Native Lens: A journey for community stories amidst protests and pandemic

With heavy hearts in the Wakpa Ipaks’an, the past few months have been difficult in the community of the Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe of South Dakota. After a great loss of their relatives to Covid-19, the hearts of the tribal members were heavy with grief and fear. Looking to create some good healthy memories again within the community, organizer Dustin Beaulieu, a few colleagues and the Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribal Council began planning a Rejuvenation Round Dance, which had not been done in Flandreau in over 40 years.

This is usually a time to interact with one another closely but due to Covid-19 there were strict guidelines that had to be followed which presented a unique challenge in organizing the Rejuvenation Round Dance. The Round Dance is a way for the Indigenous communities to heal and uplift each other through song and dance. In the midst of this pandemic the tribal members for at least a few hours were able to smile, laugh and be together as they had done for so many winters past.

Native Lens contributor Jonathan Kelley wrote this personal account of his journey to capturing community stories.

Growing up in Oakland, California, I was exposed to many different cultures and languages. Oakland has been at the center of many of our revolutions for equality. Think about the Occupation of Alcatraz, the Chicano movement in the Bay Area, and the Black Panther Party — all of these important movements had a home base in Oakland. I feel very proud to call Oakland home.

My mother raised me to speak up about the things I saw in my community that weren’t right. As an Afro-Indigenous youth (African Diaspora and Muskogee Creek) I always wanted to know more about people and subjects that arose my curiosity, so I began developing the skill of researching. I would write book reports during my summer breaks about topics I was curious about. I would then stand in front of my family and read my findings out loud and answer any questions they may have had. I was curious about my Indigenous relatives, because I never had a connection to my African ancestors’ homelands. Slavery had wiped away those memories. I tried to feel what Indigenous people felt about being removed from their homelands, often times forcibly. I was also hurt that I never had a story to tell about my own origination story. Deep inside these questions would shape my thoughts and became a big reason why I picked up my camera at 10 years old and began documenting the events that were happening all around me. I have always been a protector and a fighter for those who have something to say but may not have the courage to say it. That doesn’t mean I am their speaker or their savior, but it does mean I am willing to be a vessel of expression for those who feel voiceless or powerless. I have to thank my parents, my community and Oakland for the courage I have to stand on the front lines today and document and archive our history.

Summer 2018: A huge shift begins to happen. My mother was diagnosed with Stage 4 cancer. Driving from Denver to Orlando several times during the year to visit her as she was going through chemotherapy treatments left me with a lot of time to think about my own life. There never seems to be the perfect time to take a leap of faith. But in the summer of 2019, after my mother made her journey back to the Spirit world, that call came in loud and clear. I remember my mom’s last words to me: “Son, don’t use up all your life doing things you don’t really feel passionate about. If you want to do something, go do it, and know there will always be obstacles and risks involved — but if you love what you do, then it will all take care of itself.”

I knew I was ready for a change. The time had come to retire from my corporate job at Wells Fargo. I dreamed of traveling the country and the world with my wife and creative partner Letishia. We wanted to tell stories from our own perspectives using still and motion pictures. And we wanted to see our niece Tishara play her senior season of high school basketball in Flandreau, South Dakota. Letishia is Diné and grew up on the Navajo Reservation in Northern Arizona before going to college at the University of Arizona and Pima Community College in Tucson, Arizona, We talked about traveling to South Dakota to be closer to Letishia’s family especially after my mother passed away. Letishia left the Navajo reservation when she was 18 and really hadn’t been around her family much during her own personal explorations that included stops in Phoenix, Scottsdale, and Denver. Returning to South Dakota would be a great opportunity to have some much needed time with her brother, mother, and our other niece and nephew.

As Tishara’s basketball season progressed, everything came down to the last game of the season — and potentially the last game of her high school career. Tishara hit seven three-pointers that night, and the girls won the game and a trip back to the state basketball tournament in Rapid City. Then the Covid-19 Pandemic changed the way we’d live our lives for the rest of the foreseeable future. The girl’s state basketball tournament was cancelled and cities and states around the country began to implement stay-at-home orders, effectively shutting down most or all of our daily activities.

Then I saw the video of George Floyd being murdered by four Minneapolis Police officers. After deciding to stay in South Dakota due to the rising Covid-19 cases in Colorado, I immediately wanted to make the three-hour drive to Minneapolis. Debating if I should go, I asked Letishia if she would make the trip with me as an activist first and foremost. The national media’s coverage of the uprising in Minneapolis pushed me to archive and document what was happening from our own viewpoint of being on the front lines of the social justice uprising we were all witnessing in front of us. Often times people of color are not given the space to tell our own stories, and I felt in this moment I had to show the world images that caused us to look at this movement from a different emotional perspective.

We traveled to Keystone, South Dakota, on July 3 to document the Lakota’s protests of President Trump and South Dakota Governor Noem’s 4th of July celebration on Lakota Lands without the consultation or permission of the Lakota Tribal Council. We were blessed with an amazing interview with community leader Chase Iron Eyes of the Lakota People’s Law Project. Chase’s seven-minute interview was, among many things, a powerful message about solidarity, the land back movement, community, and reparations. His words matched the intensity, energy and courage I witnessed throughout the day. The thoughtful strategy and execution by about 200 Black Hills Land Defenders led by Nick Tilsen of NDN Collective was effective in delaying the President’s event while elevating the call for Indigenous lands to be returned to their original stewards. I left the Black Hills even more inspired than when I had arrived.

When I returned to Flandreau, I wanted to know more about the Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe. I found out about a Rejuvenation Round Dance taking place in Flandreau which was organized by Dakota Language Director Dustin Beaulieu, the Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe, and other community members. I reached out to Dustin to see if it would be okay to photograph and record parts of the round dance that were not sacred. After a phone conversation Dustin agreed to allow me to document the round dance and asked me if I would in fact be the photographer for the event as the photographer they had couldn’t make it. Dustin wanted to archive this round dance as a part of the tribe’s history during the pandemic. I was honored to be able to do something like this. The significance of this moment was also heightened because Flandreau hadn’t had a round dance in over 40 years.

This was something the Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribal members had been longing for, even if masks and social distancing were required. The people longed to feel the healing from the sounds of the drums and the round dance singers. We sat down with Dustin after the round dance and talked about the reasons why he felt the round dance was needed during this time. Dustin explained that there had been a lot of loss during the pandemic. He felt the community’s collective pain and wanted to think of a way to do something safely that could bring some healing and joy to the people.

I realized what we captured that day at the round dance will be a part of the history of the Flandreau Santee Sioux and the town of Flandreau forever. There is great importance in People of Color archiving and documenting our moments in the history of America from our own authentic voices and perspectives.

There is no one that is better equipped to tell the stories of your community than you. You can’t wait for someone else to do what you feel you’ve been called to do or to tell the stories you don’t see being told about your community. To me that is one of the most important lessons I’ve learned in 2020 and something that has forever changed me as a photographer, storyteller and filmmaker.

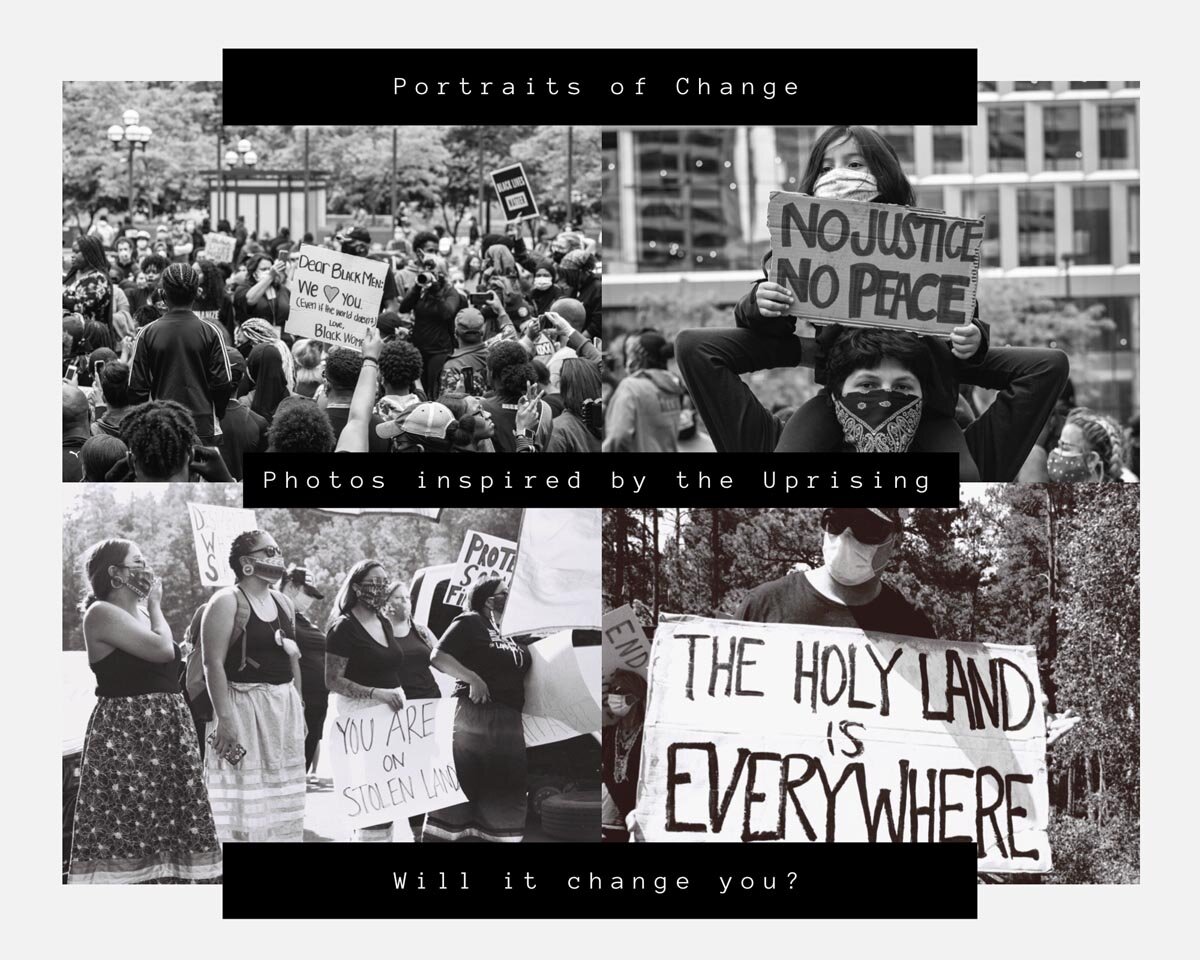

We decided to stay in Flandreau, South Dakota, for the time being because of Covid-19 and the restrictions of traveling during this pandemic. We had a few projects in place in Colorado that have been postponed until 2021. We’ve taken this time to work on our first solo exhibition which will be showcased in the fall of 2021 in Denver called “Portraits of Change.” Portraits of Change is a collection of still and motion pictures that were inspired by this summer’s uprisings in Minneapolis and Keystone, South Dakota.

The summer of 2020 truly allowed us to find our artistic voices and we will continue to tell the stories that often go untold and inspire us to be the change we wish to see in the world.

As a creative husband/wife duo Jonathan Kelley (Afro Indigenous) and Letishia Kelley (Diné), are storytellers that aspire to create narratives that evokes awareness, unity, and collaboration. As lifelong learners, researchers and students of the visual arts, the emotional connections to their motives lead them to capture the most intimate moments. The themes that they choose come from a place of intuition and an impulsive desire to partake in the unique stories that unfold around them. The beauty and the essence of their body of work is truly based on the unique characters and creative storylines from an internal point of view. As Filmmakers, Music Producers, Editors, Photographers, Creative Writers, and Community Activists they use complimentary perspectives which produce thought-provoking, candid, dramatic and authentic forms of self-expression.

Letishia Lynn Kelley (Diné) was born and resided on the Navajo Nation Reservation in Northern Arizona until she was 18 years of age. She attended the University of Arizona and Pima Community College in Tucson, AZ where she studied Psychology and Native American Studies. Having a long affinity for film particularly Star Wars and Documentaries, Letishia decided to pursue Photography and Filmmaking along with her creative partner Jonathan Kelley. As an Indigenous Leader, Letishia is the Director, Editor, Writer, and CEO of THINC INC. which is a Creative Media Agency Co-Founded with her husband Jonathan Kelley. THINC is acronym for Thinking Helps Inspire New Creations. Letishia is currently working on her debut Photo Archival Collection and Short Narrative film both titled “Portraits of Change” which will be on exhibit in the Fall of 2021 in Denver, Colorado.

Jonathan Kelley (Afro-Indigenous) was born and raised in Oakland, CA. He spent some of his youth living in Orlando, FL after his parents divorced at a very young age. He graduated from Johnson and Wales University (Denver, Colorado) with a degree in Business Administration in 2002 and in 2016 he returned to Denver, CO with his creative partner Letishia Kelley to be a contributor to the blossoming art, cultural, innovative and creative community in Colorado. In 2017 he graduated from the Colorado Business Committee for the Arts (CBCA) Leaderships Arts Program. Upon graduation he served on the Board of Directors for PlatteForum, a youth arts organization, in Denver for 2 years. Jonathan is a Community Activist, Photographer, Filmmaker, Entrepreneur, Leader, Nature Lover, Music Producer and Creative Writer. Jonathan is currently working on his debut Photo Archival Collection and Short Narrative film both titled “Portraits of Change” which will be on exhibit in the Fall of 2021 in Denver, Colorado.