probably, over 100,000 miles already on [them].”

Osif often travels on dirt roads, through bad weather.

“We got mud, we got snow. And sometimes I don't make it to a miner for a week, you know, but that's who I am. Again, I love my job,” he said.

Black Mesa, near the clinic in Chilchinbito, Arizona.

Photo: Joshua Vorse, Rocky Mountain PBS

According to the NJH website, there are more than 5,000 current miners in Colorado, and many “ex-miners and retired miners who are at increased risk for lung disease, heart disease and hearing loss.”

National Jewish Health in Denver takes screening appointments on an ongoing basis and holds free black lung clinics with local hospitals in Craig, Montrose and Pueblo once a year.

Joshua Vorse is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. Joshuavorse@rmpbs.org

Chris Clements is a state government reporter with Wyoming Public Media and a former reporter at KSJD.

Zach Ben-Amots is a former investigative multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS.