How do you form your own town? These Coloradans are trying to find out.

SAGUACHE COUNTY, Colo. — When Colleen Bennett bought her Colorado home nearly 30 years ago, she could take her dogs on a walk and watch boats paddling across a lake. Now, in that same area, she sees dirt and tumbleweeds.

“The area was grassy and beautiful,” Bennett said. “It isn’t like that anymore.”

The people who built Bennett’s community in the 1970s set out to create a “lifetime vacation” enclave called the Baca Grande in the remote high desert of Colorado’s San Luis Valley, on the outskirts of the town of Crestone.

Bennett, 75, said she has watched many of the amenities built by the developers disappear over time. That includes the man-made lake, which has since dried up.

Still, it is the natural splendor of the community along the Sangre de Cristo mountain range that initially attracted Bennett to the Baca Grande. “It is a beautiful view,” she said. “I just had to live there. There was no choice.”

Now, it’s the kind of place where people can buy an affordable plot of land, sketch their plans, and build their own homes using alternative and eco-friendly building techniques.

And the Baca Grande remains bound to the ideas from all those years ago that property owners, not local government, could provide most of the services the community needed. Owners are members of a property owners association (POA) — it’s similar to a homeowners association, but includes those who own undeveloped lots as well. Annual dues administered by the Baca Grande POA fund everything from road maintenance, to a building department, to fire and ambulance services for thousands of members covering thousands of acres.

A home in the Grants, a largely off-grid section of the Baca Grande. (Rocky Mountain PBS)

“That’s a heavy amenity burden,” said David Graf, an attorney whose law firm represents the POA. “When you tack on the scale of what they do… that’s pretty unique.”

“It was designed to be like a little city because it was in the middle of nowhere,” said LeRoy West, vice president of the POA’s board of directors.

That volunteer board recently voted to significantly increase every property owner’s annual dues (also known as assessments) to keep up with the expenses and future needs of maintaining the expansive development, which covers at least 11,000 acres and includes more than 800 homes. But some residents are grumbling they want more from the POA.

Now, a group of residents is reigniting a recurring conversation: should the Baca Grande be a town, and not a POA? A combination of both? Or stay the way it is?

The group submitted a petition to incorporate the area in court in August. If the petition is approved by the court, registered voters who live within the proposed town’s boundaries would vote on whether to turn the area into a municipality.

The town of Baca Grande, with an estimated population exceeding 1,200, would dwarf neighboring Crestone. Proponents of the plan say the formation of a town could allow the community access to tax revenue and government grants they currently can’t tap. But the POA stands in opposition to the plan, having filed in court to intervene and dismiss the petition. They said they don't believe the potential costs and benefits of the plan have been sufficiently fleshed out by the petitioners, and argued the petition fell short of legal requirements.

Still, board members said they are not necessarily opposed to the concept of becoming a town, even though they have taken legal steps to stop the current approach.

“We want to make sure that, if that were to be the best path forward, it's done in a very deliberative and cooperative way. So that we can really know that we're not tearing the house down before we get the new house built,” West said.

“It's almost like we don't even exist”

Eddy Byerly is the kind of guy who’s always lived on the wrong side of the tracks. In the Baca Grande, he said, he’s on the wrong side of the creek.

“Crestone Creek kind of divides us, and that’s okay. We chose to be here and we’re grateful to be here,” Byerly said, leading Rocky Mountain PBS on a tour of Casita Park, the mobile home community in the Baca Grande.

He and neighbors feel Casita Park is continually getting shortchanged.

He walked through a playground with outdated metal equipment he said his grandkids find too hot to touch for much of the year. The ground is covered in gravel rocks, with prickly weeds poking through. The merry-go-round is slanted. “I’m just wondering, how safe are these edges?” he asked, running his finger across the equipment.

“We have a little water fountain here that doesn't work. So even if the kids are here, they have no place to get a sip of water,” Byerly said. “This is what Casita Park gets.”

“We’re not mad about it, we’re just wanting to do things ourselves,” he continued. He and Bennett and a group of neighbors have formed an action committee, hoping to fundraise to create spaces for the community to congregate and improve the playground. He said they want to “get people out of their little trailers and into a group where they can get to know their neighbors.”

The playground’s chain link fence was lined with mostly-bare trees, planted by Bennett and her grandson, and allowed to die years ago by POA staff who said watering them was too expensive. Those who visit the playground now are greeted with full sun and no shade.

“It seems to me like that would say a lot to people, that you're not even willing to provide shade for our children,” Bennett said.

Casita Park sits on mostly dry, flat landscape, several miles from the entrance to the other sections of the Baca Grande: the Grants, a collection of largely off-grid home sites, and the Chalets, located up in the trees.

Eddy Byerly walks through the playground in Casita Park. (Jeremy Moore/Rocky Mountain PBS)

A sign marks one entrance to the Chalets. (Rocky Mountain PBS)

The Chalets are “more like a normal sort of a subdivision,” in the words of John Rowe, a Crestone Eagle reporter who said he has covered the POA for about eight years. Some homes in the Chalets have sold for more than $600,000 in recent months. Their POA assessments are the same as those charged to the owners of undeveloped lots, and the same as those charged to owners of manufactured homes in Casita Park.

“People bought up those lots and now they have a large house with many acres around them,” Rowe said. “And they pay the same assessments as somebody with a quarter of an acre and a 500 or 600 square foot modular home.”

Bennett believes it’s unfair for Casita Park residents to pay the same amount of assessments as the other sections of the POA. She argues the POA simply doesn’t budget an equitable amount of maintenance or attention for the mobile home park, and does little to address blight in the neighborhood. At the same time, she said she and other retired, low-income neighbors will be disproportionately impacted by the increase in assessments.

“Every property owner in Casita Park is subsidizing people in the Chalets,” she said. “I'm paying my dues and nothing is being done to enhance my neighborhood, but the other neighborhoods are receiving benefits.”

Residents say at times they don’t feel like they’re part of the Baca Grande at all. Bennett said she attended board meetings for years and rarely heard the mobile home estates mentioned.

“It’s almost like we don’t even exist,” she said.

A photo donated to the Crestone Historical Museum shows the former lake in 1975. (Mary Alice Johnston)

Today, benches now overlook the area one local called “Lake No Lake.” (Rocky Mountain PBS)

The POA said it has “actively reached out and responded to Casita Park homeowner concerns” about maintenance this year. (Rocky Mountain PBS)

The community has entered a rare era of representation on the POA board of directors: Diego Martinez, a Casita Park resident, now serves as the board’s president. He joked that neighbors exerted some peer pressure on him to run for the board. He has enjoyed the challenge.

“The Chalets get most of the attention, and we’re kind of over there, the small guy,” he said. “But I think it is getting better.”

Board members said they’ve heard the complaints and restored the water budget for Casita Park in next year's budget. Martinez said he disagrees with Bennett’s contention Casita Park is paying for services it’s not receiving.

“I don't feel like I'm subsidizing anything,” Martinez said. “We can access the same amenities. I mean, they might get their roads graded a little bit more. But I think it's… in my opinion, fair.”

Martinez said he works in finance, so the association’s budget became his focus when he was elected to the POA board. He said he was concerned by the way the community had been tapping into its reserve funding (essentially, its savings accounts) to cover its everyday expenses.

“With the way we’re burning through the reserves,” he said, “I think we needed to increase the assessments to cover operations a little bit better, and then be able to fix our infrastructure, and then eventually augment the reserves so we can keep it nice for future generations.”

He said he believes the POA members should consider changing the way its assessments are charged going forward.

“My personal opinion is it'd be more equitable to do it on a tax-assessed basis,” he said. “Their house is valued by the tax, we can do something similar. There's more logistics into doing that approach. It's a little bit harder. But I think it's something we need to think about.”

Board members said such a move would require amending the association’s governing documents — which has a very high bar that would require a quorum of most of the association’s members to vote for a change at levels of participation the community doesn't usually see.

“To the extent that we amend the declaration to change the 'allocated interests' which is, among other things, the share of assessment that the unit owners pay relative to each other — it is likely that that change would require the approval of owners representing 67% of the vote,” Graf said.

“Usually the most we ever get participating in any vote is 20 to 30 percent,” West said. “The point is that we're kind of handcuffed by the situation.”

The POA recently conducted a member survey, asking for opinions on various topics including whether members would favor amending the governing documents “to allow for more equitable assessments.”

As for homeowner concerns about maintenance in Casita Park, the board said in a statement:

“In 2022 the board has actively reached out and responded to Casita Park homeowner concerns including attending Casita Park Homeowners meeting. The Board and management team recently approved a grant research and writing proposal with the goal of obtaining grant funds for a community garden area and fire-fighting well in Casita Park, among other items for the community. Additionally, the maintenance team ordered materials this fall to improve the irrigation coverage for the Casita Park greenbelt area with work scheduled to commence this winter and early spring (before spring/summer watering starts next year.) In the past, most of the blight in Casita Park was by renters. The POA sent lots of letters and made lots of phone calls to address the blight, but this has been a difficult issue to address.”

Bennett said she has heard these kinds of conversations before. She saved a newsletter from 2001, which said the board wanted to study developing a more equitable way to charge dues that would be fairer to all residents. It also mentioned that an action committee had formed in Casita Park, and the committee wanted improvements to the community’s playground.

Casita Park neighbors are working to improve the playground near the entrance to their community. (Rocky Mountain PBS)

Bennett wrote the words, “21 years ago,” on the newsletter. She is tired of waiting.

“We have never come together as a community and said, ‘This is unfair. Let's make it right,’” Bennett said. “I've seen no effort to educate people, to convince people that it's the right thing to do.”

“I think there's been a lot of things that people grumble about, and that's certainly one of the bigger ones,” Rowe said. “I don't think it's undoable, or it doesn't seem to be, with the current structure. And that's one of the reasons people would love to have a town versus this. No doubt about it.”

“A promise delivered”

“The Baca Grande brand of living… nothing has been spared to make it the best!”

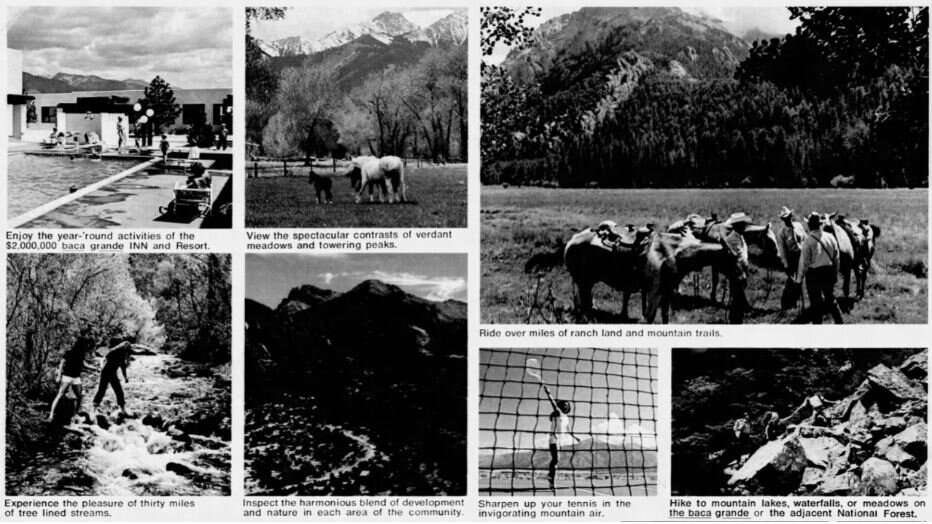

A full-page advertisement splashed photos and drawings of the Baca Grande across the pages of Lafayette, Indiana’s Journal and Courier newspaper in 1974. The pictures showed families lounging at the pool at the Baca Grande Inn and Resort, playing tennis and hiking across tree-lined creeks.

(Newspapers.com)

A postcard in the corner of the ad invited readers to clip and mail it in to learn about visiting the Baca Grande, as guests of the Arizona-Colorado Land and Cattle Company.

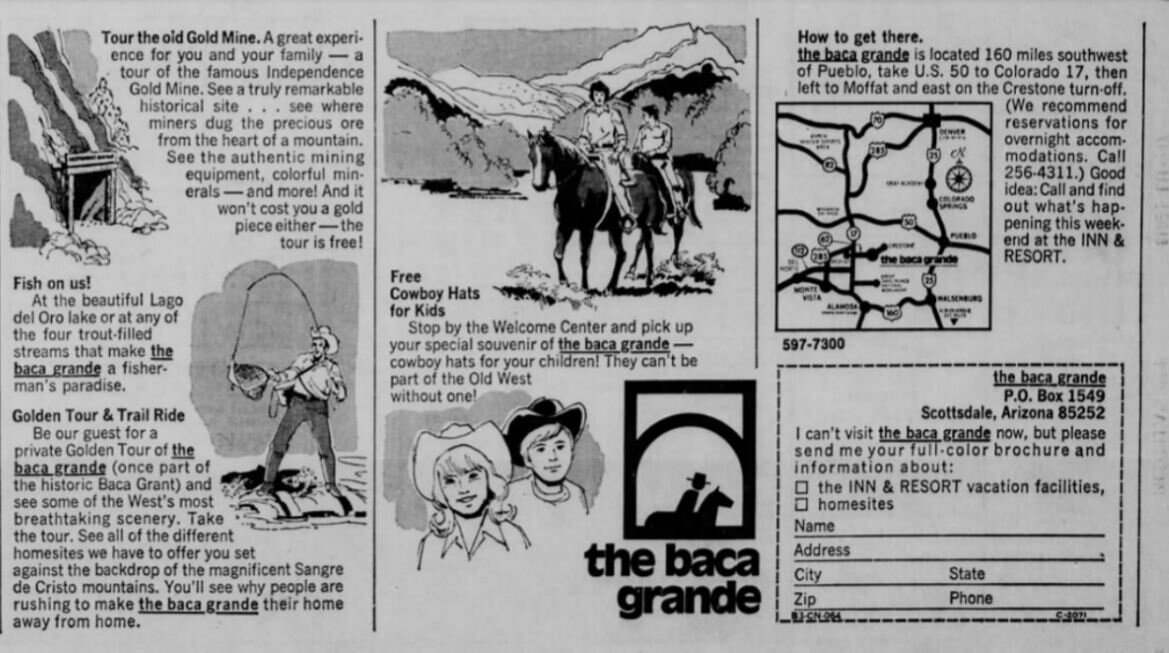

Such ads ran in newspapers in several states starting in 1971, selling plots of land in the “recreation and leisure living community.” Within a few years, prospective buyers could fly right into the Baca Grande via an airstrip and play a round of golf. The community was also reportedly marketed to members of the military as a retirement spot. Ads in the Colorado Springs paper invited folks to spend the weekend, and drop by the welcome center to pick up free cowboy hats for the kids.

(Newspapers.com)

By 1973, the company was using the “promises delivered” at the Baca Grande in ads to launch a new development in New Mexico called Angel Fire. But by 1981, the resort business was being described by business reporters as a “heavy drain” on the company’s resources. Businessman Maurice Strong took over the company, and visited the Baca Grande with his wife Hanne.

“When we flew into the Baca, I got out of the plane, looked at the mountains and said, ‘This is it,’” Hanne later wrote. “At that moment we both decided not to sell the Baca, as this would be our new home.”

After settling in, Hanne said she met a local mystic who said he had prophesied in the 1960s that a commercial real estate development would come to the area and fail, and that would open the door for a spiritual refuge to form. This vision prompted the Strongs to create the Manitou Foundation and donate large tracts of land in the Baca to spiritual centers that now line what locals call the Holy Highway.

Spiritual monuments and retreat centers attract people from all over the world to the Baca Grande. (Rocky Mountain PBS)

“We ended up with a lot of people who like to live by, and are employed by, those spiritual centers,” Rowe said of the community’s eclectic population. He counts himself and his wife among those who were initially attracted by the spiritual vibe.

“We stopped by on our way home from Taos one weekend, and there was a couple of Buddhist nuns with shaved heads walking down the street, and a few deer,” he said. “And we fell in love with the place.”

It’s the kind of community where newcomers might take up a new name. Eden Elderberry chose her name when she moved to the Baca Grande.

Eden Elderberry is part of Casita Park’s action committee. (Rocky Mountain PBS)

“A lot of people just come up with their own name when they move here. Sometimes people legally change their names, sometimes they don’t. Sometimes it’s a spiritual name,” she said. “Sometimes people just reinvent themselves.”

The POA leans into this mindset. Its website is topped with the tagline, “Meet yourself and other great people!”

Elderberry moved to the San Luis Valley from Ohio with her partner and kids. They bought a lot in Casita Park and are building a home that is partially underground, constructed with earthbags.

“We learned that they don’t really dictate what materials you use,” Elderberry said. “We were meeting people and they were telling us about their building stories and things they had done … and it was just really inspiring.”

“It ended up being a place where itinerant owner-builders could build because of the very few building regulations,” Rowe said.

The board has budgeted more than $2.8 million in operating expenses for the POA in 2023. Some of those costs include maintaining some of the remaining resort-style promises made all those years ago: for example, the association expects to spend $40,000 on the golf course for water alone in 2023.

The Baca Grande’s golf course. (Rocky Mountain PBS)

At its September meeting, the board voted to increase assessments 30%, from $493 per year to $640.90. The POA’s job is complicated by the fact that, at last estimate, 24% of its members are not in good standing – meaning, they owe money to the association.

“There's been a real effort to go back and do a fair and accurate analysis of what's happened in the last few years,” the vice president, West, said in an interview. “There's been a real effort to make a frugal but comprehensive budget based on what we need going forward, and just try to… get the house in order.”

“We have to start taking care of ourselves”

Up in the Chalets, Desiree Marceau’s straw bale house is taking shape. The chef moved from Boulder to the Baca Grande to pursue a dream of building her own home.

The area has a reputation for having loose building requirements. But Marceau’s project was wrapped up in red tape for quite some time.

Desiree Marceau gathered signatures for the petition to incorporate the Baca Grande. (Rocky Mountain PBS)

“I've never built anything in my entire lifetime, other than three layer cakes,” she laughed. “So, it's been a learning process… just to figure out how to do it, and then as a woman, to literally do it with your own two hands.”

Marceau has been the driving force behind the petition to incorporate the Baca Grande, motivated to pursue change after a three-year legal battle with the POA.

The legal fight began, Marceau admits, with her mistake: she started building on her property while her application for a building permit from the POA was still pending. Marceau represented herself in court, filing motion after motion arguing the association was not acting in good faith, and the court continually sided with the POA. At one point she agreed to a settlement, but later changed her mind. She said she didn’t have the legal knowledge or experience to understand the settlement before she agreed to it.

She appealed and filed her own lawsuit against the POA, and the association prevailed each time.

“My opinion is that they should sit down and work with the membership, say, ‘Okay, this is specifically why this isn't right, and this is how we want to see it,’ or whatever. Be more accommodating,” Marceau said. “But for certain people, for whatever reason, the intent is to set up barriers and try to just get you to give up. And I'm just not somebody who gives up easily.”

Marceau submitted self-drawn building plans to the POA six times before getting approval in the fall of 2021. She said she now owes the POA thousands in legal fees, and said she began talking with other members who believe they were sued by the POA over matters that could have been mediated before they reached the courtroom.

In response, the POA said in a statement:

"The POA generally encourages resolution of disputes through the mediation process before a matter is turned over to the POA’s attorneys. The current alternative dispute resolution process was not in place in 2018, when this matter started. (The new policy was adopted on August 4, 2021.) Second, the POA respectfully rejects Ms. Marceau’s characterization. This matter would have been resolved if Ms. Marceau had followed through on the settlement stipulation she entered into early in this process, in June 2019. Ms. Marceau had a simple and effective way to resolve this matter: follow the conditions she agreed to in the settlement stipulation to complete construction of her home. Regrettably, Ms. Marceau decided that lengthy, time-consuming, and costly litigation was a better option. Notably, Ms. Marceau has not prevailed materially at any stage of the litigation."

The POA said it incurred roughly $283,901 in legal expenses in 2021. A budget noted $122,000 of those expenses to be reimbursable (meaning that individual property owners, like Marceau, have been billed those legal fees by the POA for reimbursement). Association financial documents show nearly $430,000 in legal expenses in 2020. Marceau and other residents question whether such expenditures are justifiable when the POA’s budget is so tight that assessments are being raised.

Board members and POA staff said that criticism is misplaced, saying many of the legal fees are spent defending the POA from lawsuits, or accumulated when residents prolong cases filed by the POA by representing themselves.

Staff hired by the POA maintain roads, collect dues, and approve building applications, among other duties. (Rocky Mountain PBS)

“If you look at it, the largest amount of money the POA has spent on legal has been spent by members of the POA who are litigious coming after us and representing themselves, and then we have to pay a lawyer to defend us,” West said.

Court records show 65 cases involving the POA filed in county, state, and federal courts since 2016. (That total counts several cases for the same matter multiple times, since appeals generate new case numbers.) The POA said it was a defendant in eight of those cases, and dealt with several appeals of cases it filed. Most of the remaining cases were filed by the association against property owners who the association said did not comply with the community’s covenants, or who the POA said were delinquent in paying their assessments.

"The POA makes every effort to solve any violations through cooperation and mediation. The POA sends many notices to Owners who have not paid assessments or violated the governing documents, before matters are turned over to an attorney," the board said.

Marceau said while she was doing legal research to try to represent herself against the POA’s lawsuit, she began exploring alternatives for the community.

“I started looking for ways to basically dissolve the POA… I just basically started Googling, like, ‘How do you start your own town?’” Marceau said.

With that, Marceau said she spent about nine months crafting a petition, using the town of Foxfield’s incorporation petition as a template. She began gathering signatures while selling jams and pickles at the Baca’s unofficial farmers’ markets.

“There's an awful lot of people in the community who are not happy with the way things are. In terms of infrastructure and how things are maintained,” she said.

“As a municipality we can get federal grants to fix these problems. And no, we won't fix everything overnight… the community's been falling apart for decades. But we can start, and maybe ten years from now, things will be a lot better than they are now,” Marceau said. “We have to start taking care of ourselves.”

Lisa Cyriacks is among those who signed the petition, and has become one of the idea’s most outspoken supporters.

“I would have to say most people complain about the POA and have for quite some time,” Cyriacks said. “And I think the biggest reason is it's fairly arbitrary and capricious in how it applies the rules.”

"It's kind of always bounced back and forth between how much do we enforce things and how much do we let things play out?" she said.

Lisa Cyriacks outside her home in the Chalets. (Rocky Mountain PBS)

She has lived in the Baca Grande for close to 25 years, and has heard the conversation about becoming a town come up several times. She said she had never seen the conversation progress this far.

“I was intrigued by this idea,” she said. "This would be the first time the community could vote for or against incorporation. And I'm still really curious to see how that's going to turn out.”

“Everybody in town is talking about it”

On a Monday evening in October, a small group of Baca Grande residents crammed into the community’s library to hear more about the proposal to incorporate a new town.

Bill Cody stood watch over the group, wearing an army green vest with a “Peace Patrol” patch on the chest. He decided to attend because he heard the township meetings were drawing strong emotions.

Desiree Marceau leads a public meeting on the proposal to create a town of Baca Grande. (Rocky Mountain PBS)

“I heard that there was a little heated conversation at another meeting where Peace Patrol presence wasn't there. So I wanted to be here to make sure that everything stays peaceful and calm,” he said.

The Peace Patrol volunteer group formed to try to de-escalate community disputes, Cody said, because the Baca Grande sits about an hour away from the Saguache County Sheriff’s Office. If help is needed from law enforcement, it might not come right away.

Proponents of forming a municipality say if they become a town, that could change: the town of Baca Grande could potentially explore adding a law enforcement presence. That’s just one possibility being floated in the debate over the petition that has the whole community talking.

“I don't think the POA can pull in enough money through membership dues for some of the changes I want,” said Marcia Heusted, owner of the Coll House Bed and Breakfast in the Baca Grande. “I'm just hoping that this place can become a municipality. It's maybe the only possibility for some changes here.”

Heusted said she felt called to put down roots in the San Luis Valley nearly 30 years ago. While living on the east coast with her family, she and a friend spent a weekend traveling in New Mexico and Colorado. During the trip, she impulsively put $100 down on a lot in the Baca Grande.

“I felt I had a calling to come here, and I think many people that live here can share similar stories,” she said. “The valley is a place where they were drawn to be.”

Over the years Heusted said she attended board meetings asking if the POA can add services that would be important to her, like animal control to address the numbers of off-leash dogs roaming the community.

She says the answer was always the same: “There's no money. There's no money. There's no money,” she mimicked. But she doesn’t believe it. “There is money. We live in an abundant universe.”

“I think it's time for us to incorporate. I think it makes sense for the level of services,” Cyriacks said. ”I think that that level of self-governance is really kind of what people want. Whether or not they're ready for it is maybe another question.”

The debate over potential new forms of governance for the Baca Grande have come up several times over the years.

“I’m just wondering if there’s a little bit of magical thinking going on, that we can have all these things and they’re all paid for,” said property owner Gussie Fauntleroy.

She and a group of local residents joined a group a few years ago to strategize a resilient future for Crestone and the Baca Grande, and they met with representatives from the state’s Department of Local Affairs (DOLA). Fauntleroy came away from the conversations with the sense that it would be unlikely for a municipality to be able to replace the revenue generated by POA assessments.

At least two prior feasibility studies examined the potential impacts of different forms of governance for the Baca Grande: in 2003, a group studied incorporation of areas of the POA into its own municipality, and in 2008, the town of Crestone commissioned a study exploring the possibility of annexing the Baca Grande. Both suggested new taxes would likely be necessary for either a new town of Baca Grande or an expanded town of Crestone to cover the services funded by POA membership.

DOLA said its staff has been following the petition effort to incorporate the Baca Grande. It said due to the state’s Taxpayer Bill of Rights (also known as TABOR), voters in a new town would need to approve new tax revenue streams.

“In most cases, although taxes are structured differently, a new municipality would not be entitled to a share of an existing property tax - for example, Saguache County doesn’t share a portion of their mill levy, unless some agreement was in place; instead, the new municipality would have to pass their own mill levy. Sales tax is another example - residents would need to pass their own, they wouldn’t get an existing stream for another entity,” DOLA's Division of Local Government said in a statement.

The association maintains a network of unpaved roads in the Baca Grande. (Rocky Mountain PBS)

A new town could potentially find revenue sources through highway user tax funds, lodging taxes for the numerous short-term rental properties located throughout the Baca, and it could tap into government grants that generally are not available to community associations.

Proponents of the latest township conversation have not prepared a sample budget for the potential town of Baca Grande. They said that’s the kind of work that should be done by elected officials after voters decide if they want a town. And they said the people chosen to run a new town may choose not to replicate all of the services currently funded by the POA. Several residents said they would need some specifics on the possible costs and benefits in order to know how to vote.

“It’s difficult. Both my wife and I are going like, ‘Boy, we want more information. What's going to happen to our taxes?’” Cody said. He lives in Casita Park — an area he said gets “the short end of the stick” from the POA – but also owns two lots in other parts of the community, so he is anxious for more specifics.

“I'm paying three assessments and they just went up,” he said. “And I’m kind of wondering what the POA is doing for that.”

Valerie Herenchak calls herself a newcomer, moving to Casita Park from New Jersey after spotting a real estate listing on Zillow and marveling at a picture of the view. She said the move has been a real culture shock, in a good way – her new neighbors introduce themselves and say hello, which they never did in Jersey.

Valerie Herenchak at her home in Casita Park. (Rocky Mountain PBS)

She has since joined Casita Park’s action committee, advocating for more services and maintenance for her community. But she’s still not sure where she stands on the township idea.

“I think changes need to be made. And if the POA can't restructure the bylaws to make it more equitable, a lot of people think that it needs to be dissolved completely,” she said. “But I'm not sure we'd be trading [the POA] for something better. I mean, municipalities still have the same expenses.”

Bennett signed the petition, and said she sees this proposal as a logical way to reduce the inequity in Casita Park she has long been able to convince anyone to address.

“It's so easy. Taxation is fair,” she said. The large homes she feels she’s subsidizing will be taxed more, while she anticipates she’d be taxed very little. “It’s been 25 years for me of being ignored and being dismissed and being asked to pay for things for other people.”

While many of the Baca’s residents are already digging into the debate, if the POA has its way, the current matter will not come up for a vote.

The association argued in court the petition should be dismissed. The POA said in court filings that because the association owns three undivided parcels of more than 40 acres of the Baca Grande, its permission is required by state law in order to incorporate the area, but the petitioners did not get that blessing before they filed in court. The POA has also argued the petitioners have not submitted a sufficient map to show the boundaries of a potential town.

The POA board has posted the court documents on the association’s website to keep homeowners informed, answered Frequently Asked Questions about the plan, and weighed in on the proposal with a statement to members.

“These Motions should not be construed to mean we are against different ideas or even the thought of exploring various paths forward; however, our responsibility is to protect the property values of our Members and preserve the desirability of the Baca Grande. We feel the petition, as filed, and currently pursued, poses significant risks to our collective future,” they wrote.

If a town is created, the POA would still exist. Dissolving it, and transferring its assets, would require votes of POA membership. Because a town and POA may have to coexist, board members said they would need to ensure any incorporation plan protects the interests of property owners.

“It's not a bad idea. We’re totally open to the conversation. It needs to be done in a careful, deliberate, cooperative way,” West said.

“I think it would have been better if they would have agreed to a conversation,” Cyriacks said of the POA board. “I mean, they're spending money on attorneys on the one hand, which are not cheap, and then complaining that they don't have enough money and that's why they're having to raise the assessments by 30 percent.”

The Baca Grande provides fire and ambulance service for its members because of its remote nature. (Rocky Mountain PBS)

“I think the thing that's the most appealing about [becoming a town] is that it would be more of a democracy,” Elderberry said. “With the quorum situation and the way that the system is set up, I just don't feel like the changes that people are wanting are going to be able to be made.”

The court’s decision on whether the issue should go to a vote is likely at least six weeks away, with both sides set to trade legal filings in the weeks ahead. Marceau said supporters are using their personal funds for the effort and are fundraising on GoFundMe.

Supporters of the petition have created a website and hosted public meetings to answer questions about the process. They said there are limits to how many specifics they can gather in a citizen-funded effort. But their volunteer members are trying to put together as many details about potential revenue streams as possible, so residents will be informed should the issue go to a vote.

“It's a simple majority. So if 20 people show up and 11 people say yes, then we're a town,” Marceau said. “So the goal really is to just keep reaching to the people who support it, number one, and try to get other people off the fence and then hope that they're the ones who show up and vote.”

“If for some reason that doesn't go through, we would just try it again in a year. I mean, it's not like I'm going to give up on it,” she said.

“I just think everybody here on both sides of that question are all good hearted,” Rowe said. “I really think that the people who are presenting the town think it's the best option for us. And people who think that we just can't get that to happen very well at all, they're also well-intentioned. There's no big, mean, bad guy.”

Supporters of the new town said they believe the POA has been more transparent and responsive to member concerns since their petition was filed. Whether or not the idea prevails, they believe they’ve opened up a conversation about improving the community.

Casita Park residents pulled up dead trees outside their playground this week. (Eden Elderberry)

In Casita Park, residents have taken a long-standing source of frustration into their own hands. This week, they pulled up the dead trees lining the front of the playground planted by Bennett years ago, so that new trees can eventually grow in their place.

The action committee, with POA support, secured a county grant to replace the irrigation system for the area and to provide some shade for the park.

“I really do think a lot of us just want to build bridges and we want to be active with the POA or the town, or whatever it is that happens,” Elderberry said. “I think there are a lot of positive things that could happen out of this.”

UPDATE: The court granted the POA's motion to dismiss the petition to form a new town. The petitioners said they plan to try again, and began gathering signatures for a new petition they said will address the problems with their original filing.

Brittany Freeman is the executive producer of investigative journalism at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at brittanyfreeman@rmpbs.org.

Jeremy Moore is the senior multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach him at jeremymoore@rmpbs.org.